Most architecture schools deny students the opportunity to study traditional design. It’s time for a radical change, writes Ruben Hanssen

It is no secret that architectural education has undergone dramatic transformations in the post-war years. Principles once perceived as commonplace were discarded, supplanted by the ideas of the Bauhaus and Le Corbusier. Craftsmanship was sidelined in favour of mass production, while stone, wood, and brick were replaced by concrete, glass, and steel.

However, there is a growing discontent with these prevailing architectural ideologies. An increasing number of people are championing new traditional architecture. Studies and polls, such as those by Create Streets and the Harris poll, reveal its popularity across a broad spectrum of the population.

Yet, there is often criticism from within mainstream architectural circles of architecture that seeks to revert to traditional design principles, and the architects who choose to practice in this way. It is labelled as ‘kitsch’, or ‘pastiche’ and accused of ‘historical falsification’.

But how justified is this criticism? There will always be a demand for traditional architecture, but universities are not teaching the techniques, principles, and skills needed to successfully produce it.

Thus, a clash exists: on one side, there is a strong demand from the market; on the other, there is no supply of architects who can meet this demand.

Additionally, there is a group of students who don’t feel at home designing Modernist architecture. Apart from courses in architectural history or electives in renovation & restoration, architecture faculties are currently not offering courses in how to design new traditional architecture.

And there is a long history of students who show an interest in traditional design being stigmatised and even failed, simply because they have diverged from the narrow path defined as acceptable by the architectural establishment. The respected and successful contemporary classicist, Robert Adam, endured precisely this treatment when a student at what is now the University of Westminster in the 1970s.

However, a movement is underway to bridge this gap.

In 2016, the first edition of a summer school in traditional and classical architecture was organised in the small Swedish town of Engelsberg, funded by the affluent Ax:son Johnson foundation. Graduates of this school would later join traditional architecture firms like Adam Architecture or find other avenues to support the cause of traditional architecture.

The summer school served as a sanctuary for misunderstood minds in a Modernist-dominated world. Engelsberg students forged life-long friendships and many felt, for the first time in their lives, a sense of belonging in an educational environment that respected and even fueled their appreciation for traditional design principles. Principles which they believe still hold immense value, and that still offer practical solutions for our modern world.

The Engelsberg summer school had its final year in 2019, but several other programmes have since embarked on a similar mission: to provide traditional architectural education based on hand-drawing, classical proportions, and designing with respect for local history and context.

We are denying a segment of our young architects the opportunity to realise their dreams

Even before Engelsberg, the organisation Premio Rafael Manzano in Spain had been organising a summer school since 2014, focused intensely on craftsmanship. In Belgium, La Table Ronde d’Architecture organises a summer school near Bruges, where students learn the secrets of Gothic architecture, with a strong emphasis on craftsmanship, involving visits to artisans specialising in stonemasonry, plasterwork, carpentry, and metalwork.

Additionally, in Utrecht another summer school was founded called ‘Let’s Build a Beautiful City’, focused on traditional urbanism. The school teaches students about designing attractive streets and squares with traditional urban fabric, combining New Urbanist principles with traditional architecture.

These schools operate autonomously, develop their own curricula, fly in lecturers, and secure their own funding, as they simply don’t have any other options. Most of them don’t have the luxury of big sponsors or their own accommodation and have to fend for themselves.

It is impressive work, and it seems the number of summer schools will continue to rise. For example, in Great Britain, Create Streets organised their first, shorter summer school this year.

I was involved with the Utrecht summer school and can share some insights. Firstly, the group of students is incredibly diverse, hailing from all continents, from Germany to India and from the United States to Albania. They come from various backgrounds and have different perspectives on society, but one theme is universal: they feel something is amiss with the way our buildings and cities are currently designed and often feel misunderstood in their architecture or planning studies.

Secondly, I can share that the students discover a newfound hope during these summer schools, finally finding a place where they can express their passion for architecture – a passion not nourished by the abstract and conceptual nature of modernism, but rather by the tangible, and the richness in detail inherent in traditional architecture.

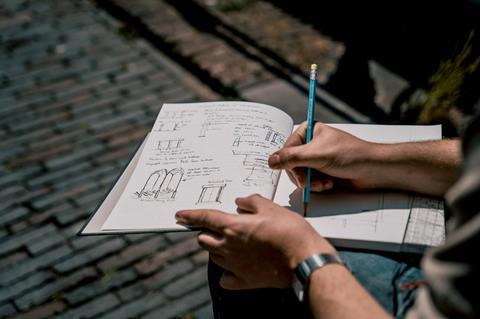

Finally, the students find themselves being encouraged to sketch by hand and to create watercolours. And they are liberated by being encouraged to embrace ornament – which has been fundamental to so many global architectural traditions throughout history – instead of being scorned for even contemplating it.

These personal experiences, and the rising number of summer schools, demonstrate an acute demand for this type of education, a demand that needs addressing. I believe universities bear a responsibility to, at the very least, offer an elective in traditional and classical architecture to accommodate the desires and inclinations of these students.

For as long as we do not educate architects to meet the market demand for traditional architecture, criticism of new traditional architecture will be unfair, because architectural education pitches the field against those who wish to practice in this way.

But more importantly: we are denying a segment of our young architects the opportunity to realise their dreams. And such a denial of aspiration is something we cannot allow to persist.

>> Also read: Eleanor Jolliffe talks to Robert Adam

>> Also read: Who’s it all for?

Postscript

Ruben Hanssen studied architecture and urbanism at the Technical University Delft before going on to found The Aesthetic City. He advocates for traditional approaches to architectural design and urbanism.

4 Readers' comments