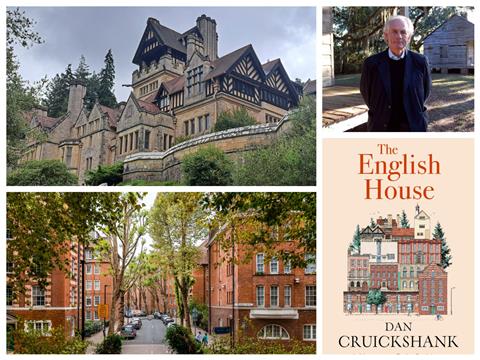

Architectural historian Dan Cruickshank’s new book charts 200 years of British domestic architecture through eight carefully selected properties, from Georgian townhouses to the first modern house, exploring how social history, economics and cultural taste have shaped the way we live. Review by Daniel Stilwell

Ideas of house and home play a subtle game of semantics but their distinctions are important useful exercises to think about. We could go as far as to establish the house as the physical construction, the ‘bricks and mortar’ of a dwelling; of floors, walls, ceilings, windows and doors. The home then, is defined as something more immaterial, more personal and influenced by its inhabitant more overtly. In this context, it is tied up with how we decorate its interior, how we furnish it or the everyday practices that unfold inside of it; washing, cooking, cleaning and sleeping.

For anthropologist Mary Douglas, the home was a space that had qualities of familiarity and a sense of control to it but was not stable physically. In her 1991 essay The Idea of A Home: A Kind of Space, Douglas wrote that the “Home is located in a space, but it is not necessarily a fixed space.”

Our ideas of home can then be seen as being constructed from both the physical and the immaterial - moving with us as we move. At any one time, it holds attachment and memories as well as its own physical history. It might also be full possessions and domestic artefacts as accumulations of a life.

The English House: structure and approach

For Dan Cruickshank and his new book The English House, British domestic architecture has a much richer history than the physical construction presented to us at face value. His focus holds both house and home in equal measure. We are reminded the house can be a status symbol, a typology ripe with innovation and invention but also that it plays an essential role in our everyday lives; for shelter, security, and comfort.

Cruickshank shifts focus within each house history, jumping between the obvious form, style, layout and decoration to the inextricably linked social histories

The structure of The English House is simple and moves us chronologically through a little over 200 years of British domestic architecture in eight ‘portraits’ or houses - stopping at the ‘first’ Modern house in 1925. Cruickshank shifts focus within each house history, jumping between the obvious form, style, layout and decoration to the inextricably linked social histories each of his chosen houses hold.

For Cruickshank, domestic architectural history is not simply what each houses’ architect believe to be good and proper or what their clients deem to be tasteful or affordable but how they were to be lived in too.

We are introduced to the fact these houses are conceptually held together in this book through the relationship explored; between client, inhabitant and architect to a host of craftspeople and builders - turning anything from sketches and ‘modells’ into physical manifestations of housing.

Pallant House, Chichester: Georgian townhouse architecture

In some cases, there is no named architect. This is true of the first house, Pallant House, an early 18th century (1712) townhouse in Chichester built for the newly married Henry Peckham and Elizabeth Albery.

It is perhaps now better known as Pallant House Gallery, having been converted in the 1980s with the donated collection of Dean of Chichester Cathedral Walter Hussey forming the first set of works. Its more recent past has a gallery extension by Wilson and Long & Kentish which opened in 2006.

We can see it is considered, formal and almost symmetrical on the street facing elevation (its extension not withstanding). It was a house built at the end of the Queen Anne period and the cusp of the birth of Georgian architecture in Britain. Its entrance adored with what are meant to be stone carved ostriches although many believe look more like Dodos, from the Peckham arms, symbolising both class and status.

Pallant House had an acrimonious start, middle and end. As was usual in the 1700s, Albery was to forfeit the majority of a £10,00 inheritance from her brother when marrying Peckham in 1711 - of which she was against for obvious reason.

The couple divorced in 1716 and plunged themselves into legal disputes until 1720 on the grounds of spiralling construction costs on under Peckhams control, of which he suggests Albery was complicit in. To make matters worse, Cruickshank elaborates that Peckham had engaged in financial abuse of Albery and her inheritance, with shady and fraudulent activities.

Cruickshank highlights Alberys fundamental involvement in the planning and design of Pallant House, giving her a notable authorship and we’re left with the impression of a client as architect, and rarely, Albery herself. Cruickshank name drops Bess of Hardwick as precedent here as a woman fundamental to the orchestrating of a design in Hardwick Hall over a century earlier.

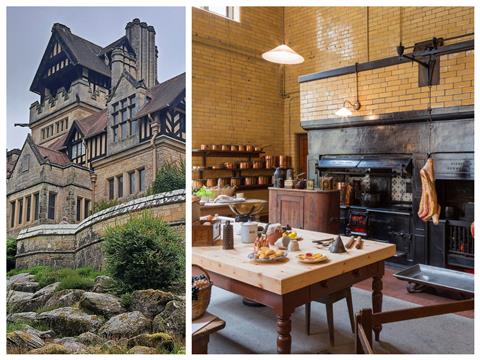

Cragside, Northumberland: Richard Norman Shaw’s Gothic Country House

One of the larger and longer builds featured is the extension of a small shooting lodge into the country house behemoth Cragside, a proto-‘don’t move, improve’ in the 1860s by Richard Norman Shaw and starring a gutsy and overwhelmingly ornate inglenook by William Lethaby - who was Shaw’s Chief Assistant in the 1880s.

Commissioned by Lord William and Lady Margaret Armstrong, whose wealth came from Armstrongs background in engineering and various ventures as an industrialist and inventor. This sizeable 26 year long project in Northumberland had Shaw design and add to the sprawling hillside house incrementally. Chunk by chunk, room by room.

Cragsides half timbered sprawling nature means in one breath it shows off its Gothic and Old English Style mannerisms, notably externally and in another breath, Jacobean and Renaissance internally, particularly as Shaw added more to his assemblage over time.

Certain ‘home-making’ elements were incorporated into the longstanding project to imbue a sense of comfort via its plumbing and drainage alongside, eventually, whole house electricity generated by water power - introduced by Armstrong in 1878 - making it the first British house to be illuminated by electricity.

The Boundary Estate, Shoreditch: Britain’s first council housing

The second to last house sees us visit the largest project of the book, housing some 5,500 people across 1,069 separate tenements. The London County Council’s Boundary Estate (1890 - 1900) in Shoreditch cements the birth of the council estate and the council flat. The numerous buildings within the cyclical planned estate were principally overseen by Owen Fleming, a rising talent Cruickshank notes, and a team of young LCC architects.

Their principal goal was to design in comfort, convenience health and beauty. This was then manifest into an architecture that spoke of the Queen Anne Revivalism seen across Britain.

This architectural translation was as Cruickshank explains, one of Dutch influence seen in the gables, large white painted sashes and a palette of red bricks striped with Portland stone - offering up soft Arts & Crafts mannerisms into the mix.

The ambitions here proposed large social impact, reflected in the planning and layout of houses here in generous proportion. But Cruickshank attests, not everything was for common good and a large majority of those who lived in the existing Old Nichols slums destroyed by the building of the Boundary Estate were never rehoused in them, were displaced and ultimately forced to continue living in slum conditions but elsewhere nearby.

Princelet Street, Spitalfields: Immigration and adaptive reuse

In between these houses, we’re offered up a house for immigrants in 19 Princelet Street in Spitalfields, built in 1717. What was once a modest merchant house and home to the Huguenot Ogier family; Peter Abraham Ogier a successful silk merchant and weaver, ended up with a 19th century synagogue built in its back garden.;

We move to Hull and Maister House (1743 - 1760) next, its owner, Henry Maister rebuilt his family home after a fire destroyed it, taking his wife, an infant son and several servants, whilst attempting to escape. His ambitions then, were to build a house that was bigger, better but importantly of more fireproof construction.

From Hull to Liverpool in Heywood’s House and Bank (1798 - 1800), is an example of a house born out of and paid for exploitation; through war and latterly extreme involvement in slave trading, with the wealth generated, establishing their banking legacy. Cruickshank suggests some 133 voyagers were invested in, totalling an estimated 42,000 people between 1745 and 1789.

Moving across Liverpool to the inner city densification of Toxteth, we see a governmental response to rising problems around health and well-being for rapidly growing Victorian towns and cities. The development of Bye-Law houses via new national building standards allowed the likes of Welshmen Richard Owens (carpenter and foreman turned speculative builder and architect) and David Roberts (timber merchant) to develop a thriving business, building some 4,300 houses between the 1860s - 1890s.

The last of the eight houses seems insignificant only in scale after reading about the mammoth building of the Boundary Estate. The focus though is Peter Behrens’ New Ways in Northampton (1925-6), labeled the first ‘Modern’ house. Its client and owner Wenman Joseph Bassett-Lowke had history of commissioning well known architects; having worked with Charles Rennie and Margaret Macdonald Mackintosh to remodel 78 Derngate a decade earlier in 1916, also in Northampton.

The English House highlights architecture as an important backdrop to everyday people and places. Equally, it shows the influence that society has on architecture to better living conditions and provide home comforts for the masses, how cultural tastes shape style wars as well as how economic pressures can add to and re-make the shape of the home.

One might question why end there? For Cruickshank, the house as an idea, endures history, fashion and taste. It transcends notions of comforts afforded to its inhabitants and can hold the most vernacular of details to the hotly invented modern lifestyles. It is timeless and unchanging in one breath yet radically flexible and adaptive to the desires of society and culture in another.

Historian E.H. Carr, in What is History? (1961) writes that “History requires the selection and ordering of facts about the past in the light of some principle or norm of objectivity accepted by the historian, which necessarily includes elements of interpretation. Without this, the past dissolves into a jumble of innumerable isolated and insignificant incidents, and history cannot be written at all.”

To that end, Cruickshank follows suit in his pursuit of selection and ordering of facts that stretch what British domestic architecture is and can be in these combined histories.

The continued passing of stories and lived experiences throughout history relies on it being a collective one, reliant on others (re)interpreting what was left behind. The convincing use of social histories alongside its architectural counterpart reflects contemporary architectural history scholarship that is expansive and multidisciplinary. This work though is still indebted to the old school historian, evident in both the dedication of The English House but also in Cruickshank’s re-telling of Cragside, celebrating Andrew Saint, the authority on Shaw.

This feels especially poignant given Saints passing earlier this year and adds to Cruickshank’s portrayal of Shaw’s mightiest project.

Cruickshank shows us in each example of The English House that they are as much a product of their times and not only of architectural making but are ferociously influenced by society, culture and economy. They are mirrors into Britishness for good but also bad.

Postscript

Daniel Stilwell is an architect and historian at Charles Holland Architects and teaches at Canterbury School of Art, Architecture and Design & Central Saint Martins. He designs and writes on the history of the home, domestic life and comfort, and specialises in the Arts & Crafts movement

2 Readers' comments