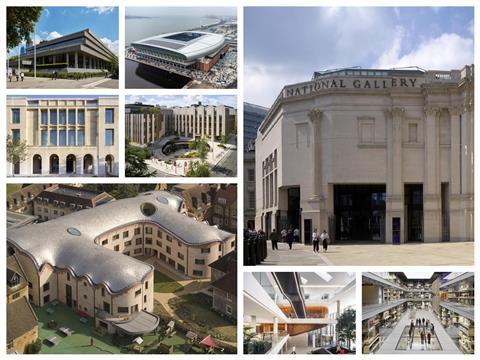

Our pick of the best building studies from the past 12 months

Building Design has spent 2025 visiting some of the UK’s best new buildings, bringing you exclusive stories about how they were designed and built. Here is a selection of our best building studies from the past 12 months.

Designing from first principles: Inside David Kohn Architects’ Gradel Quadrangles

Published in March

Oxford has never been short of architectural ambition. From medieval quads to 20th-century set pieces, its colleges have long used buildings to convey not just status, but evolving ideas about education and community.

Although from the street many appear as bastions of tradition, behind the cloistered walls there is a more urgent dynamic at play. Up until a few decades ago it was normal for students to live in college for their first year and then move into digs of varying degrees of insalubriousness strung out along arteries such as the Cowley Road.

That model has all but disappeared. In its place, colleges are vying to offer a more complete experience – academically rigorous, socially cohesive and spatially integrated.

A cauldron on the Mersey: how Everton built their new stadium in just five years (Manchester United take note)

Published in April

Notorious for going over budget and failing to complete on time, football stadium construction is a risky business. The Tottenham Hotspur stadium was the last big arena to complete in the UK. It was expected to cost £400m but ended up costing £1bn and was delivered seven months late, opening in 2019.

And the recriminations over the additional cost and delays of building the new Wembley stadium resulted in the largest lawsuit in UK construction history.

Everton has avoided this sad legacy, taking just five years from planning application to stadium handover. Admittedly, it spent 28 years thinking about how to increase the 39,572 capacity of Goodison Park and offer improved facilities. But staying at its home since 1892 was not an option as there was no space to expand. The ground is surrounded by homes and a school.

From complexity to clarity: The Sainsbury Wing transformed

Published in May

As the National Gallery approached the bicentenary of its foundation, it embarked on a major renewal programme known as NG200. The project was intended to reframe the institution’s presence in the public life of London and to broaden its appeal to a wider audience. The remodelling of the Sainsbury Wing, now to become the primary entrance for all visitors, is the most visible element of this first phase.

Designed by Venturi Scott Brown and opened in 1991, the wing has now been substantially altered by Selldorf Architects, working with Purcell as heritage architect. Vogt led the landscape design and Lawson Ward Studio delivered a reimagined learning centre at the back of the gallery on Orange Street.

This first phase also includes preparatory works for a second stage of development, due to start in 2026. That will introduce a new underground public link beneath Jubilee Walk, connecting the Sainsbury Wing with the original Wilkins building and a much improved research centre.

Unpacking the museum: the V&A Storehouse in Stratford opens its doors

Published in June

The entrance to the new V&A East Storehouse in Stratford is almost deliberately elusive. There is no fanfare, no grand architectural gesture, just a modest doorway tucked off a quiet street close to the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park.

From the street, this repurposed corner of the former Olympic broadcast media centre could be mistaken for the back entrance to a distribution hub. Only a narrow staircase rising invitingly from the modest lobby hints that something unexpected lies beyond.

“There is no portico outside, there is no big formal entrance,” says Liz Diller, co-founder of Diller Scofidio + Renfro. “It’s very modest. You’re in a working building – not in a place that’s just heroic.”

Designed to change the world: Inside Oxford University’s new £200m Life and Mind Building

Published in December

What do the 3XN-designed New Sydney Fish Market in Australia, Foster + Partners Techno International Airport outside Phnom Penh and NBBJ’s new Life and Mind Building in Oxford have in common? They were all named among the 11 architecture projects set to shape the world in 2025 by US news channel CNN.

The first is designed to give visitors a multi-sensory fish market experience, the second – one of South-east Asia’s largest airports – will put Cambodia firmly on the map and the third seeks to tackle major challenges of life and mind. The Life and Mind Building (LaMB) brings together the departments of experimental psychology and biology and will also house the Ineos Oxford Institute for antimicrobial research.

One of the university’s largest ever projects, the research focus includes investigating fundamental issues including how to address the challenges of climate change, biodiversity loss, mental health and food security. This includes understanding better how natural intelligence works by examining how brains process complex information and modelling those processes with advanced technology to help develop better, more adaptable and useful AI systems.

76 Upper Ground: Denys Lasdun’s 1960s South Bank vision is realised at last

Published in July

Slowly but surely, the public realm on the east side of the National Theatre has got better over the years. A once dismal service road, Stage Door Avenue, between Upper Ground and the riverside path, was improved in 2015 by banishing the theatre’s service yard at the end by the Thames. The former service yard is now a bustling restaurant area and the lorries making deliveries to the theatre and collecting rubbish have largely gone.

But the shine was dulled by the IBM building across the road from the theatre. A high brick wall and brick plinth that shouted “keep out” ran the length of Stage Door Avenue.

The building corner at the Waterloo station end of Stage Door Avenue was sullied by two car ramps; one behind the high wall up to the entrance and the other down to a subterranean car park. Office workers were banished to a pedestrian ramp between the two dedicated for cars, with protection provided by a cheap bus shelter-type canopy.

‘They’re a demanding group of people’… Keeping the scientists happy at the University of Cambridge’s new Ray Dolby Centre

Published in December

As we head into the final month of the year, many in the UK will be turning their minds to gift giving. Each of us has a different idea of what makes a good gift – some might hope for a flashy new gadget from the electronics section at John Lewis, others are happy with something as simple as a bar of Toblerone. But, unless you are the University of Cambridge’s physics department, you probably don’t expect your gifts to come in the shape of an £85m cheque.

To be fair, the donation made by the Ray Dolby (of surround-sound fame) estate in 2017, was large even for the famous university. In fact, it was the biggest philanthropic donation ever made to UK science. Dolby’s gift was to be spent on building a new home for the Cavendish Laboratory, where he received his PhD in 1961.

If you find it hard to imagine giving so generously to your own place of education, you might want to bear in mind the lab’s history. Few research organisations can claim a connection to so many Nobel Prize winners that they lose count. The current tally is 31, after staff found a winner down the back of the sofa.

Oxford opens its doors: Hopkins’ Stephen A Schwarzman Centre for the Humanities

Published in November

For eight centuries, the University of Oxford’s approach to teaching has been rooted in the collegiate traditions which grew out of monastic life. Each enclosed quadrangle formed a self-contained world of study, offering scholars both community and protection from the unruly life of the town beyond the walls.

The organisation of Oxford’s academic disciplines evolved gradually, their boundaries often arbitrary. Over time, the faculties found physical form in separate buildings, each with its own library, offices and sense of identity. The result was a university that was quite often siloed and introspective, united in name but fragmented in architectural space.

Hopkins Architects’ new Stephen A Schwarzman Centre for the Humanities marks a deliberate rethink of these traditions, reflecting new ideas around the role of universities, and the importance of interdisciplinary approaches in academia. For the first time, the humanities – in which Oxford is a world leader – have a collective home.

No comments yet