Why has Coventry turned its back on its rich 20th century architectural heritage, asks Joe Holyoak

What role should we expect town planning and architecture to play in a city’s year-long celebration of being the UK City of Culture? Given that planning and architecture are themselves cultural products, and the physical form inside which culture of all varieties – high and low, permanent and transitory – is generated, we might expect them to be given a high profile.

The third UK City of Culture, Coventry, completed its year at the end of May. Before the Second World War, Coventry was famous for its mediaeval architecture. It had a fine cathedral, several churches of great quality, and a wealth of other domestic, commercial and institutional buildings from the Middle Ages. These reflected the time when Coventry was the fourth most populous and the fourth wealthiest city in England.

After the war, that urban fabric was in ruins: in particular as a consequence of the terrible Luftwaffe raid in November 1940, which destroyed much of the city centre. Donald Gibson, appointed in 1938 as the city’s first Chief Architect and Planning Officer at the age of 29, reshaped the city centre with a pioneering plan (which he actually made before the Luftwaffe enabled it).

The Upper and Lower Precincts, generously-scaled traffic-free spaces, are actually on a Beaux-Arts plan: axial and symmetrical, the long axis aligned on the cathedral spire. They radically redefined what a modern, postwar city centre could look like. Gibson’s distinguished work, and that of his successor from 1955 Arthur Ling, defines the modern identity of the city.

But look for a recognition of this in the City of Culture publicity, and you looked in vain. Its organisation was separate from the city council, but both appear determined to ignore Coventry’s pioneering 20th century architecture and, in the council’s case, to dismantle it. Gibson’s plan was first carelessly disrupted by the construction in 1990 of an indoor shopping mall blocking the cathedral spire axis. Since then, the Upper Precinct has been mutilated by the removal of original canopies, balustrades and staircases.

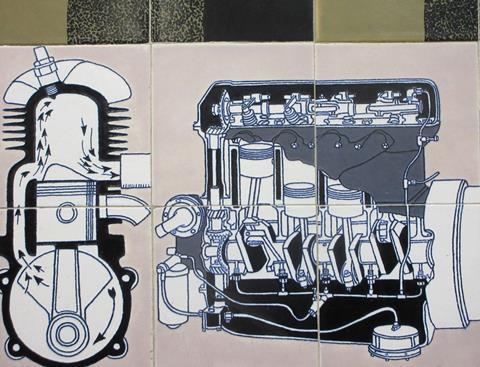

There are currently plans to remove and redevelop parts of the shopping centre added to Gibson’s precinct by Ling, and his successor Terence Gregory. One part is Bull Yard, an urbane pedestrian square containing the Three Tuns pub, which has an extraordinary 1966 Grade II listed concrete relief by the artist William Mitchell. This is one of several works of public art integrated into the shopping centre. They include the wonderful 1958 ceramic mural by Gordon Cullen in the Lower Precinct, depicting the history of Coventry, already damaged during an earlier relocation.

Another threatened casualty of this redevelopment is City Arcade, an intimately-scaled mall which is home to a number of small independent retailers, plus a theatre in an ex-fish and chips shop. Its disappearance would not only be a loss of architectural fabric, but would also represent a loss of economic and social diversity from the city centre.

Beyond the cathedral stands the empty and unused Grade II listed Central Baths, described by Historic England as “among the most ambitious baths built anywhere in Britain in the short period between 1960 and 1966 when large swimming complexes were encouraged”. Does the city value this marvellous civic building? It is currently advertised as for sale or to let, together with the adjacent Dry Sports Centre (known popularly as The Elephant), also empty and unused. Both buildings were on the Twentieth Century Society’s Buildings at Risk schedule, and Bull Yard is on the current schedule.

The worst case of neglect is the Civic Centre 2 building. This is one of four buildings which enclosed a public courtyard, built 1957-59 under Ling’s leadership. in 2013 they were sold by the city council to Coventry University. All four were proposed for listing, but only one was listed: the other three were demolished by the university.

Civic Centre 2 was an elegant three-storey building that contained the planners and architects: its ground floor opened up by pilotis, enclosing a public exhibition space, the upper floors having glazed curtain walling. The university’s architects, Broadway Malyan, gained permission to demolish one quarter of the listed building, and to utterly transform the appearance of the remainder. The 20th Century Society describes the changes as “nothing short of appalling”.

To add insult to injury, the university boldly tells us on the surrounding hoardings that “We are protecting our valuable heritage as we deliver a new landmark building for Coventry”.

By contrast, here is a reminder of what can and should be done with Coventry’s 20th century architecture. An intelligent and enterprising developer, Ian Harrabin, who heads Complex Development Projects, bought the redundant 1957 Coventry Telegraph newspaper building, opposite the Belgrade Theatre. With his architects Hadfield Cawkwell Davidson, he has successfully converted it into the Telegraph Hotel, retaining its distinctive Festival of Britain character in both its overall form and in its material detail. If only the city council and the university could display the same respect and care…

Postscript

Joe Holyoak is an architect and urban designer practising in Birmingham.

1 Readers' comment