Founders talk frankly about being sidelined in recent competitions as succession plans foundered

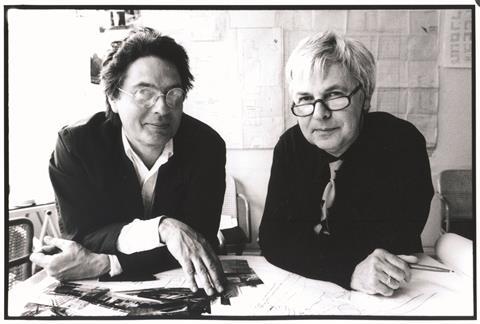

The founders of Dixon Jones have spoken of their sadness as they are forced to wind up the influential practice they established 30 years ago.

Jeremy Dixon and Edward Jones were warned by their accountant they faced a “mountain of debt” if they did not close the firm which was responsible for some of the UK’s most prestigious projects including the transformation of the Royal Opera House, the National Portrait Gallery and the replacement of cars by fountains in Somerset House’s courtyard.

Half a dozen people have been made redundant, while a further five are continuing to work on the practice’s ongoing projects after being taken on by those schemes’ contractors or clients.

The practice had shrunk from a high of 30-plus staff as work slipped away in recent years. It closed at the end of September and was placed into liquidation last week, with the founders deciding to close the practice rather than seek a buyer. Almost all of their debts have been settled, they told Building Design.

The pair, both now 81, admit they failed to successfully plan for their succession and as a result were increasingly sidelined when they bid for work.

“As it became evident we were a certain age and we weren’t getting a succession in place, we were losing the projects we might have got previously. We weren’t getting on lists,” said Dixon.

“I interpret that as clients being put off by not having a viable practice that could look after projects that might last 10 years. It was rather depressing.”

While not disputing the logic, he said today’s increasingly professionalised competition system would have been a barrier to their fledgling practice back in 1989 when they set up on the back of Jones winning Mississauga City Hall near Toronto and Dixon winning the Royal Opera House in Covent Garden with Bill Jack of BDP.

“We did the Opera House entry from my bedroom and we’d have never got through the first screening at all today,” said Dixon. “We wouldn’t have stood a chance.”

Their focus was always on pursuing projects they loved rather than on the business side of the practice, said Jones, adding: “I offer that as a word of caution to the next generation but at the same time I have no regrets.”

But he added: “We are going into liquidation, with all the consequences that has, and of course it’s sad to be told you are no longer working, because work is life.”

Jones said they hoped to continue working as consultants.

“There’s still lead in the pencil,” he said. “Jeremy and I are both still designers and we will continue to occupy ourselves in different ways – but not as Dixon Jones.

“We are architects and architects don’t retire as chartered accounts might.”

Their ongoing projects are: public realm improvements to College Green outside Trinity College in Dublin, which is about to go in for a second attempt at planning; the conversion of a whole terrace in Knightsbridge into luxury duplex apartments over commercial and retail space; a workplace scheme in Marylebone; a marketing suite in Edinburgh; and the Olympic Steps at Wembley Stadium.

Dixon and Jones, who met at the AA, established their practice unusually late in life – they were in their 50s. They credit that long history of practising separately for the lack of a house style and for their varied output, “from high tech to completely contextual… though there are repeating motifs”.

This was a strength intellectually, they said, but ultimately made it harder for the practice to survive the loss of its founders, who still do all their work by hand.

“This diversity of positions makes it much more difficult for young people to take over,” said Dixon. “When we came to suggest a succession with the younger people in the office it was at a time when it wasn’t a very attractive-looking proposition. Perhaps we didn’t start early enough.”

He added: “They are a wonderful group of people. One of the great sadnesses of ending the practice is to lose that sense of being connected, working with people who make an artistry of working with the computer. That’s quite a major loss and we both feel it.”

>> Architects on film: Dixon Jones talk to Building Design about projects, influences and unconventional clients

>> Building Study: Kings Place

>> Building Study: Quadrant Three

Dixon Jones: A partial history

Ed Jones and Jeremy Dixon met at the AA in the early 1960s where they were interested in “institutions and housing” and, working mostly separately, did a string of interesting social housing projects before Thatcher brought that to an end.

“We graduated into a world that needed to rebuild cities after the Second World War,” said Dixon, noting that Harold Wilson’s support for a project like Derek Walker’s Milton Keynes – which they worked on – is almost unthinkable now.

“It’s totally unimaginable that people in their 20s or 30s might have a brief to build 1,000 houses. That doesn’t happen any more.” Thatcher’s refusal to support local authorities was a “very bleak moment for architects,” he said.

Then they rode a wave of lottery funding, with celebrated projects at the Royal Opera House, National Gallery, National Portrait Gallery and Somerset House.

When that ran dry they say they were lucky to land Kings Place for Peter Millican, a commercial office building on the edge of King’s Cross with an arts centre in the basement. They credit that with helping them make the transition into commercial projects.

Other significant projects include Oxford’s Said Business School – and other university work at Cambridge, Aberdeen and Portsmouth – the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds, Exhibition Road in South Kensington and Quadrant Three in Piccadilly.

Royal Opera House

It was not for 16 years after Dixon Jones was set up that they completed their founding project, the Royal Opera House expansion.

“London is ever cautious and puts up lots of hurdles,” said Dixon. He described the tribulations of the on-off project as worthy of an opera itself. The original scheme was to be funded by commercial spaces. But when opera house director Jeremy Isaacs was giving prime minister John Major a backstage tour he let slip that a National Lottery to fund major arts projects was about to be announced. The architects were told to quickly redraft a 100% cultural scheme, allowing them to be at the front of the queue for cash a few months later. This proved critical because the lottery was soon refocused on more populist projects.

People

In their Zoom interview with Building Design they heap praise on the clients who made some of their key projects happen, including Isaacs at the ROH, Charles Saumarez Smith at the National Portrait Gallery, Millican at Kings Place “who gave a concert hall to the city”, Daniel Moylan on Exhibition Road, and Duncan Wilson at Somerset House – “who was prepared to walk down the road and ask the bank for £1m for the fountains”.

Between them they have taught five Gold Medal winners including Grafton, O’Donnell & Tuomey and David Chipperfield, as well as Jamie Fobert and Peter St John. Jones describes their network of former students, cherished colleagues and clients as “an ongoing society beyond the confines of the practice”.

They are also stimulated by the changes others make to their buildings - such as Stanton Williams at Covent Garden and Jamie Fobert at the National Portrait Gallery. Friends ask if such interference distresses them, says Dixon, but “you see yourself as part of a cumulative procedure” of change in the city. Indeed they recently went in to Fobert’s office to lead crits on his competition-winning proposals to reorient the NPG, which they support.

No comments yet