The Italian capital is often desribed as a palimpsest. What can we learn from its layers of remembering and forgetting, asks Eleanor Jolliffe

I am a couple of weeks into my scholarship at the British School at Rome (BSR) and entirely enchanted by the city. Though the library at the BSR deserves a three month visit in itself I am spending a lot of my time walking the historic centre of Rome. So, for a few hours most days you will find me visiting churches and museums, hunting for fragments of medieval city fabric, trying to let it sink in – trying to understand what makes the city tick.

Rome, though it is a cliché to say it, is a palimpsest. Freud famously used the city’s layers as a metaphor to explain how human memory was structured. Arguably this is true of a lot of major European cities – but here the layers are on display in ways they just aren’t in, say, London.

I am reliably informed by my fellow researchers at the BSR, Drs Charlotte Mann and Ellen O’Gorman, that in ancient Rome to be forgotten was the worst thing that could happen to a person – “damnatio memoriae”. It was a punishment reserved for traitors and enemies of the Senate – the obliteration of the memory of a person’s existence, so that the world would be as if they never existed.

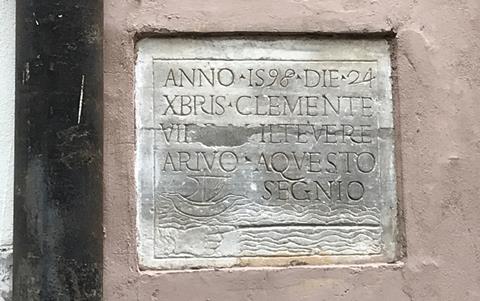

This concept seems to have sunk into the Roman psyche. When you know where to look, Rome is almost literally an open book. The walls, when you start looking, are covered with memories and plaques.

Some commemorate Roman imperial victories; some note flood levels and some tragedies. One, from 1723, requests locals not to turn the street into a “dunghill or muck heap”.

Elements of architecture act as memorials too – remnants of gateposts of the Jewish ghetto, Roman monuments reused as building materials for homes or churches to signal the classical pretensions to their medieval owners and patrons. Streets and parks are choked with statues and buildings inscribed with deeds of owners – apparently both real and imagined.

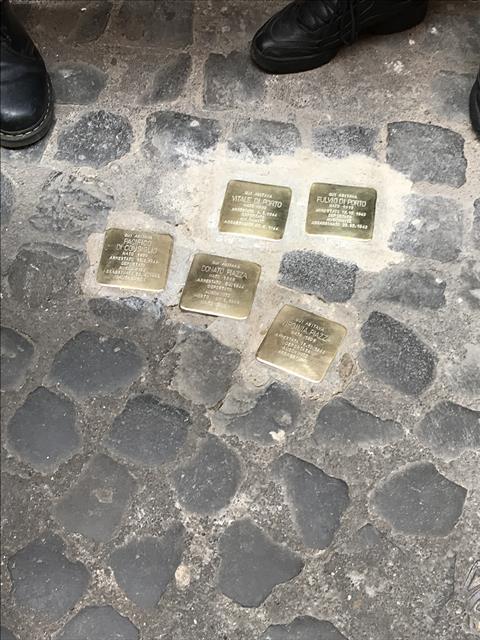

It continues today. Walking through the city last week we were given a guided tour of the Jewish quarter by Dr Luca Peretti, who is an associae fellow at the BSR. He pointed out en-route the new addition of the “Stolpersteines” – brass cobblestones that mark the homes of victims of the holocaust (a project that has moved across Europe from Germany – hence the German name).

It all begs the question though – in a location so continuously inhabited, who decides what is worthy of memorial, and what we have permission to forget?

Romans throughout history have ruthlessly reinvented their city, co-opting memories that suit them, obliterating those that don’t. At one site we visited this week, a Hadrianic villa was torn down for a Severan army barracks, which was destroyed for a Constantine cathedral, which was then heavily refurbished in the late 17th century. All the layers are still visible if you know where to look.

Several of the medieval towers I am studying were built directly over classical remains or incorporated classical fragments to appropriate the perceived greatness of the classical age to the medieval family in question.

The Fascist powers of the 1930s cleared acres of medieval and post medieval central Rome to create processional routes, “restoring” the classical monuments by removing the marks and sites of centuries of subsequent inhabitation. In order to cast themselves alongside the great rulers of Rome’s past the regime cleared centuries of inconvenient memories from Rome’s most significant sites.

We may be horrified now but will future historians think the same of our own statue toppling age? We also choose only to be reminded of the history that it suits us to be associated with.

Since the Second World War Italy has been more circumspect. Alessandro Alici, an Italian architect and academic has told me of the post war Italian restrictions, only recently loosening, on building at historic sites. Scarcely any new buildings have been allowed in the centre of Rome for decades (apocryphally I have heard just 147 buildings have been built in the Roman metropolitan area since 1945 but I don’t know if this is true).

Having spent days in what feels like a dreamscape wandering the streets of Rome, my emotional instincts tell me that this cautious approach to development is the correct strategy – modern life with its buildings and infrastructure can be left elsewhere. But the pragmatist in me, that also lives in the 21st century, recognises that such preservation is pushing modern life to the fringes.

To preserve in aspic risks “disneyfying” Italy’s historic cities – hollowing them out as historic tourist attractions, such as is happening most dramatically in Venice. To all intents and purposes such an approach to historic fabric leads to the slow, carefully concealed death of a city. There are no easy answers in this debate – which is being had as viscerally here as it is in the UK.

To memorialise is vital, and to have history as visible as it is in Rome is precious. This should be protected and celebrated. However, we must allow ourselves to forget some things – if only to leave some space for our own age. The question of what we are allowed to forget though, and who decides it… that is a trickier question to answer.

1 Readers' comment