Scotland already meets much of its energy needs from renewables – now, says Rab Bennetts, its buildings must reflect the realities of its climate, with a focus on mass retrofit and upgrading the housing it already has

Back in the early 1990s, when sustainability was still called energy efficiency, Bennetts Associates built one of a series of what we would now call low-carbon buildings in Edinburgh for John Menzies. Having developed ideas about natural ventilation, solar control and thermal mass at our Powergen project in Coventry, we were keen to understand how local weather conditions would influence the design.

The M&E engineer from Blyth & Blyth said, “Just remember, laddie, this is where the snow falls on the walls, not on the ground!”

Sure enough, with his witty counsel ringing in our ears, the strength of the wind, the cooler temperatures and the lower sun angles led to a significantly different design to the preceding project just 300 miles further south. It was a classic case of ‘think local’, as the green mantra goes.

It became obvious that the long heating season was key, whereas at Powergen much of the effort went into avoiding summer overheating and air conditioning. Unable to rely on opening windows in high winds and cold conditions, in Edinburgh we opted for mixed-mode, manual windows being seen as a bonus in good weather. The façade, too, was markedly different, as an external solar filigree would have been vulnerable to the wind.

The climatic differences between Edinburgh and Coventry, not to mention later projects in Brighton, Bath and Aberdeen, kicked off a range of ideas about local weather conditions influencing the form of architecture round the world - an antidote, if you like, to the uniformity of globalisation.

I might be unpopular for saying this, but I’m now concerned about air-tight standards such as Passivhaus

To take one small example, I find it intriguing that tall windows in historic Italian villas have slatted shutters on the outside to keep out the sun and allow the breeze to infiltrate, whereas in elegant Georgian and Victorian Edinburgh, solid shutters are on the inside to keep the place warm. Well, warmish.

To cope with the climate, Scotland’s historic buildings have always been rugged and robust, but restricted availability of materials has led to an architecture that is distinct to those in other cooler climates, such as Scandinavia, where timber is much more evident. One could argue that Scotland’s own timber industry has been greatly neglected, partly due to land ownership and a forestry policy that wasn’t developed with construction in mind.

My old friend Peter Wilson of Mass Timber Initiatives despairs at the huge advances made by European timber industries, while many Scottish firms seem content, as he says, ‘to make pallets’. Let’s hope the research being done at Scotland’s national innovation centre BE-ST (Built Environment, Smarter Transformation) can change attitudes.

Climate change has brought another range of challenges, though, with greatly increased rainfall exposing the inadequacies of traditional gutters, flashings and downpipes in historic properties. Condensation in a cool climate has also been the bane of many reinsulated housing projects, notably those from the post-war period.

I might be unpopular for saying this, but I’m now concerned about air-tight standards such as Passivhaus, which is seen as the benchmark for most if not all new Scottish housing and some schools.

High levels of air-tightness and insulation are certainly energy efficient, but there’s something about Passivhaus that feels too controlling and, dare I say, joyless. Would some larger windows with a view really be such a sin?

No doubt there are marginal carbon implications for more air and better views, but Scotland’s energy is far more ‘renewable’ than the UK as a whole. Looking at the daily National Grid data, it’s common for Scotland to meet its electricity needs from renewables alone, most of which is wind power.

As with so many aspects of sustainability, thinking locally is a large part of the solution

Plugging very large wind farms into the UK National Grid is no easy task, so there is an argument for Scotland’s industry and homes to have direct use of locally generated, cheaper energy. Perhaps this could help to support heavy energy-using businesses relocating to Scotland, as demonstrated by Sweden.

As with so many aspects of sustainability, thinking locally is a large part of the solution. I visited a brilliant example of hydro power recently at Blair Atholl estate near Perth, where architect Jamie Troughton (who was once in partnership with John McAslan) has installed six small hydro schemes that have paid back the investment in no time.

For Scotland as a whole, the elephant in the boiler room is gas, which dominates Scotland’s domestic heating market at a scale that will be extremely difficult to replace with renewable electricity. Much attention is lavished on new-build ideas like Passivhaus, but the real issue is the huge quantity of existing housing that needs to be upgraded within the next decade or so if climate commitments are going to be met.

There are also logistical difficulties in cities, with many homes in tenements with multiple owners. The suspicion is that the politicians, not just in Scotland but everywhere, have little sense of how this can be done, let alone afforded. Moreover, the evidence from favoured methods like communal heating is that they are nothing like as efficient as is claimed.

As I look out from my flat in Edinburgh’s Quartermile across nearby Marchmont and Tollcross, nearly all the buildings are more than 100 years old. It follows that most of the buildings to exist in 2050 are already built, so the mission must be to roll out upgrades en masse and pursue renewables as if there was no tomorrow.

Postscript

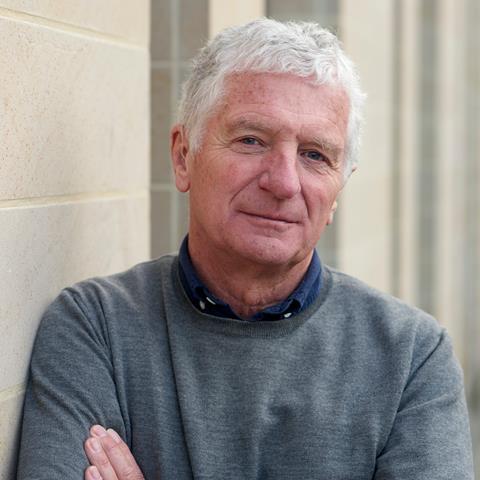

Rab Bennetts co-founded Bennetts Associates in 1987 with his partner Denise Bennetts.

No comments yet