Alma-nac’s Design For All programme is helping to unlock community projects across the UK – and the team hopes to expand it further, writes Mary Richardson

Giving away design work is not unusual in architecture. Unpaid early-stage input is often the norm, particularly when practices are competing for commercial clients.

But for Alma-nac, the motivation has sometimes been different. From its early days setting up a market stall with a sign offering “Free architecture”, the practice has experimented with ways to make architectural thinking accessible to those who might not ordinarily seek it out.

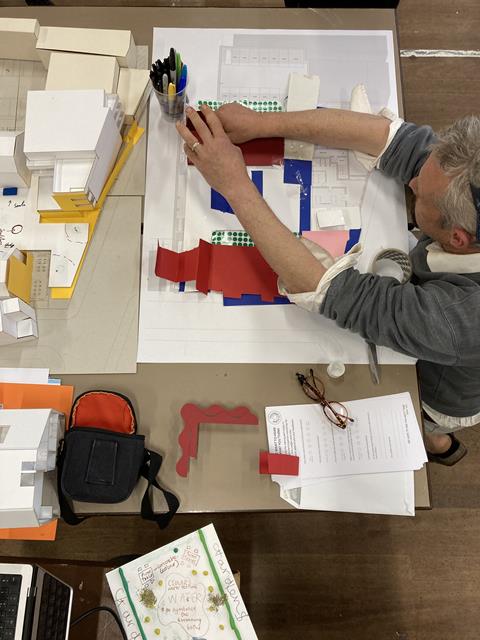

That ethos has now been channelled into a more structured initiative. In 2021, the team based in Waterloo, south London, launched Design For All, a scheme offering pro bono design advice to small charities and community groups. The idea was to offer early-stage support to organisations that often struggle to access professional services or get a project off the ground.

The scheme emerged from the kind of ad hoc work the firm had already been doing. Friends and acquaintances were increasingly getting in touch about projects for good causes, and the practice often found itself providing advice or sketches with no clear next steps. What was missing was a defined process, for both sides.

“We were happy to help,” says founding director Chris Bryant, “but there were always follow-up questions: ‘How much will it cost?’ ‘Do I get a sketch?’ ‘How do I take this forward?’ So, we decided to formalise the process by setting up what has become Design For All.”

Fellow founding director Tristan Wigfall says it was also about opening things up. “Formalising the process was also about wanting to be able to reach people who aren’t within our orbit, too. And extending the reach of our offer outside London.”

Helping projects take their first step

Each year, the practice invites applications from charities and grassroots organisations with turnovers of less than £1m. The focus is on the early stage of a project, often the most challenging to support financially. It is the moment when an idea is just beginning to take shape but needs a push to become credible in the eyes of backers and potential partners.

“We believe great spaces can facilitate great communities,” says Bryant. “So, through this scheme, we give advice on building projects at the earliest stages of development, because small charities often find that’s the hardest part of a project to fund.

“The winners get a pack of information which they can use to go and get proper funding, or take to their board and say, ‘Look, this is real! Let’s do a fundraiser’.”

The scheme has also helped Alma-nac to build a wider network of collaborators. “To make sure the chosen charities get all the help they need with their projects, we got some other specialists involved, too,” Bryant adds.

“We’re really lucky to have some excellent partners on board: structural engineers Simple Works; planning consultants NTA; Stockdale, who are quantity surveyors and project managers; OR Consulting Engineers; and decarbonisation and Passivhaus experts Beyond Carbon.”

The first few rounds of the programme have supported a varied group of organisations, often working with little infrastructure or experience in capital projects. In Toxteth, Liverpool, Alma-nac provided early-stage design advice for L8 Matters, a black-led community land trust aiming to transform the site of a disused swimming pool into a new community asset.

“They wanted to develop the site into a sustainable community,” says Bryant. “But, in order to be able to do that, they needed some help to produce a capacity study. That’s where we could help.

“We supported them to envision possible layouts, a programme, and brief for the site. And the work we did has enabled them to unlock the next £80,000 of funding for the project.”

Designing with what’s already there

Another recent recipient of support through Design For All was a Woodcraft Folk group in Herefordshire. Their project centres on a run-down holiday centre for young people overlooking the River Wye. The timber-framed building, full of character, was originally constructed with the help of YTS trainees, who made the cedar shingles that still cover the chalet-style structure.

“The Woodcraft Folk folk were convinced they needed to knock the whole thing down and rebuild,” says Bryant. “But we showed them how retrofit could work there.”

That shift in mindset reflects a wider trend among the groups applying to Design For All, many of whom are focused on repurposing what already exists rather than building from scratch. Sustainability has emerged as a consistent theme in the projects Alma-nac has supported, both as a funding imperative and a community value.

One such example is a proposal developed with the Royal Cornwall Hospital’s Charity in Truro. The charity sought help in turning an existing office building into accommodation for families of critically ill patients.

“It’s particularly needed,” says Bryant, “because the hospital serves such a large geographic area. The work we did showed them that their plans were feasible, and gave them the confidence to start fundraising for the centre.”

Growing the scheme

The Design For All programme is now open for 2025 applications. It is available to charities, community groups and similar organisations with a turnover under £1m and a viable building project that can be delivered sustainably. Further details are available on the practice’s website.

Alma-nac is also seeking partners and sponsors to help scale the initiative. “It’s frustrating because there are so many more projects we’d like to be able to help but can’t,” says founding director Caspar Rodgers. “But, with extra funding, we could extend the scope of the scheme. So, if anyone out there would like to get involved, please do get in touch.”

A ‘free market’ approach

The idea of managing pro bono work through a formalised scheme is in keeping with the resourceful, sometimes playful, way Alma-nac has approached many aspects of running a practice. That same attitude was evident when they were first starting out.

The firm was founded in 2009 by Rodgers, Wigfall and Bryant, and one of their earliest business development strategies was, quite literally, setting up a stall.

“We set up a market stall with a sign saying ‘Free architecture’ as a prompt to start conversations with members of the public,” says Bryant. “It was false advertising really, because, back then, we absolutely weren’t offering free architecture. But it started conversations…”

The trio were strategic in choosing their markets and, despite the occasional run-in with inspectors over unpaid pitch fees, the idea worked. “People came up to us with some really whacky ideas,” says Caspar. “One man said, ‘I’ve got 2,000 old tyres – what can I build with them?’ But other people had more sensible projects. And we got our first commissions from those market stalls.”

Reaching beyond the usual networks

Alma-nac’s early pro bono experiments, and their market stall beginnings, continue to inform how the practice engages with potential collaborators and clients. Their work frequently emerges from unconventional circumstances or informal encounters, often outside the usual procurement routes.

“We really like trying to find ways to talk to people who wouldn’t otherwise know where to find an architect, and people who aren’t in our network. That’s key,” says Tristan.

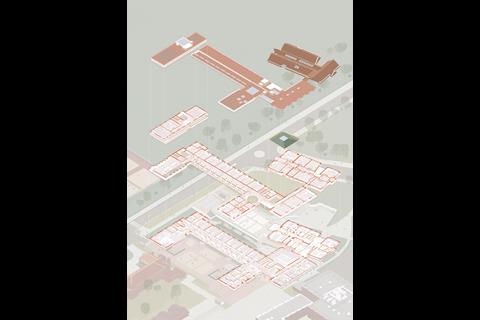

A current project at Dulwich College began not with a brief but with a conversation. The practice had been invited to deliver a series of workshops and ended up exhibiting student design ideas in a disused building. That set in motion a process that ultimately led to a significant new commission for the campus.

Tristan explains: “We became unofficial architects-in-residence there. The school wanted us to talk to students about what architects do, so we set up in a derelict boiler house and did workshops re-imagining how that space could be adapted.

“And that led to them saying, ‘We’ve got a masterplan for the campus, could you have a look at this bit?’ We thought it was going to be a toilet block or something, but it snowballed into a whole corner of the campus.”

The project that emerged is a new junior and lower-school building on the college’s imposing 19th-century site. Pupils have helped to shape the outcome, with some significant changes made in response to feedback. “The library was moved from the first floor to the ground floor due to pupil, and librarian, pressure,” says Bryant.

Environmental performance has been a key focus. “The school is working to make the whole site net zero by 2040,” Bryant adds. “We teamed up with Max Fordham engineers who are the net zero carbon consultants for this. And we’re seeking certification for it to be one of the new net zero carbon buildings.”

Expanding the brief

The Dulwich College project is not the only school-related work on the boards. In Suffolk, Alma-nac is working on a retrofit of Victorian school buildings to create a setting for children and young people with autism. The design incorporates biophilic principles and a palette of muted pastels to foster a calming atmosphere.

Alongside built work, the practice is also involved in strategic and communications projects. It is currently co-leading the pilot phase of a Department for Education programme focused on decarbonising school estates.

“It isn’t a built project, it’s a comms project that builds on a Safer Schools design manual we developed during the pandemic,” says Bryant. “We weren’t really sure we would be able to do it.” But the effort has resulted in a new resource to help schools begin the transition to lower carbon operations.

“There is, after all, a lot to be said for judicious winging it followed by frantic catch-up research,” he adds. “It’s a formula upon which many a successful enterprise has been built.”

Learning by doing

For a relatively small practice, Alma-nac’s portfolio is remarkably diverse. “We work across a wide range of sectors, which keeps things interesting because, to be honest, it means we’re always having to learn as we go. And that keeps you on your toes,” says Bryant.

Its private residential work includes a series of compact, idiosyncratic homes such as the Slim House, which measures just 2.3 metres wide, and others with equally evocative names: the Wedge House, the Split House, the Corner House, the House in the Woods and the Adaptable House, a prototype designed to accommodate the shifting needs of modern families.

Among these, the House within a House stands out for its clear concept and straightforward execution. “It was a fifties in-fill semi on a Victorian terraced street, built to fill a gap where a bomb had dropped in the War,” says Bryant.

“We extended it by ‘wrapping’ the existing mid-century house in a new contemporary brick form. Luckily, there were foundations that were strong enough to support the additional walls.

“So, we literally just put a new brick skin around the existing building, which is all still in there, and filled in the gap between the two walls with insulation. The walls vary in thickness depending on the distance between the new brick skin and the original walls.”

Bryant acknowledges that, as some critics have suggested, it might have been better to retain more of the original interior. Still, it is a deceptively simple, stylish idea. And the approach points to a a replicable “don’t move, improve” model for affordable, low-carbon extensions and energy upgrades that build on what is already there.

Another recent example of quick-impact work is the refurbishment of Tooting Works, a small-business incubator and co-working space. A modest paint job and a few carefully chosen moves helped the space to achieve a much stronger public profile.

“It’s been great for raising their profile,” says Bryant. “It seems like there’s not a day that goes by when they don’t have Sadiq Khan or some other politician down there using the place as a photoshoot location.”

Constraints as drivers

Bryant reflects on the benefits of working across different building types and sectors. “Working in lots of different sectors is one of the most enjoyable things about what we do,” he says. “A lot of our projects are challenging for us because it’s the first time we’ve done that kind of building – but that’s the joy of it.”

That unfamiliarity, he suggests, keeps the team sharp. “It means we can’t be lazy or complacent. We thrive on a challenge, and we have a strong process that involves being rigorous, interrogating the brief, and doing the research. And that creates the creativity, because we’re often starting from first principles rather than going, ‘OK, well we did one of these before so let’s just do that one again’.”

Rodgers points out that much of the team’s early experience came from working within tight limitations. “We cut our teeth on difficult, awkward projects,” he says, “projects that were squeezed in, or that were outside of the budget, or outside of the capacity for being delivered on small plots, or in strange sectors relative to their environment. And these constraints seem to generate creativity…”

That variety still defines their practice today. “One day we’re doing an animal hospital, the next an energy centre,” says Bryant. “It keeps things interesting.”

Infrastructure as public architecture

One of the more unexpected entries in Alma-nac’s portfolio is a new energy centre in Barking and Dagenham. Designed for the local council, the project will serve 10,000 homes via a district heating network and is intended to make infrastructure more legible to the public.

Nicknamed the “Pompidou of Barking and Dagenham”, the building expresses its engineering systems in full view and includes a visitor centre to explain how it works. “It’s part of the council’s mission to become the green capital of the capital,” says Caspar Rodgers. “We wanted to make a really expressive building that showed off what happens inside to anyone passing by, because it’s something to be proud of.”

For the practice, it represents another step into unfamiliar territory, expanding their repertoire with a new public-facing typology.

The project was won through a competition, a route the practice often uses to test ideas and build new partnerships. Another recent entry, for the 2024 Davidson Prize, took a more speculative turn. Alma-nac proposed reimagining Doncaster’s mothballed Robin Hood Airport as a co-living self-build community using repurposed aircraft components.

Among the ideas was a Boeing 777 fuselage repurposed as a roof. “It’s a fun, speculative proposal that combines sustainability with a playful lightness of touch,” says Bryant.

Not everyone agreed. “The comments on that one were, well…” he says, before trailing off with a wry smile, referencing the less-than-enthusiastic response in the Daily Express. Still, the team sees value in the process.

“Regardless, we see competitions as a good way to build relationships with new partners, engage consultants, test out ideas.”

Making space for ideas

That balance between playful experimentation and socially grounded ambition runs through much of Alma-nac’s work. Whether designing for co-living or net zero schools, small charities or major civic clients, the practice’s output is shaped by a belief that architecture should remain open and exploratory.

The practice blends serious intent with an energy that feels unusually light on its feet. That combination of purpose and playfulness is harder to achieve than it looks.

Maybe it is just that I have been reading about Abraham Maslow, but there is something psychologically healthy about their approach. Open, exploratory, occasionally chaotic – it feels like what a self-actualising practice might look like: motivated not by fear or ego, but by curiosity and growth.

No doubt, behind the scenes, it is sometimes seat-of-the-pants stuff. And it’s not easy to keep things fun as a practice grows. But, if anyone can manage it, I would bet on this lot.

And, if you happen to know a deserving cause in need of early-stage design support or some “free architecture”, they would like to hear from you. Applications to Design For All 2025 are open until 23 May.

No comments yet