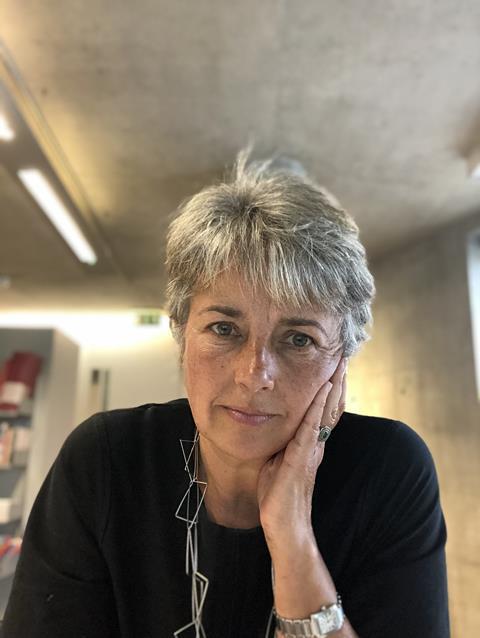

In an exclusive interview, Allies & Morrison managing partner Jo Bacon explains why she is standing to be RIBA’s next president and outlines her priorities for the institute if elected

“Now’s not the time to flip flop about with changes of direction,” says Jo Bacon, managing partner at Allies & Morrison and a candidate to be RIBA’s next president. “We need to keep going with the very good stuff that’s happening. And it’s essential to the life of the RIBA as a sustainable institute.”

Bacon is the most high profile of the three candidates to be the institute’s next president, but she very much has her feet on the ground. The RIBA was until recently running a deficit of some £9m a year. At a time when many members are calling for radical change at the 188-year-old institute, her priority is ensuring that it remains solvent.

A senior RIBA figure told Building Design last month that the next president will have a “huge job on their hands” in terms of balancing the books. Current president Simon Allford has already “shouldered much of the burden”, Bacon says, but there is still much to do. “The next president will need to hit the ground running to ensure that all these initiatives are not completely lost.”

She is this election’s continuity candidate, and unashamedly so. Bacon is on RIBA’s board as the member responsible for culture and events, and is also an elected member of its council. She has worked closely with the institute’s top team over the past few years and says in her manifesto that she “supports continuity of the good work of past presidents”.

She also applauds Allford’s House of Architecture vision, which aims to cement RIBA’s position as the cultural hub of the profession by opening up its collections and archives to members, and holding more events. Her planned direction of travel is to progress this initiative, which she says is needed to “maintain momentum and to bring the RIBA toward a sustainable and engaging future”.

>> Also read: Riba presidential candidates unveil manifestos as voting opens

>> Also read: Interview with Sumita Singha

>> Also read: Interview with Muyiwa Oki

This does not mean that the RIBA should not “simultaneously also listen every day to things that are concerning members,” Bacon says. Other projects in the works include supporting international students who are studying in the UK by linking them back to the institute’s regional chapters in their home countries, and by improving visa arrangements. RIBA is also working on improving CPD on climate change and fire safety, more peer to peer learning, and upskilling professionals ahead of the full rollout of post-Grenfell amendments to building regulations. So how can the institute do all this while reducing its deficit? “It is a consistent challenge, which is why I hope that more members will join,” Bacon says.

The Riba is there for promoting the general advancement of architecture…if somebody wants to start a union, they could easily start a union

One issue Bacon highlights is the steady fall in architects’ fees. According to RIBA figures, the average architect was earning £40,000 in 2013. This rose to £45,000 in 2018, but had fallen to £41,000 in 2021. It means salaries have fallen in real terms by around 20% in the past nine years. “It’s pretty shocking,” Bacon says. “I think people need to feel that the value of an architect is recognised for all the problem solving innovation and care that architects put into projects”. The problem is partly caused by clients increasingly demanding fixed fees, and practices not building enough inflation into those fees.

So what can a RIBA president do to help? Not much, Bacon admits. “I’m not going to give you promises that are not realistic,” she says. “It’s the market. And there is therefore a limit to what an RIBA president can do.” What the president can do is provide training on fees in the form of business CPD and warn architects of the impact that low fees have on employees and the profession as a whole. Practices can also use the RIBA’s fee calculator.

What the RIBA can’t do, Bacon says, is lead industry action. “The RIBA is not a union, and it’s not a business leader,” she says. “The Riba is there for promoting the general advancement of architecture…if somebody wants to start a union, they could easily start a union.” This puts clear water between Bacon and one of her rival candidates, Muyiwa Oki, who is being backed by a collective of activists who are pushing for RIBA to become more of a worker’s organisation than a learned institute - something which would require changing its charter.

But Bacon says the next presidency, which will run from 2023 to 2025 once Allford’s two-year term comes to an end, should focus on climate change and RIBA’s 2030 climate challenge, a set of targets for practices on reducing embodied and operational emissions in their projects. One issue which needs addressing is the difficulty of producing data on emissions faced by smaller practices, which often cannot afford to hire specialists.

Another is greenwash. The RIBA, the UK Green Building Council and other bodies including the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors and the Building Research Establishment are currently working on the UK Net Zero Building Standard, a single agreed methodology which can be used to prove that schemes are genuinely net zero. It would make vague claims on carbon emissions much more difficult to make, and force sweeping changes to how architects in the UK design buildings. It could also make it much harder for practices and clients to justify demolish-and-rebuild projects unless a refurbishment of the existing building can be proved to be unviable.

This could have a major impact on practices which specialise in big commercial projects, including Allies & Morrison. Bacon says RIBA will continue to encourage clients to look at reuse of buildings “where appropriate” - advice which she may want to give one of her own clients. Great Portland Estates appointed Allies & Morrison to design a replacement for a postmodern building in the Square Mile called City Place House, built in 1992. The plans, which were given the green light in July last year, will see a 13-storey office block built on the site.

Allies & Morrison is one of many large practices supporting an industry initiative called Part Z, which is lobbying the government to amend building regulations to include mandatory limits on embodied carbon in projects. Was a newbuild of City Place House unavoidable?

“We are going through our carbon figures very, very carefully,” Bacon says, adding that the City of London’s planning authority was very “challenging” on the issue and decided that a rebuild was a better solution. Bacon herself says in her manifesto that her focus at her practice has been large commercial schemes. As a potential president who, in the same manifesto, says she wants to “consider and promote innovative responses to the climate crisis”, is this slightly problematic? “No, because my last big commercial scheme took 15 years to develop,” Bacon says. “If we were to start that with a brief today, I think the brief would be different. Because practice changes all the time and the challenges change. And we have to be bold and confront the challenges as they come to us.”

Another issue which is at the forefront of this election is bullying in architecture. The findings of an investigation into allegations of sexism, racism and sexual misconduct at the Bartlett school of architecture, published last month, has sent shockwaves through the profession. University College London, of which the Bartlett is a constituent part, has issued an apology. But it added that the “culture of bad behaviour” at the school comes against the context of “longstanding problems with the architecture sector more widely”.

Does Bacon think architecture has a bullying problem? “I don’t come across it,” she says, “but if people are telling you that it exists, one shouldn’t do the equivalent of greenwashing and pretend it’s not happening. We’ve got to listen to the people who are reporting it and make improvements.”

Architecture isn’t a repetitive business, you have to keep learning, keep improving, keep engaging, because the challenges are there every day

At Allies & Morrison, she says she does “everything I can to make this a good workplace”. At the RIBA, she says the institute is “going through a transformation” to get better reporting arrangements in place which she hopes will resolve “any of those kinds of issues that have been there in the past”. The institute has recently launched a new code of conduct for RIBA-validated schools to support architecture students through their studies and protect them from inappropriate behaviour. “It’s all about people and people being decent to people. And that’s critical,” Bacon says.

The importance of treating people well is one of the key lessons she has learned at Allies & Morrison that she will bring to RIBA if elected, she says. “Collaboration has been completely key to the spirit of this place.” Another is to be “prepared to come across something new everyday and deal with it, whether that’s a nice design challenge, or a financial challenge, or an HR problem or a recession over the horizon.

“Everything is different every day. The partners here, we get up and learn something every day from each other. Architecture isn’t a repetitive business, you have to keep learning, keep improving, keep engaging, because the challenges are there every day.

”And that probably is relevant to the RIBA because the challenges seem to be there every day at the moment.”

>> Also read: Why I am backing Jo Bacon for RIBA president

Bacon is not short of high-profile backers. Her supporters include the government’s former chief architect Andy Von Bradsky, Alison Brooks, Barbara Weiss, John McAslan, Simone de Gale, Ken Shuttleworth, Chris Williamson, RIBA board chair Jack Pringle, and her colleagues Bob Allies and Graham Morrison. She is also being backed by Amin Taha, who said earlier this week that Bacon had restructured the formerly “all male and white” RIBA national awards jury to at least half female and a third ethnic minority - and had done so “almost without anyone noticing”.

Taha added that there had been “no convulsing revolution…that could have been met with institutional resistance.” This is Bacon’s style - someone who wants to enact change, but in a way which brings others with her. RIBA is bracing for its new era as a solvent organisation, while managing the expectations of members who are facing an onslaught of pressures. It is now up to voters to decide if Bacon’s style is one they think will work.

Postscript

1 Readers' comment