Architecture student Elliot Robbie argues that by dismissing traditional design, architectural education risks alienating the very public it claims to serve – excluding large sections of society from shaping and identifying with the built environment

There is a widespread belief within architectural education that traditional architecture is elitist and unwelcoming to people from less affluent or diverse backgrounds. My own experience as a student has led me to believe the exact opposite is often true.

Traditional buildings are often the ones people feel most comfortable in, yet in schools of architecture, a preference for traditional design is regularly treated as outdated or even suspect. This attitude not only limits creative freedom but may itself be a barrier to diversity in the profession.

If we asked the general public what kind of architecture contributes to the marginalisation of less affluent communities, many would probably point to the concrete high-rises of the 1960s or the deeply flawed New Town experiments in places like Cumbernauld. Yet the architectural establishment persists in the view that modernist ‘innovation’ is the best way to create inclusive and popular places for people to live and work.

But the reality is that for most ordinary people, that is, those who aren’t architects, modernism is simply a style, not an all-encompassing worldview from which all designers should source their intentions. Those outside the profession might be forgiven for wondering why this single historical movement still holds such dominance within architectural culture.

As Gavin Stamp’s Interwar: British Architecture 1919–39 so brilliantly showed, there was nothing inevitable about the rise or post-war dominance of modernism. British architecture between the wars, as before it, was eclectic, stylistically diverse and often playful.

When we think of welcoming, enduring architecture that has stood the test of time, it is places like the Boundary Estate in Shoreditch, a parish church’s bell tower, or one of the many Carnegie libraries that come to mind. These are buildings rooted in civic purpose and local identity, designed with care and proportion, and still cherished by the communities they serve.

Their continued popularity suggests that traditional architecture and urbanism, far from being elitist or exclusionary, often provides the familiarity and dignity that people value most. Yet last semester, in a tutor meeting, I was taken aback when my design tutor warned against designing my library in a Victorian style, claiming it would intimidate poorer residents and exclude them from a space meant for them.

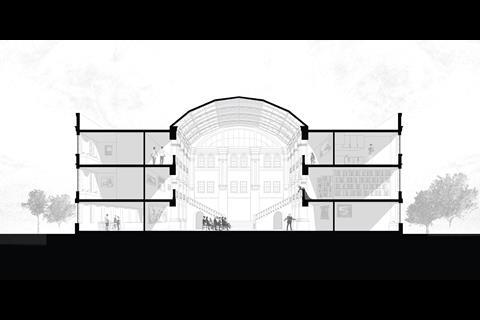

The project in question is a community library for the impoverished area of Vauxhall in North Liverpool. It is located behind Stanley Dock, home to the fifth-largest brick building in the world, Tobacco Warehouse.

My initial sketch for the front façade adopted a similar style to Tobacco Warehouse, particularly in its brickwork, repetition of elements, and ornamentation. Despite this attention to the social and historical context, my early idea was met with a prejudiced unease from my tutor.

Upon receipt of this feedback, I set out to justify my design intentions, which led me to a 2018 paper by Policy Exchange, Building More, Building Beautiful, which concluded: “Poorer communities in particular are keen to see more traditional design and style which is more likely to fit in with existing buildings.”

The next time I saw my tutor was at my mid-term review and, armed with this research, I presented my project ideas, argued my case, and backed it up with quotes from the paper. Thankfully, my tutor didn’t argue about the style further, conceding that we could spend a long time debating philosophy.

My external reviewer gave guarded support, warning me that it would take ten times as much effort to make a traditional design work. The more concrete backing was helpful in allowing me to continue, but it felt unfair that I was the only one who was forced to explain my stylistic preferences.

Thankfully, after the review, my tutor encouraged me to go the whole mile, even prompting the addition of a grand staircase in the main hall. At the end of term review, the external reviewer who had cautioned me at my mid-term gave encouraging feedback and praised the design I produced, which I was so pleased to hear.

However, on a previous design project, an argumentative review highlighted the more common bias against traditional architecture. My proposal for a Peak District visitor centre was a compromise between my desire to bring in traditional elements and my tutors’ contemporary leanings. My external reviewer and I did not see eye to eye, to say the least.

Hailing NOMA 2 by the Bjarke Ingels Group as the pinnacle of traditionally inspired design, he criticised my proposal for the more obvious references to local style, such as the limestone quoins. Pointing out my disproportionately elongated windows, he said, “If that’s your style, that’s fine, but you need to do it properly.”

Unfortunately, finding the time to learn the elements of traditional design is difficult with an already heavy schedule. Even though I knew what I wanted to do, it was difficult to make space and find guidance within the week to be able to do so. We are, however, made to learn Rhino (with Grasshopper) and Revit, which are geared towards contemporary design trends, in spite of the diverse philosophies and preferences among the cohort.

Having started working at ADAM architecture, I have learned a great deal about classical design, from proportions to construction techniques. In a seminar by director George Saumarez-Smith, the depths of the classical design tradition were explored, beyond the aesthetics and underlying geometries of the style.

Classicism is so broad and there are so many variations, yet they are underpinned by certain characteristics and principles. The gothic style similarly has certain characteristics, but there are recognised vernacular distinctions such as the English Gothic. This speaks to traditional architecture’s ability to adapt, be reinterpreted, and evolve in specific social, historical, and geographical contexts.

Change is needed in education in order to equitably equip future architects, regardless of their stylistic preferences

Contrarily, modernism is founded on being new, universal, and seeing the past as “unclean”, “unevolved”, “disgusting”, etc. Since then, new movements have looked back with justifiably critical eyes on modernism, but it seems we are in a cycle of lurching from one new contemporary design philosophy to the next, each of which have had their flaws revealed over time.

The contemporary architect also faces what is called the “design disconnect”: most people don’t like adventurous and shocking buildings, and much prefer the familiar, sturdy buildings that fit into existing contexts. Traditional design, when implemented beyond superficial design choices, is a sound way forward to creating beautiful and sustainable buildings and places.

Modern architecture often photographs beautifully on its opening day, all sharp lines and pristine surfaces. Yet poor detailing, the extensive use of mastics, and reliance on lightweight components that weather badly mean many such buildings age quickly and are difficult to maintain. Much of the modernist project was underpinned by a throwaway, consumerist economic model, with buildings designed to last only a few decades before being replaced. Conceived in defiance of local climate, materials, and energy constraints, this approach is, at its core, both materially and socially unsustainable.

Change is needed in education in order to equitably equip future architects, regardless of their stylistic preferences. I think it would be fairer if optional modules were offered to teach different skills suited to different styles. As it stands, the system is heavily biased towards contemporary design trends and should be diversified.

Schools of architecture also need to promote a wider range of successful architecture. Sustainability certifications such as BREEAM are, rightly, given plenty of attention in our technical modules. But most students dismiss the success of sustainable town projects like Poundbury, which is widely derided despite being popular, walkable and a genuinely sustainable place that won’t need to be demolished and rebuilt in the next few decades.

If we are serious about designing and building truly sustainable communities, we must be willing to look back to the past to learn lessons of longevity, beauty, and place-making – and to implement insights meaningfully. That means engaging with popular and diverse tastes and traditions, and re-engaging with the full depth and richness of architectural history – not just in Britain, but across the world.

>> Also read: Why we teach classical design

>> Also read: Beauty is in the eye of the community

>> Also read: New towns. Old wisdom?

Postscript

Elliot Robbie is a third year architecture student at Loughborough University, currently on placement at ADAM architecture.

9 Readers' comments