An uncompromising critic of modernism and passionate advocate for traditional urbanism, Krier reshaped architectural debate through his writings, teaching and the enduring influence of projects such as Poundbury

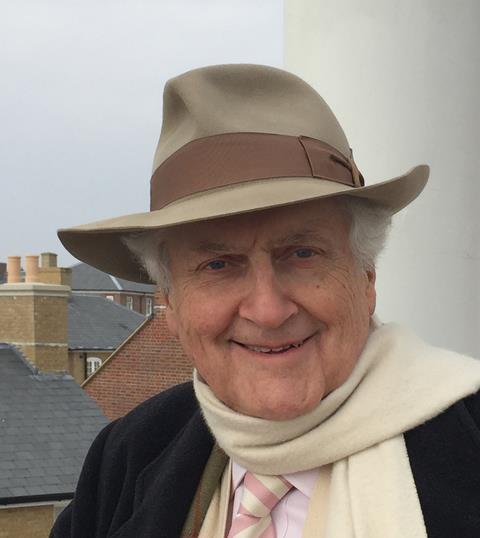

Léon Krier, one of the most influential and controversial architectural thinkers of the past 50 years, and a former BD columnist, has died at the age of 79.

A committed traditionalist and leading figure in the new urbanism movement, Krier was best known for his long-running collaboration with King Charles III and for his contributions to Poundbury, the much-debated urban extension to Dorchester, in Dorset.

Born in Luxembourg in 1946, Krier trained briefly in Stuttgart before abandoning his formal studies and joining James Stirling’s London practice. He later taught at the Architectural Association and the Royal College of Art, where he became known for his critiques of modernism and his belief in the civic value of traditional architecture.

Krier’s early career saw him developing his ideas through writing, drawing and teaching rather than built work. It was during this early phase that he coined the phrase: “I don’t build because I am an architect.” This became emblematic of his rejection of what he saw as the aesthetic and ethical compromises required by mainstream modernist practice.

Rather than simply critiquing the dominant architectural culture, Krier’s refusal to build was framed as a principled act, a rebuke to a profession he believed had become enthralled by ideology and spectacle, producing what he later described as “junk” buildings in the service of political or commercial ends. His comment was also a nod to a longer intellectual tradition in which architects concerned with meaning, form and civic responsibility often built relatively little.

Later in his career, however, Krier became increasingly associated with realised projects, most notably the masterplanning of Poundbury, where he attempted to give architectural form to the human-scaled, mixed-use ideals he had long championed. While not all elements of the town were designed by him, it remains one of the most tangible embodiments of his philosophy and the principles he shared with his patron, the former Prince of Wales – now Charles III.

Though widely derided in the architectural mainstream for what many saw as a backward-looking and conservative worldview, Krier was also deeply influential. His thinking helped to shape the new urbanism movement and his critique of functional zoning and modernist city planning played a part in shifting professional consensus away from high-modernist urbanism towards a more street-based and public-realm-focused approach.

Today, even architects who reject the classical language often work within the kind of walkable, mixed-use urban forms that Krier argued for from the 1970s onwards.

Arguably his greatest influence has been in urbanism and planning, where the rejection of the modernist model of vast housing estates, megastructures and zoning has become widespread. While Krier often found modern attempts at traditional placemaking inadequate, his advocacy for streets, squares and buildings that engage the pedestrian gaze helped to lay the foundations for a new orthodoxy of human-scale development.

Among his best-known built projects are the Jorge M Pérez Architecture Center in Miami, the Village Hall in Windsor, Florida, and his work on Ciudad Cayalá, a controversial exclsuive enclave in Guatamala City. He also contributed to the Seaside development in Florida and advised on the Nansledan urban extension to Newquay in Cornwall. The Krier House in Seaside remains the only project he claimed was realised entirely to his vision.

Krier also took part in the inaugural Venice Architecture Biennale in 1980, contributing a stripped classical façade to the Strada Novissima, the centrepiece of the exhibition The Presence of the Past. The Biennale is widely seen as a pivotal moment in the rise of postmodernist architecture and helped bring Krier’s ideas to wider attention. Although often associated with the movement, he remained sceptical of postmodernism.

In a 2024 interview in the Daily Telegraph, Krier reflected on his work at Poundbury, the experimental town he designed for the Duchy of Cornwall, which became one of the most high-profile examples of traditionalist urbanism in the UK. The project was widely ridiculed by mainstream commentators in its early years.

“They thundered that it was a fantasy of the prince,” he recalled. “They could not applaud a traditional project for reasons of principle, whatever its qualities or success.”

But, he claimed, those predictions were confounded. “Immediately, it worked,” Krier insisted, describing how the town attracted people from a mix of backgrounds and proved viable as a functioning place, not just a symbolic gesture. He dismissed criticisms of Poundbury as elitist or sterile, arguing instead that its success lay in demonstrating what one determined client could achieve by resisting corporate development models.

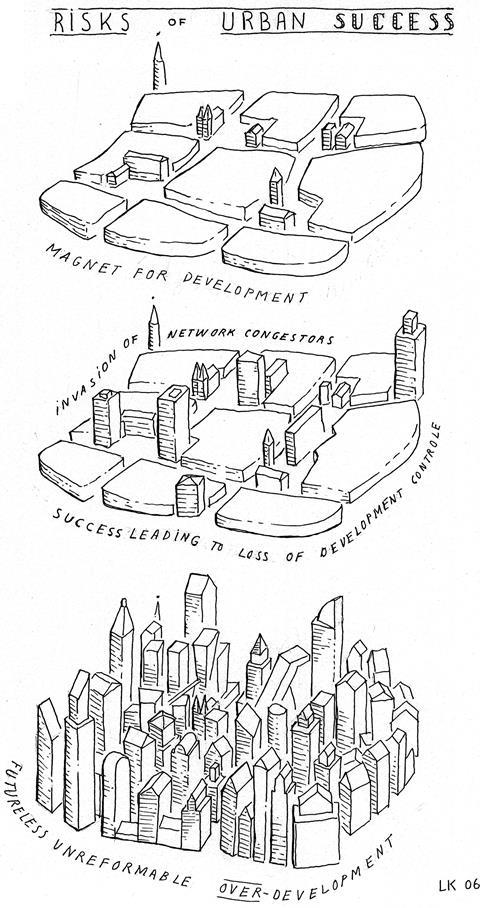

Though often polarising, Krier’s views were not entirely dismissed by modernist architects, some of whom shared his scepticism about the legacy of post-war urbanism. In a 2017 column for BD, he launched a full-throated attack on the proliferation of high-rise buildings in London, warning that the capital’s historic infrastructure could not withstand the strain. He argued that the city’s transport and public realm systems were being overwhelmed by a planning culture fixated on density at all costs.

“A metropolitan network of streets, squares, rail-tracks, and parks conceived to house an urban fabric of walkable building heights cannot host large amounts of utilitarian high-rises without causing irreparable damage to its long-term viability,” he wrote. The piece reflected his wider concern that London was being reshaped by economic and political pressures rather than coherent planning or civic values. He believed this shift represented an abdication of professional responsibility by architects and planners alike.

Krier was also unafraid to enter controversial territory. His admiration for the architectural language of Albert Speer, which he argued could be separated from the ideology of the regime Speer served, attracted lasting criticism.

In 2024 he told the the Telegraph: “Absurdly, it’s always traditional architecture that is associated with Hitler, Stalin and Mussolini… But Hitler also built gigantic modernist buildings – why were they not forbidden?”

Despite this, his ideas attracted a broad international following and helped to shift the debate on how cities should grow.

Krier remained a regular contributor to debates about urbanism well into his later years. He continued to work on the final phases of Poundbury and remained close to the now king, who had appointed him as an advisor on architecture and planning in the 1980s. The two shared a belief in architecture’s civic responsibility, and in the potential for tradition to offer not only continuity, but solutions.

His older brother, Rob Krier, born in 1938, was also an influential architect and urban theorist, and died in November 2023. Krier shared the following words with BD about his brother following his death: “To have grown up next to the volcanic talent was fuel for life, so for me he remains more than alive.”

Krier’s influence persists in contemporary masterplanning, and his legacy is visible in the broad revival of interest in human-scaled urbanism. Though architects continue to disagree about his aesthetics and politics, there is no disputing that Krier changed the architectural conversation – and made it impossible to ignore the enduring appeal of the traditional city.

>> Also read: Rob Krier dies, aged 85

>> Also read: It doesn’t matter if skyscrapers are designed by world-class architects or hacks – they’re destroying our cities

Postscript

No comments yet