The Weight of Being: Vulnerability, Resilience and Mental Health in Art runs until 19 April and brings together a diverse selection of works by contemporary and 20th-century British artists to explore some of the ways in which mental health shapes artistic expression, Sarah Simpkin reports

Two Temple Place is the lignophile’s dream. Imagine being the woodlouse that gets to tunnel through a carved oak frieze of Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra. The experience is similar for the visitor moving through its ornately panelled halls.

The building has opened its doors to the public again for a major free exhibition, The Weight of Being: Vulnerability, Resilience and Mental Health in Art, which runs until 19 April. The show brings together a diverse selection of works by contemporary and 20th-century British artists to explore some of the ways in which mental health shapes artistic expression.

The fantasy fortress on the Embankment

Two Temple Place, on London’s Embankment, was built as offices for American hotelier, politician and publisher William Waldorf Astor in the 1890s. It was designed by the architect John Loughborough Pearson as the ultimate neo-gothic oligarch’s mansion, with historical fakery writ in real materials: ebony pillars, carved mahogany figures and friezes in hard, unmalleable oak by the leading artists of the day.

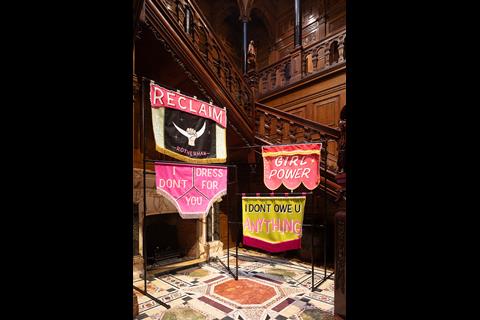

Colour comes from the contrasting hues of endangered woods and the rare marble inlaid in the geometric “Cosmati” floor. The centrepiece is a galleried staircase under a stained-glass ceiling that has graced numerous period dramas and wedding photos.

The Astor family’s fortune was originally made in the fur trade, then through real estate – both extractive forms of enterprise that profited from unequal labour and the ills of 19th-century capitalism. The Bulldog Trust, the charity that now runs the house, appears to take the programming of the building as an act of reparation; the focus is on exhibitions and workshops that platform underprivileged groups and show pieces from regional public collections. Last year’s headline show, Lives Less Ordinary, explored working-class life in British art in a deliberate juxtaposition.

A significant focus of The Weight of Being is the paintings of John Wilson McCracken (1936-82); the show is a vehicle for giving his work greater prominence. McCracken studied at the Slade School of Art in the 1950s, frequenting Francis Bacon’s iniquitous Soho, but after he was hospitalised for his mental health, his mother took him to Hartlepool, where he had relatives, for a quieter life.

He became an important figure in the region’s art scene, which grew with his influence and that of his contemporaries. Their international reach is evidenced in a vitrine of exhibition posters and issues of Iconolatre painting and poetry magazine, which featured work by Charles Bukowski.

The relationship between environment and mental health

McCracken’s figurative work is set against simple furnishings and bare interiors: a man in a pub, hunched over a slip of paper with a half-full (or half-empty) pint, a self-portrait in a bathroom mirror, a woman in an apron cleaning a cafe table.

The relationship between the built environment and mental health is not given an obvious narrative; the approach to the “personal pressures on the individual and the universal challenges faced by humanity as a whole” is necessarily broad.

There is a wall on the “architecture of class”, contrasting poverty in rural Norfolk via Jim Mortram’s Small Town Inertia with bleak Thatcher-era Belgravia rooms photographed by Karen Knorr. Further on, in a room of meditations on landscape, there is an intricate painting by Geraint Evans of a zen garden on a traffic island. Later, a painting of a public bench wrapped in hazard tape during the covid-19 pandemic by Narbi Price.

It is a “show” rather than earnestly “tell” approach to examining cause and effect between living standards and quality of life.

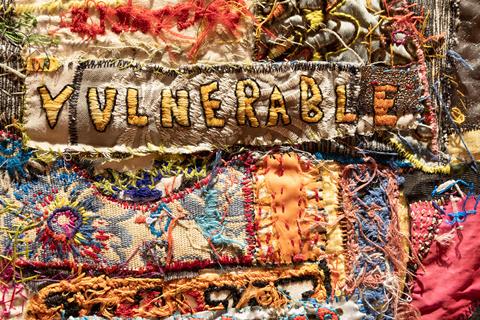

The Weight of Being has been curated by Angela Thomas, who leads the programming of Hartlepool Art Gallery. “[The show] does not offer solutions,” Thomas explains. “It does not pretend that art can cure, fix, or neatly resolve. Instead, it invites us to sit with vulnerability and hope, and to see how they coexist.”

The impression as you walk around is of the universality of these experiences. How we all deal with the world as it is, as it has been, and how that finds form in art.

Alongside more reflective pieces, there is protest as resilience. At the foot of the staircase are brightly sewn ”Girl Power” and “I Don’t Dress for You” banners by Jenna Greenwood, comically offset by the mahogany carving of D’Artagnan, one of the Three Musketeers on the balustrade. Or forever Dogtanian, if you are over a certain age.

Unlike exhibitions that showcase works by patients in the mental health system, there is no artificial distance between the visitor and the artist, who is presented as in some way “other”. Neither does it dwell on the trope of the tortured artist, the over-trodden line between creativity and sanity.

Rather, it is a reflection of “the weight of everyday”, of shared experience and resilience. It is also a chance to see Maureen Scott’s painting, Mother and Child at Breaking Point, 1970. This was a standout moment in Tate Britain’s Women in Revolt! show a couple of years ago for the tired resignation in the face of a mother holding a distraught toddler in a kitchen.

The exhibition continues upstairs in the former library, which has an unusual door. Two Temple Place’s director, Paddy Altern, points out that while the door is clearly legible on the public side in the adjacent Great Hall, it is concealed within the satinwood panels once we are inside the private space.

It creates a cocoon from the outside world, like a Victorian panic room. As well as being an elaborate setting for the art, vulnerability – one of the themes – is also expressed through the architecture, in the legacy of the American that faked his own death and built a gothic gesamtkunstwerk to hide in.

Postscript

The exhibition is free and runs until 19 April: https://twotempleplace.org/events/the-weight-of-being/

The Weight of Being is produced by Two Temple Place with the support of partners: Bethlem Museum of the Mind, Hartlepool Art Gallery and Hartlepool Borough Council, Andy’s Man Club, Hospital Rooms and West Central London Mind.

No comments yet