As part of Building Design’s Designing Tomorrow’s Housing campaign, Ben Flatman visited HTA Design to hear how one of the UK’s most experienced housing practices is responding to today’s complex challenges

HTA Design is one of the UK’s most committed and experienced housing practices. Founded in 1969 with roots in the community architecture movement, it has spent more than half a century grappling with the realities of housing delivery, from estate regeneration to policymaking and post-occupancy evaluation. The practice has helped to shape national debates on housing quality, planning reform and procurement.

Its portfolio spans everything from temporary homes for people in emergency accommodation to high-rise, build-to-rent apartments and dense, mixed-tenure housing on tight urban sites. It embraces typological innovation and modular construction where these help to address real-world constraints. And it is vocal about the planning failures and short-term development models that the practice believes sometimes stand in the way of delivering more good quaity housing.

The practice’s work is often unshowy, but it is shaped by a clear sense of purpose: to create homes and places that work for the people who live in them. That clarity matters now more than ever.

In the face of a chronic housing shortage, a challenging planning system and a government commitment to delivering 1.5 million homes, HTA is one of the few practices with both the experience and credibility to speak across design and policy.

Its work offers a reminder that good housing at scale is not just about numbers, but about place, careful strategic thinking and the public good. And for HTA there is no shying away from the difficult decisions that confront the country in delivering more homes. While some architects avoid density and height, HTA confronts these issues head on.

From community architecture to LLP

The practice’s roots lie in the radical energy of late-1960s Camden. Founded as Hunt Thompson Associates in 1969, the firm was shaped early on by the spirt of the time.

“Community architecture is what it used to be called,” recalls non-executive chair Ben Derbyshire, who joined the firm as a Part 1 student in 1973 and has remained ever since.

The studio built a strong reputation in the field which it carries on into the present day. Derbyshire notes that, when Penguin published a guide to community architecture in 1986, it had HTA’s founding partner John Thompson on the cover, alongside the then Prince of Wales, an early advocate for community engagement.

The practice’s first home was a shopfront studio in Parkway, Camden Town. “Beautifully designed, actually, by John Thompson,” Derbyshire adds. But in those early years, engaging with communities in the design process was sometimes seen as controversial. “The processes were thought to be pioneering at the time, and in fact even opposed by the establishment as a kind of egregious abandonment of architectural responsibility,” observes Derbyshire.

The studio weathered internal divisions too. A split between founders Thompson and Bernard Hunt led Thompson to set up what would become JTP, taking a number of associates with him. “It is always a shock, that kind of thing,” Derbyshire says.

That early upheaval has not been mirrored in Derbyshire’s own trajectory. “I’ve had a slightly strange career of not having moved,” he adds. “The practice has moved around me and changed several times.” A second major transition came in 2013, when the practice restructured as HTA Design LLP.

Today, there are 12 full partners and several associate partners, with a gradual succession process constantly under way. “As colleagues like Ben are taking a step back ahead of retirement, we’re bringing in other people,” explains Sandy Morrison, partner and head of design. “And that seems to work quite well so far.”

Leadership perspectives

HTA’s evolution is reflected in its leadership. Each of the practice’s senior figures brings a different emphasis, shaped by personal experience and professional background.

Morrison has been with HTA for more than 25 years and, as well as leading design across all the studios, heads up the Edinburgh office. He returned to his hometown in 2007, setting up HTA’s first satellite studio.

“There are 40 folks in the Edinburgh office now,” he says. The team works on both Scottish and London-based projects. “We do some work there, and we do a lot of work in London from there.”

Morrison’s work is grounded in the act of drawing. He carries a sketchbook everywhere, draws in meetings, and his paintings even line the entrance lobby of the London studio. “Principally, I’m just here to draw and to paint,” he says, only half in jest. But his design leadership is threaded through the practice, helping to bind together its multidisciplinary approach.

Eleni Stathi, an associate partner and member of the RIBA expert advisory group on housing and planning, brings another perspective. She speaks of the value of working on regeneration projects where existing residents are living in poor and sometimes unsafe conditions.

“What first drew me to housing design was its immediate social impact. It’s one of the few forms of architecture that directly shapes people’s daily lives,” she explains.

“Coming from an underprivileged background, I’ve always felt that good housing design should reflect the real needs of the communities it serves, ensuring no one is left behind and that everyone feels seen and included.”

Derbyshire, a former RIBA president, connects the present practice to its political and professional heritage. He continues to write, campaign and advise on housing and planning policy, often acting as a bridge between the architectural profession and central government.

He speaks candidly about the need for long-term stewardship models and better oversight of quality. “There’s a very, very big deficit in the skill and expertise necessary to create these places,” he says, of the government’s ambitious housing targets. “Apart from finance, that’s probably the biggest challenge.”

Between them, Morrison, Stathi and Derbyshire embody the intellectual and ethical range of HTA. Design, public service and critical advocacy all have a place in how the practice sees its work.

Multidisciplinary design

HTA began with a focus only on architecture but, over time, recognised that designing good housing in isolation was not enough. “We were just architects at first, but we realised you can’t create great places for people to live if that’s all you are,” says Morrison.

“So we brought in landscape architects. Since then, we’ve added the other disciplines one by one.”

Today, the practice brings together architecture, landscape, planning, urban design, building physics, interior design and graphic design, with each discipline led by a dedicated head. “My job is to help put all that together,” explains Morrison.

To stay abreast of what clients need, the practice is constantly assessing where resources can be best allocated. The graphics team, once focused on visualisation and branding, has moved into supporting consultation work and communication.

“Graphic design has evolved,” Morrison says. “It has shifted much more into engagement. Engagement has become huge.”

Stathi points to the way this multidisciplinary set-up supports placemaking in its broadest sense, highlighting how HTA’s interiors work goes beyond conventional fit-out and finishes. It involves thinking carefully about how people move through buildings, how they find their way intuitively, and how layout and signage can support a sense of ease and orientation from the outset.

“We’re doing interiors, but also thinking about wayfinding from the start. It’s about the full experience,” she says.

The result is a layered approach that sees housing not just as individual units or objects in the townscape, but as part of a wider public realm. It reflects a belief that quality placemaking depends on how people move through, use and feel about their surroundings and on having the right tools in place to shape those experiences.

Embedded values: sustainability and research-led design

HTA’s Hackney Wick studio, into which the firm moved in 2023, is housed in a reconfigured Victorian warehouse. The building is a live case study in how to design and retrofit for long-term performance.

“It’s like an old building, but actually, because of the thermal capabilities, it’s very modern,” says Morrison. “It sets up a relatively constant temperature […] it’s got lots of thermal mass. Every single internal wall is solid.”

HTA acted as both client and architect. “Being the client was an interesting experience,” says Morrison, explaining how commercial and practical considerations informed the design. “It does make you consider different choices from what you would advise another client to do.”

>> Also read: HTA transforms Victorian warehouse into its new studio

The practice decided not to insulate some external walls and embrace the existing building’s thermal mass. “If we were working with a client, it would be expected to say ‘you really need to do that’. But actually, acting as client, we decided not to do it,” Morrison admits.

For Stathi, the space is also a site of ongoing research. “We’re able to collect data about the performance of this building,” she says. “So, when we are having conversations about PVs […] we have got this data about our energy performance.”

It is a building from which the team at HTA is constantly learning – and it helps to shape the advice they give to others.

Housing first

HTA’s work is almost entirely focused on housing. “Ninety per cent of it,” says Morrison. “Places for people to live is what we want to do.”

That covers everything from high-rise modular towers to low-rise council homes. “We cover all areas of housing and typologies in the public and private sectors,” Morrison explains. “We’re happy to do the large-scale build-to-rent buildings […] and the temporary affordable housing that we’re doing with Wates.”

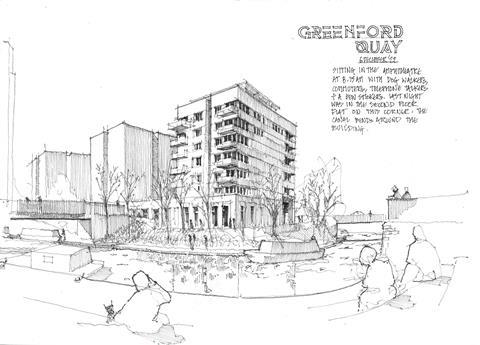

One of HTA’s most high-profile developments, Greenford Quay in Ealing, reflects the complex trade-offs behind large-scale urban intensification. “It’s around 80% single aspect,” says Morrison. He acknowledges that, for many designers, this would be a point of concern. But Greenford Quay works, he says, because it offers something different. “The general feel of the space is great. It’s got a spacious public square and the canal running through it. It’s not like everything else.”

Stathi recalls the early conversations on Greenford Quay. “We controlled the canal frontage,” she says. “We thought, let’s include all that space in the public realm and create something really meaningful in terms of this being somewhere people want to be and to spend their time.”

For Stathi, the quality of the public realm helped to anchor the project and justify the taller buildings on the site. “That place became a destination in itself, a context in itself.”

HTA has not shied away from tall buildings either and Derbyshire is candid about the pressures that drive them. “Tall buildings have been built all over London, and locals sometimes don’t like it. And I share some of their disquiet,” he told a panel at UKREiiF last year. But he is clear-eyed about the challenges of delivering much needed new housing in urban areas.

“The reasons why we work for clients who design tall buildings are the land values, the absence of land in cities, and the business model with which affordable housing is delivered.” This pragmatism underlies HTA’s wider approach, which seeks to address the world as it is, and to deal with asssociated planning and viability constraints head on.

Temporary housing with Wates

HTA’s housing output is shaped by these complex realities. But it is also defined by careful typological thinking.

HTA’s pilot scheme of modular homes in Romford, delivered with Wates Residential, reflects its ability to think pragmatically while upholding design standards. “We’re doing a project now with Wates,” explains Morrison. “It is a great idea because it takes people out of the Premier Inn that they are in and gives them a compact, functioning home.”

The scheme provides 18 homes on a regeneration site that will eventually be redeveloped in a later phase. The key idea is delivering flexible “meanwhile” homes on sites as they are built out.

“They are smaller than standard affordable housing,” Morrison says. “But it’s a big improvement on keeping people in hotels, where multiple family members are sharing one room.”

The units are relocatable and designed to be easily demounted and reused elsewhere. “We’re working on a site that will eventually reach permanent development. Then, the temporary modular homes will get moved on to a new site, and so on,” Morrison explains.

Importantly, they are not stop-gaps with compromised dignity. “We designed these to be family homes, large enough to accommodate separate living, sleeping and washing facilities with an area of private, external amenity space,” says Morrison.

For Derbyshire, the scheme represents more than emergency provision. “It’s not just building [prefabs] and then scrapping them,” he says. “It’s about maximising the social value in those projects.”

Delivery challenges

The HTA team’s frustrations with the constraints on the housing system surface repeatedly during the conversation with Building Design. From inflexible masterplans to viability issues, the consensus was clear – too much is being asked of schemes too early, in a way that cannot respond to market shifts or emerging challenges.

Derbyshire points to Enfield council’s Meridian Water scheme adjacent to the Lea Valley Regional Park, which HTA is working on as masterplanner, to illustrate his point about the need for masterplans which can evolve. “It’s a classic example of a tightly drawn masterplan and design code,” he says. “It has faced viability challenges due to changes in the market and supply chain costs, which has meant we’ve had to rethink our approach.”

Morrison agrees. “If people are not just rushing to build a development out, then what are our next steps? How do we approach these challenges thoughtfully while remaining faithful to the overall ambitiion and intent?”

For Derbyshire, flexibility in the masterplan and placemaking vision is essential. “The question is, how do you define the essence of something that will survive those changes and still produce the quality outcome?”

The team describe the kinds of planning policies that ignore local conditions and leave little room for genuine engagement or evolving needs. Morrison says: “We used to work on masterplans where, effectively, what you were trying to do was create a sort of straightjacket. Now people are thinking much more in terms of long-term strategies.”

The team also questions the government’s renewed emphasis on new towns, calling instead for a greater focus on existing places. “It has a distinct jam tomorrow flavour,” says Derbyshire of the new town’s taskforce search for suitable sites for 10,000-home new settlements. “We haven’t even finished the last designated new towns. They all need densification, like most cities need densification.”

Looking ahead

For HTA, the path forward is about remaining grounded in the belief that housing is a public good. “We have a job to do,” says Stathi. “The government is clearly very keen on building new housing, and we are really best placed to do that.

“The types of projects that I work on are regeneration projects with existing residents that live in substandard accommodation. Living in a house that is healthy and doesn’t make you sick is very, very important.”

Stathi sees the current moment not just as a challenge, but as a time for collaboration and building capacity. “There’s a lot of upskilling that needs to happen in our industry in general. And we also need to be innovative. Sometimes these are the times when we need to figure out how to solve the puzzle in a slightly different way.”

Derbyshire has been campaigning for a renewed focus on housing quality. Working with peers in the House of Lords and across the sector, he wants to see new models of investment and delivery.

“Speculative housing is so often a pillage, left with poor management and maintenance so that a spirit of place never develops,” he says. What is needed, he argues, is “long-term patient investment” that puts stewardship and social value ahead of short-term return.

Places where people want to live

HTA has remained active for more than 50 years by adapting to changing political and economic conditions without abandoning its core focus. “We do everything in terms of housing,” says Sandy Morrison. “But the purpose of the business is places for people to live, where they want to live.”

That clarity of mission has given the practice a consistent identity, even as debates around housing policy and delivery have grown increasingly polarised.

In the absence of clear leadership on quality from central government, HTA has continued to engage with the complexities of housing delivery on its own terms. Its work reflects an ongoing attempt to navigate conflicting demands between design quality and cost, short-term outcomes and long-term value.

The practice’s projects highlight the compromises and trade-offs that define contemporary housing development in the UK. Its contribution is perhaps best understood not just in terms of its built projects but in the questions it raises about how housing is planned, financed and sustained over time.

Through its multidisciplinary model and steady engagement with housing in all its forms, HTA provides a case study in what can be achieved within the sector’s current constraints. It also offers a clear vision for how housing delivery might be improved, if the political will can be found to support it.

The housing brief: embedding design in national delivery

Housing is an undeniable priority for the UK with renewed government focus putting it at the top of the agenda - but he big question is how do we ensure quality while driving for quantity?

Building Design’s new campaign Designing Tomorrow’s Housing will investigate how the delivery of 1.5 million new homes can be reconciled with maintaining high design standards.

Rather than simply reporting on figures and planning reforms, this campaign will delve into the challenges and opportunities of integrating exceptional design, robust planning standards, and sustainable placemaking into the mass housebuilding process.

We know that design and housing professionals come up against these issues in their everyday working lives, which is why we want to hear from you - our readers - about your experiences.

Postscript

No comments yet