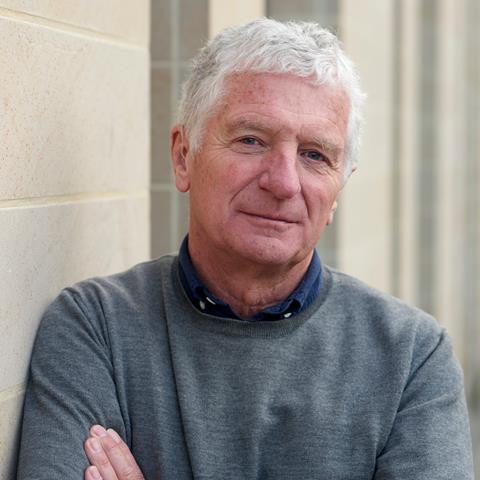

Rab Bennetts begins his new column for BD with a look at Scotland’s architectural landscape, shaped by small practices, challenging procurement and a tough economic climate

It may be apocryphal, but I was once told there are as many architects in London’s Clerkenwell as the whole of Scotland. Having spent much of my career in the former, with frequent visits to the latter, I am now based in Edinburgh for the first time since student days, better placed to observe the disparity of scale and intensity of activity.

The Royal Scottish Academy’s (RSA) annual exhibition is one of the few barometers of the architectural scene in Scotland and I am always struck by the contrast between the large and the small that you wouldn’t see at, say, the Royal Academy Summer Show in London. It’s immediately evident that many Scottish architects, the vast majority of whom are very small practices, revel in the restraints of rural and often remote locations that are a world away from the larger projects found in the four big cities - Glasgow, Edinburgh, Aberdeen and Dundee.

If spectacularly beautiful sites are not sufficient inspiration in themselves, there is a cohesion within this group of exhibits borne of similar scale, response to the extremes of weather, use of materials, construction technique, resource efficiency (including recycling or adaptation) and - remarkably often - independence from the national grid. Some may be second homes but others are clearly permanent residences, where the occupants are admirably determined not to be a burden on the planet.

In terms of form, the transparency of modernism has yielded to greater solidity, but there are still choices being made about visibly asserting confidence or merging with the background. Practices like Dualchas or Anne Nisbet come to mind. For the most part, these smaller gems in the RSA’s galleries are consciously restrained and beautifully detailed; ‘showing off’ isn’t an innate Scottish characteristic.

Indeed, the large proportion of Scotland’s 4,000 or so architects work in what’s known as micro-businesses, with long-standing portfolios of existing building conversions, residential work, extensions and modest-sized newbuild. By contrast, the schools and universities, larger scale housing and cultural buildings are executed by relatively few practices, who have broken through brutal procurement processes, which are in themselves worthy of another article.

Those who live on a diet of small projects are extremely unlikely to win work at any scale from the public sector, which is more dominant in Scotland than ‘down south’, with the effect that architectural practice has become polarised by size and type of work. There are no architectural practices based in Scotland that are larger than the conventional definition of SMEs (small and medium enterprises with fewer than 250 people) whilst, despite being just a small district within the London Borough of Islington, Clerkenwell’s architectural population could hardly be more different, with firms such as Zaha Hadid, Grimshaw, AHMM, Hawkins Brown, BDP and others all exceeding the SME threshold.

Compared to practising in Clerkenwell, though, there is no doubt that budgets and fees are lower, buildings are less lavish and it’s a much tougher economic environment in which architects can excel

The RSA’s annual exhibition, rarely covered by the architectural press, also has a broad selection of larger projects of course. The overall quality this year, thanks to curators Robin Webster and Ben Addy, was better than for some time, but the largest commercial schemes are noticeable by their absence. Frankly, this isn’t surprising as they tend to follow a predictable formula. It was especially disappointing recently to see an interesting contextual proposal by several local architects displaced, when the site changed hands, by Foster’s ubiquitous glassy offices for a big site in Edinburgh’s Haymarket.

The RSA, which celebrates its bicentenary next year, is by no means the only place to judge architecture in Scotland and the RIAS is to be commended for persevering with its annual get-together, something the RIBA abandoned many years ago. After years of restructuring, there is a sense that the RIAS ‘community’ is stronger than it was, but it is also much smaller than the RIBA, which makes it easier to know the key people and make a contribution.

However, the demise of the Lighthouse in Glasgow, funded with considerable ambition by the Lottery in the 1990s, means there is no longer a permanent venue for architectural debates, events and exhibitions. This needs to change and it’s a subject I’ll return to another time.

Another touchstone for architectural quality is awards, such as RIBA/RIAS and the schemes run by local chapters around the country. There are always some worthy winners that would hold up against other areas of the UK, for example by long-standing practices like Reiach & Hall, who have been shortlisted for three recent Stirling Prizes.

Compared to practising in Clerkenwell, though, there is no doubt that budgets and fees are lower, buildings are less lavish and it’s a much tougher economic environment in which architects can excel. It’s easy to see why London is such a magnet, particularly for young architects, but most departees return after a few years, such is the lure of the landscape and a particular quality of life.

Denise and I were drawn back to our home city of Edinburgh eventually, albeit Bennetts Associates has had a busy studio in Edinburgh for more than thirty years. It is the visits to Clerkenwell that are frequent now, rather than the other way round.

Postscript

Rab Bennetts co-founded Bennetts Associates in 1987 with his partner Denise Bennetts.

1 Readers' comment