Sarah Simpkin reports from Venice, where Carlo Ratti’s Biennale weaves together hands-on collaboration, ecological reflection and cross-disciplinary experimentation

Intelligens life in Venice

There’s an indecipherable network diagram across a long wall in the Giardini that tries to explain the organisation of the 2025 Venice Architecture Biennale. It charts the connections between the thousands of people involved. Caught in the middle of its web is chief curator Carlo Ratti, and his quote: “We want the projects to develop new knowledge, not just to showcase existing one.”

Ratti has been described as a polymath, preferable to claiming the title yourself. For the Biennale, he has drawn on his roles as architect, engineer, MIT professor and author to challenge the idea of the lone genius, to propose “a more inclusive authorship model, inspired by scientific research.” His title, splashed all over the city on vaporetti and posters, is the much-memed ‘Intelligens. Natural. Artificial. Collective.’ Getting through the next few days will take all three. It’s impossible to cover everything, but here’s what stood out.

Kingdom of Bahrain, 8 points; Finland, 10 points

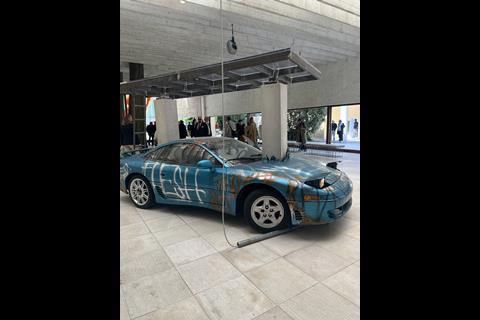

First, to the Giardini, where it’s hard not to be seduced by its permanent pavilions, sometimes at the expense of the exhibitions. I didn’t register why a car was impaled Cronenberg-style on concrete posts in Sverre Fehn’s Modernist slab of a Nordic pavilion, I was too busy looking at the roof.

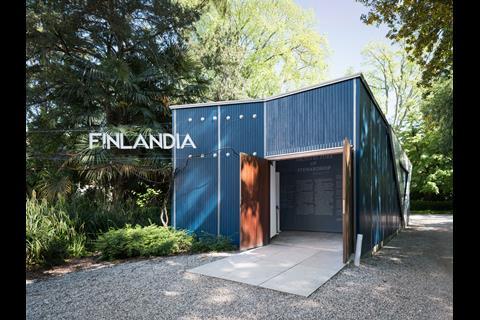

Finland’s atmospheric blue and white pavilion, built in 1956, is another beauty, but Alvar Aalto’s choice of wood for its construction has proved ill-suited to Venice’s humid lagoon climate. It survives through care. The exhibition takes this stewardship as its theme, projecting films that highlight the contribution of caretakers and maintenance workers to the making of architecture.

In the nearby Belgian pavilion, next to a biosphere of more than 200 plants, I find myself standing before a glass-fronted cabinet of flashing lights and circuitry. The presence of wires and so on tells me that this is technology, that the plants are doing something, and that something is being monitored. I’m aware that I’m observing knowledge. Perhaps, as Ratti hopes, I’m even watching the emergence of a new understanding of plants’ ability to moderate the indoor climate, but my participation is limited to enjoying a bit of a rest in its greenhouse.

Some of the more low-tech pavilions make an ecological point well for the less technically minded, like Lebanon, for example, upstairs in the Arsenale, by Collective for Architecture Lebanon. In The Land Remembers, wheat seed is cultivated in earth bricks to highlight how the rare biodiversity of Lebanon is under threat from conflict and climate change. Bahrain’s also feels useful and direct – a shelter for construction workers in a heatwave, a worthy winner of the Golden Lion.

Poland, 12 points

To engage meaningfully with the Biennale is to lurch from climate catastrophe to conflict to AI-driven futures, with a lot of soil and broken stone in between. It’s overwhelming. But some installations offer moments of clarity and humour. My personal favourite was Poland’s Lares and Penates, which explored rituals and beliefs. A smudge stick of sage to dispel bad energy was displayed with a fire extinguisher, each presented with equal status as a household deity. The wall was labelled a threshold “to separate the safe space from the unsafe area,” translating global anxieties into domestic symbolism. Conceptually clear and fun.

The Estonian pavilion, a corner building on the approach to the Giardini that has been partially clad in big white insulation panels, was also popular. So was Yasmeen Lari’s Community Centre, a temporary bamboo structure on the site of Qatar’s future pavilion. I had the chance to meet Lari, Pakistan’s first female architect, and we talked about the usefulness of hollow bamboo to channel cabling.

Elsewhere, I managed not to fall into the hole Denmark is digging in their pavilion. Balance is the theme for several countries: in Egypt, a giant see-saw table; in Spain, a room full of weighing scales expresses equity; and beyond the Giardini, Pakistan’s mobile of suspended rock salt.

Austria rebels with a conventional exhibition, Agency for Better Living. Refreshingly well-curated displays on housing in Vienna and the spatial challenges of Rome.

GBR, Geology of Britannic Repair

GBR, Geology of Britannic Repair (which gained a special mention from the jury) examines the intertwined legacies of architecture and colonisation in a collaboration between Nairobi-based Cave_bureau (Kabage Karanja and Stella Mutegi), Farrell Centre Director Owen Hopkins, and Kathryn Yusoff, Professor of Inhuman Geography at Queen Mary University.

Seeing it from afar from the other end of the Giardini’s axis, I thought it had been 3D point-mapped. Oh no, I thought, not another AI job. But up close, the dots become clay spheres, suspended in a veil around the building, puncturing its neo-classical pomp to evoke the traditional Kenyan Maasai manyatta.

That it addresses living history was made clear in the opening ceremony speeches. Karanja reminded us that co-curator Mutegi was absent in 2023 due to visa issues. He spoke about his grandfather’s internment in a colonial-era camp in the 1950s. “Our ancestors would be surprised to see us here, and also question, ‘What are you doing? Who do you think you are to be here, in terms of what we went through?’ But we are in a different time and space where we can talk about these difficulties, but it’s not easy […] but as a human species, we have to surround that. We have to come beyond our differences.”

The principle of the collaboration was set before the selection process began, as part of the British Council’s UK-Kenya Season 2025. I was interested in how the curators met, and asked Owen Hopkins. “Cave_bureau had given a lecture for the Farrell Centre,” he explained. “Kathryn Yusoff had written a catalogue for an exhibition they did at the Louisiana Museum. We came together around these loose connections and then thought about how we would balance the team’s disciplines.”

Could he relate it to his work in Newcastle? “Yes, in terms of the importance of architecture bringing together disciplines to shape the world positively… and to do that in a way that is inclusive and creates spaces where everyone is going to be welcome and supported, and feels that they have a voice in making.”

Like all participants, the team responded to the British Council’s public call. Before coming to Venice, I met Dr Helena Rivera of A Small Studio, whose Shared Grounds was one of four shortlisted proposals. They had also been shortlisted in 2023. “I wasn’t looking to reapply,” Rivera said. But a proposal came naturally from a project they had worked on in Nairobi.

Rivera and her collaborators proposed an 18-month knowledge exchange in Nairobi, an idea that seemed to align with Intelligens. It wasn’t intentional, she explained, since “when they release the tender, the overall curator isn’t known publicly.” The timeline creates a kind of chicken-and-egg dilemma. In practice, the larger national pavilions often do what they like, then retrofit their concepts slightly to the theme. Meanwhile, the Arsenale halls, with their robots and woodcarving demos, feel more in step with Ratti’s brief.

Of course, it wasn’t all reflections and research. There were celebrations for art, awards, whisky, even a drystone wall – no excuse too small to line up some trays of prosecco. I saw 2023 curator Lesley Lokko chair the reveal of a sculpture by Ben Dobbin of Foster + Partners for The Dalmore, and heard her express relief at enjoying the Biennale this time rather than curating it.

I had a peaceful half-hour sitting with friends on Norman Foster’s jetty, a collaboration with Porsche that probably cost a fortune, but was a simple pleasure in the chaos. Aside from Biennale events, I also saw the excellent show on Australian architect Harry Seidler at the new San Marco Art Centre, and got to meet architect Penelope Seidler – an experience worth the trip to Venice alone.

After the party

The Biennale has hosted 129 years of vernissage visitors and most are long gone. It’s a thought to put any single contribution in perspective, and I’m with Ratti on the need for less focus on individuals.

However, I didn’t see anything on barriers to collaboration, and the challenge is in converting all this thought into practice: not just showcasing interdisciplinarity, but fostering it. That begins with willingness to cooperate in the face of systems that privatise knowledge, against international forces, to overcome tensions and conflict, Brexit, tariffs… Problems an architecture event can’t solve, but the Biennale’s role as an international gathering still matters. It brings a fresh perspective on the world beyond the industry bubbles and a few reasons for hope.

On the way back to my hotel, I stumbled into the opening of the Cypriot pavilion, where a drystone wall was being built collectively. There were thanks for everyone, from embassy staff to artisans, and a plate piled with homemade éclairs. I was invited in for sweet wine. No humanoid AI. No egos. Just people sharing something useful, in an understated masterclass in how to build meaning together.

Postscript

Sarah Simpkin is a writer and communications consultant.

No comments yet