Given the high proportion of public sector projects and the number of small practices operating on tight margins, attempts by the RIAS to improve an unsustainable situation are most welcome, Rab Bennetts writes

Of all the issues affecting Scottish architects, there is near unanimity on one – the disastrous state of procurement, especially in the public sector. An online discussion group at the RIAS regularly yields horror stories about unfair and costly selection procedures, suicidal fee levels and the (probably unwitting) exploitation of the profession.

These are not isolated examples from disaffected losers – they are too consistent for that – and the consensus is that fee levels have halved in the past decade. Yes, half. It goes without saying that this is unsustainable and many architects are now avoiding the public sector completely.

Procurement is far from easy anywhere in the UK, but in Scotland it appears to be especially severe. The public sector accounts for more than 50% of the total economy, which reflects long-standing policies of higher spending than “down south”.

Government competence is also under fire right now for its disastrous intervention in the construction of new ferries for the Western Isles, which no doubt means politicians are scared of anything that is not the lowest cost but, as we all know, doing things “on the cheap” in the built environment can lead to serious long-term failures.

Government policy intended to support the nation’s SMEs clearly contradicts procurement rules that result in the opposite

Another factor unique to Scotland is its high percentage (90%) of small practices, which means that most architects cannot qualify for work in the largest part of the economy even if it is available, thanks to size and experience-related selection criteria. Younger practices are simply not breaking through into larger projects like they were a decade or two ago, which does not bode well for the future.

Contracts are also frequently bundled into large frameworks operated on a lowest risk basis by various management companies, reinforcing the detachment of local architects from projects that would easily be within their capabilities. Government policy intended to support the nation’s SMEs clearly contradicts procurement rules that result in the opposite.

The emergence of these frameworks over the past few years also comes with extreme pressure from competing managers to reduce architects’ fees, where figures between 1% and 2% are not uncommon. All architects know that you cannot design and execute a significant building at this level and, from anecdotal experience, the result seems to be a contractor-like reliance on claims, which was professional anathema not long ago.

As if that is not enough, many public sector clients genuinely do not seem to understand how their chosen assessment criteria affect the outcome. The ubiquitous quality:cost ratio may seem benign if the numbers appear to favour quality. But it is widely understood within the profession that 60% quality:40% cost in practice means that the lowest bid wins every time and some eligible architects are simply declining to bid unless the ratio is at least 70:30 or better. Recent feedback has shown that several public sector clients in Scotland are actually promoting 20% quality:80% cost, not the other way round!

Many practitioners would welcome more of this from the RIAS and RIBA alike, as individual practices are not in a position to bite the hands that may feed them

The RIAS is actually doing something about this, not only by engaging with the Scottish government in industry-wide consultations, but also directly with key local authorities to get them to change the terms of the bids, with some notably successful results. I am sure that many practitioners would welcome more of this from the RIAS and RIBA alike, as individual practices are not in a position to bite the hands that may feed them.

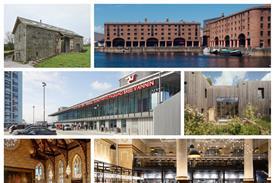

There is a twist, though. A few major projects do get high-level attention when it comes to procurement, particularly when a public sector client has clout and vision but, for many Scottish architects, there is the sense that to win these “iconic” projects you have to be based outside Scotland. Hence, we have Kengo Kuma’s V&A in Dundee, Steven Holl’s art school block and Zaha Hadid’s transport museum in Glasgow, Amanda Levete’s museum in Paisley and David Chipperfield’s concert hall in Edinburgh.

I do not share this view as I have heard equivalent moans about this from London architects too, but there is no doubt that procurement in Scotland is the source of much gloom and pessimism. Let’s hope the RIAS’s vigorous approach helps to turn things around.

And what of the risks of procurement rules based on what has been described as “a race to the bottom”? Clearly, there is the risk of firms not surviving to the end of a project, but there is also the risk of actual building failure due to excessive use of junior staff or short-cuts with design information and on-site inspections.

In this context, the Grenfell report makes extremely painful reading, but there are Scottish examples of procurement failures too, such as the collapse of brickwork on Edinburgh schools and a disastrous leisure centre in Dumfries & Galloway. If poor procurement was directly linked to poor buildings, it would surely be possible to recalibrate the relationship between good architects and better outcomes for their patrons – the public.

Postscript

Rab Bennetts co-founded Bennetts Associates in 1987 with his partner Denise Bennetts.

1 Readers' comment