Ben Flatman explores how the new humanities centre embodies a shift in Oxford’s academic culture. Rooted in tradition yet designed for access, it gives the humanities a shared home and a public face, bridging town and gown through a renewed connection between scholarship and city life

For eight centuries, the University of Oxford’s approach to teaching has been rooted in the collegiate traditions which grew out of monastic life. Each enclosed quadrangle formed a self-contained world of study, offering scholars both community and protection from the unruly life of the town beyond the walls.

The organisation of Oxford’s academic disciplines evolved gradually, their boundaries often arbitrary. Over time, the faculties found physical form in separate buildings, each with its own library, offices and sense of identity. The result was a university that was quite often siloed and introspective, united in name but fragmented in architectural space.

Hopkins Architects’ new Stephen A Schwarzman Centre for the Humanities marks a deliberate rethink of these traditions, reflecting new ideas around the role of universities, and the importance of interdisciplinary approaches in academia. For the first time, the humanities – in which Oxford is a world leader – have a collective home.

The vision of the donor was about making this a public building as much as a university building

William Whyte, chair of the project board

The Schwarzman brings together seven faculties and two research institutes alongside a library, performance spaces and public areas open to the city. It reimagines the university building as not only a place of learning but also, perhaps for the first time in the city, as a civic forum where scholarship and public life can potentially meet on shared ground.

William Whyte, professor of social and architectural history, and chair of the project board, puts the intention plainly: “The vision of the donor was about making this a public building as much as a university building.”

At £185m, Stephen A Schwarzman’s donation is the largest single gift in Oxford’s history. And, after decades of planning, it has finally enabled the long-gestating project to be realised.

Hopkins Architects has responded with a design that seeks to align with Oxford’s architectural traditions, combined with a new sense of openness and a varied cultural programme. The stone facades reference the city’s masonry tradition, while the vast enclosed atrium at its centre provides a new public forum for academic and civic life.

Context and evolution

The Schwarzman Centre stands on the site of the former Radcliffe Infirmary. When the hospital closed in 2007, the university acquired the land to create the Radcliffe Observatory Quarter (ROQ). The ambition was to create a new academic district and deliver the long hoped-for new humanities hub.

Rafael Viñoly’s masterplan – later revised by Níall McLaughlin Architects – set the broad development framework for the site. It was a rational diagram rather than a convincing vision for a new piece of city.

Initially it seemed destined to produce a campus more reminiscent of an edge-of-town science park than a natural extension of Oxford. Subsequent buildings have responded to and adjusted to that plan in different ways, but its underlying limitations remain visible in the so-far disjointed and architecturally incoherent quality of the new district.

Hopkins Architects entered this setting with a building that fills the most prominent plot. A humanities institute designed by Bennetts Associates was approved for the site in 2010, with two interlocking L-shaped buildings creating an open quadrangle. Due to funding issues, that building never materialised, although Viñoly’s own underwhelming mathematical institute opened in 2013 and squats awkwardly in the east of the ROQ.

The Schwarzman is more formally conservative and self-contained than the earlier Bennetts scheme, eschewing the quadrangle for what is essentially a perimeter block with a covered courtyard. Its stone facades give it weight and presence, and it attempts to assert a civic presence which the original masterplan perhaps lacked.

Whyte, the university’s senior responsible owner for the project, stressed the need for the building to anchor the quarter: “It needed to hold the site. It needed to look as though this was the building around which the other ones had grown up.”

That intention is most visible on the building’s northern side, where it faces the grade I listed Radcliffe Observatory. The donor is also funding a project at Green Templeton College to reorient its entrance away from Woodstock Road, to the south and the observatory, giving this new relationship an even greater prominence.

To its south, the Schwarzman butts up rather uncomfortably with Herzog and de Meuron’s Blavatnik School of Government, a building which in any case never really invited an urban conversation. The Blavatnik is the archetpyal freestanding modernist object in space, while the Schwarzman seems designed for some New Urbanism development that is yet to fully materialise.

The eastern and western edges of the quarter remain unresolved. A large plot to the Schwarzman’s west lies empty.

Future development, including Morris + Company’s Ratan Tata Building for Somerville, will determine whether the ensemble ultimately acquires the coherence Oxford hoped for when it took on the site. For now, the Schwarzman Centre acts as the district’s focal point, even if the wider plan has not yet fully caught up.

Architecture and urban form

The Schwarzman Centre’s primary facades are faced in Clipsham stone to the north and south, with brick to the east and west. The construction, handled by Laing O’Rourke, used prefabricated panels assembled off site and craned into place. The approach gives the appearance of traditional ashlar while achieving the precision and speed of modern assembly.

Andrew Barnett, principal at Hopkins, describes the language of the building as “an attempt to use the lexicon of Oxford masonry”.

As the home of the humanities, we felt strongly that it should speak to the core masonry buildings of the university

Andrew Barnett, principal at Hopkins

“Stone was in our brief,” he explains. “As the home of the humanities, we felt strongly that it should speak to the core masonry buildings of the university.”

There is a disavowed traditionalism in Hopkins’ composition of the primary elevations. But the overall effect is perhaps less reminiscent of Oxbridge collegiate architecture and more akin to early 20th-century stripped classicism. The Schwarzman would not have looked out of place in Herbert Baker’s Pretoria or Lutyens’ New Delhi.

Hopkins as a practice has of course done brilliant work in melding modernism with a sensibility sympathetic to historical reference. It is also adept at the use of heavy masonry juxtaposed with high-tech structure.

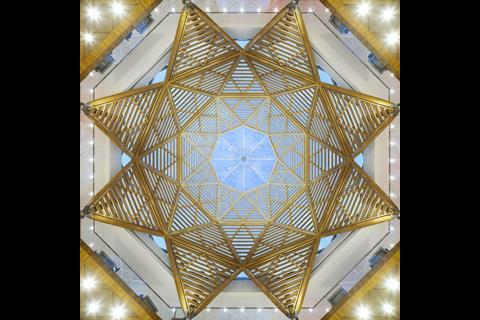

This more familiar language is immediately evident inside, where the tone changes. The Great Hall at the centre of the building serves as Oxford’s first true university forum.

Its vast atrium rises through several floors beneath a glass and steel dome. Steve Holland, contractor Laing O’Rourke’s project director, recalls that “each dome was preassembled adjacent to the building and then craned into place as a single piece. The accuracy had to be millimetre-perfect.”

The atrium has immediately established itself as a vibrant social hub. From the first day of opening, students began to use it as a meeting and workplace. Compared with the libraries of the university, which have traditionally been silent, the Schwarzman Centre provides a buzzy, animated point to meet and collaborate.

The Great Hall spills over into cafes at ground level and informal study terraces on each floor of the surrounding galleries. Whyte observes that “every space has to do more than one job. It’s a working building that’s also about communication.”

This is also true of the Great Hall, which is designed to accommodate lighting rigs for performances.

As Whyte notes of the atrium: “It also serves the function of being a little bit like the Schools Quadrangle in the Bodleian Library in that it is also a space where you can orientate yourself.”

Each faculty is marked by its name above the door, he explains, so that students can see at a glance where English, history and modern languages are housed within the building.

The Bodleian Humanities Library sits on the north side of the upper floors, uniting seven collections across roughly 2,100 square metres on three levels, with around 340 reader seats and some 200,000 titles. It is designed to knit closely into adjacent faculties and the Great Hall, so that readers move easily between study and teaching spaces.

Beyond the atrium, the tone shifts to something more conventional. Offices and seminar rooms line the perimeter floorplates, where the architecture becomes quieter and more functional, a reminder that the university’s tutorial system still depends on privacy and one-to-one contact.

The contrast between the generous public heart and the compact faculty spaces sets the building’s rhythm: communal at its centre, introverted at its edges.

Yet it is around the perimeter that the building is least convincing. With nearly a thousand rooms, the highly cellular, conventionally planned faculties lack a sense of dynamism. Standardised materials and finishes lend a muted, corporate quality to these academic areas.

Cultural core

At the Schwarzman Centre, Hopkins Architects has had to reconcile an exceptionally complex brief, balancing the needs of multiple faculties with the creation of a new cultural hub for the university. At the lower ground floor, reached by a grand staircase which descends to a red-carpeted foyer, the building reveals its most unexpected spaces.

This sequence includes the 500-seat Sohmen Concert Hall, a 250-seat theatre, a recital room and a black-box laboratory for experimental performance.

The arrival sequence feels appropriately theatrical and immersive, setting the tone for what follows. The concert hall itself is the standout set-piece: astonishingly large within, it is difficult to believe, looking from the outside, that such a space could be contained within the building’s envelope.

“The concert hall is a box-in-box construction floating on 70 rubber bearings” Holland explains. “It has its own structural frame, completely separated from the rest of the building, so no vibration or sound travels through.”

Andrew Barnett, principal at Hopkins, describes the performance areas as “some of the most technically demanding spaces we have ever worked on”.

Barnett has again taken inspiration for the concert hall from the city’s wider architectural heritage. “We came up with this solid timber ‘top hat’ above the hall – it adds volume and bounces sound back down like the heavy timber roofs of Oxford’s great halls and chapels.” Inside, the atmosphere is warm and tactile.

The timber panelling has been hand-veneered by James Johnson & Co. As Whyte observes: “It’s a wonderful kind of combination of traditional concert hall and traditional craftsmanship and the latest technical design.”

Sustainability and construction

The Schwarzman Centre is the largest building in England designed to Passivhaus standards, setting an ambitious benchmark for energy efficiency and environmental performance. Achieving certification at this scale required extraordinary airtightness, minimal thermal bridging and exceptionally high levels of insulation.

Barnet says the team was determined to make the building exemplary “both in energy terms and in the way it was made”. Meeting the stringent Passivhaus criteria also shaped the building’s overall form and massing.

“We worked incredibly hard on the plan to shrink the mass as much as possible,” Barnett explains, noting that the need to minimise the envelope was one of the reasons why an open-air quadrangle was ruled out.

For Laing O’Rourke, the challenge lay in delivering such performance in a building of this size and complexity. Holland describes the approach as “wrapping the building in the best part of three to four football pitches of insulation”. Achieving this precision required close digital coordination.

“Everything was coordinated through BIM,” he says. “We manufactured off site and brought it to site like a kit of parts.”

Prefabrication extended to facades, roof structures and many internal components, reducing waste, improving quality control and ensuring accuracy throughout.

Sustainability also extended to procurement and sourcing. Of the project’s subcontractors, 97% were based in the UK. “We tried to keep the supply chain as local as possible,” says Whyte. “Rutland stone, York bricks, steel from Bolton, architectural steel from Sheffield…”

The result is a building which marries advanced digital construction with a strong commitment to local craftsmanship and material integrity, reflecting the project’s wider ambition to unite innovation with tradition.

A new civic relationship – bridging university and city

From the outset, the Schwarzman Centre was conceived not only as a home for the humanities but also as a shared resource where the boundaries between university and city life could begin to blur. Increasingly, universities are being asked to give back to the places they inhabit and, for Oxford, this project marks a clear acknowledgement that it must engage more fully with the city around it.

The centre’s mix of academic, cultural and outreach functions reflects a deliberate effort to make the university more visible, accessible and relevant to a wider public.

That ambition is expressed architecturally as well as programmatically. The vast glass dome which crowns the central atrium is the building’s most striking feature, yet it cannot be seen from the surrounding streets. Oxford’s long-standing height restrictions required the structure to remain below the height of Carfax Tower, except in rare cases such as the new tower at David Kohn Architects’ Gradel Quadrangles for New College.

Perhaps it is a missed opportunity: a visible landmark could have signalled the presence of this new civic space and announced a more open relationship between university and city.

Despite this, the project does signal a broader shift in how the university seeks to see itself: less an enclave of cloisters and libraries, and perhaps the beginnings of an institution more closely woven into the broader life of Oxford.

The Schwarzman Centre suggests how the university can evolve, from its inward-facing traditions towards a more open and participatory model of academic life. Whether it succeeds in transforming that culture will take time to tell, but it may yet prove to be the building through which the university finally learns how to open its doors to the wider city.

>> Also read: Designing from first principles: Inside David Kohn Architects’ Gradel Quadrangles

>> Also read: Cohen Quad, Exeter College by Alison Brooks Architects

Project team

Client and lead: Estates Services Capital Projects, University of Oxford

Architect: Hopkins Architects

Construction partner: Laing O’Rourke

Structural designer, novated: AKT II

Building services designer, novated: Max Fordham

Theatre consultant: Charcoalblue

Acoustic consultants: Arup and Max Fordham

Passivhaus consultant: Etude

Fire engineer: Fire Ingenuity

Landscape design: Gillespies

Project manager: CPC Project Services

Cost consultant: Arcadis

Contractor architect: Purcell

Mechanical and electrical services: Crown House

Piling and structure: Expanded Piling

Facades: Vetter

Windows and doors: Britplas

Hybrid steelwork: Severfield

Dome: Novum

Performance space fit out: James Johnson

Timber linings: WJL

Joinery: Quest

No comments yet