The practice’s chief executive talks to Tom Lowe about the government’s decision on a third Heathrow runway, the impact of Rachel Reeves’ tax policies on business and how the practice has managed to survive for a remarkable 115 years

Scott Brownrigg recently celebrated its 115th anniversary, an impressive achievement not just for the architecture profession but for the construction industry as a whole. The firm has survived two world wars, 11 recessions, a near collapse in the 1990s and, most recently, the covid pandemic. This heritage gives it a legitimate claim to be the guardian of one of the most venerable brands in the built environment sector.

Last autumn, the practice launched a new book, Scott Brownrigg: Architecture + Progression, charting the history of the practice and offering a few words of advice on how to maintain a business into its 12th decade. In his speech to 200 guests from across the industry at the book’s buzzy launch party in Fitzrovia, the firm’s chief executive Darren Comber spoke of the secret of enduring success as being “proactive rather than reactive” in the face of constant change.

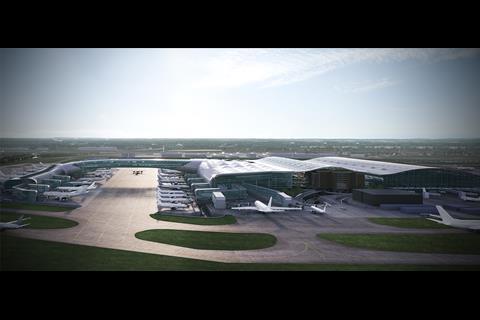

Comber stood on the stage next to the man who had introduced him, Surinder Arora, the billionaire hotel magnate who had appointed Scott Brownrigg to design a £25bn alternative to Heathrow airport’s third runway expansion. At the time of the book launch, the government was in the final stages of deliberation between the proposal and the airport’s own more expensive £49bn scheme, which featured a longer runway.

The project would have marked a symbolic return for Scott Brownrigg to the site which had launched its heyday in the 1980s, when it was the second biggest practice in the UK behind BDP. That decade saw a string of high-profile civic infrastructure projects, starting with Heathrow Terminal 4, completed in 1986, to Manchester airport Terminal 2 in 1989 and the BBC White City broadcast centre in 1990.

It was not to be. At the end of November, the government announced it had picked the more expensive version, despite concerns over the disruption which will be caused by the need to reroute the M25 to accommodate the scheme’s 3.5km runway.

Building Design sat down with Comber at Scott Brownrigg’s London headquarters in Covent Garden about four hours after the decision was announced. It is fair to say that the 52-year-old was somewhat frustrated by the government’s choice. There have been promises, including from Rachel Reeves, that taxpayers will not foot the bill for the expansion, a claim which Comber describes as “complete nonsense”.

“Every time you fly, you’re going to be paying,” he says. “It’s yet one more government stealth tax.”

Then there is the issue of the disruption caused by the construction of the longer runway, a factor which Comber suggests the government has minimised out of political expediency. “The fact that, for the next 10 years, you and I are not going to be able to drive around the M25 [without disruption] – no one cares about that because this government won’t actually have to address that.”

For Comber, the decision feeds into his wider frustration with the government and what he sees as Reeves’ lack of appreciation for what motivates businesses to invest. He is speaking the day before the autumn Budget, which included an extension of the freeze on national insurance and income tax by three years to 2031, coming on top of the 1.2% hike in employers’ national insurance contributions announced last year.

“If we see any more increases in national insurance and income tax, then it’s going to be quite problematic for everybody,” Comber says. “But specifically for us as a business, that will impact everybody.

“Obviously people want to get paid more, but we won’t have the funds to actually pay people more, because your margins will get slimmer and slimmer.”

Comber’s comments belie the fact that the practice has actually been doing relatively well in recent years. It was the third most profitable practice in the UK last year, while its turnover increased by 29% compared to the previous 12 months, from £21.7m to £27.9m.

We need to see incentives for us to invest in the UK and do our work in the UK

Much of this was driven by a near five-fold increase in its turnover outside of Europe, which rose from £2.4m to £11.5m.

Closer to home, the practice was a little less successful, with revenues falling from £17.6m to £15.8m in the UK and from £1.6m to £630,000 in Europe. Comber sees the figures partly as a result of a more investment-friendly business environment overseas.

“We need to see incentives for us to invest in the UK and do our work in the UK,” he says. “Because ask yourself, why are we doing 50% of our work overseas now, and we’re taking our talents elsewhere? Because the UK has done nothing to support us.”

Growth story

The origins of Scott Brownrigg can be traced back to the firm founded by 28-year-old Annesley Harold Brownrigg in 1910. From 1918, after serving in the First World War as a major in the Royal Garrison Artillery, Brownrigg joined up with another architect, Leslie Hiscock, and started to expand the practice from its base in Guildford.

The firm grew in size over the following decades, adding Turner to its name in 1946 and finally Scott in 1958 to form Scott Brownrigg and Turner, becoming known later as SBT.

At its height in the 1980s, SBT employed 400 people. Its decline, caused by a combination of the early 1990s recession and a quick succession of retiring partners taking money out of the business, was precipitous.

By 1995, when Comber joined as an entry-level architect, its staff count had plummeted to just 45 and it was in £3m debt, equivalent to £6.2m in 2025 prices. On the Friday of the week that he started, the practice received a letter from the bank threatening to shut the business down. The firm only survived because it had a job in Abu Dhabi on the artificial Al Lulu Island which had a £2m fee.

“So, we went to the bank and said, look, if you shut us down, we’ve got this £2m fee.You’re going to get nothing because there’s no money to take. Or you let us trade out of it, and you get your money,” Comber recalls. “And that’s what the bank did. And so the rest is history.”

Rebuilding process

The practice was lucky to have an esteemed brand on which to rebuild, although that came with complications. In the early days, the firm’s remaining staff went to great lengths to conceal its diminished size in an industry which assumed that it was still a behemoth, often resorting to drafting in friends to fill up the office when clients came to visit.

“We had like five people, but people thought we were like 500 still,” Comber remembers. “I would ring up my friends and say ‘what are you doing this afternoon. Are you close by?’ … So we would literally fill it up with people.

“Clients would go, ‘it’s really busy isn’t it, your office’. And we’d go, ‘yeah, normally it’s busier than this, but everyone’s at lunch’.”

Despite the staff being untroubled by the prospect of a pay rise during the lean years, Comber stuck at it. Was he ever tempted to leave? “I liked the people I worked with,” he says.

“We all had a common goal, and we thought, do you know what? We’ve got a brand that was once something. It’s now not. We’ve got a real opportunity to turn that brand into a global brand again. So it was kind of exciting for us”.

The more he invested himself in the business, the more he felt he had personally created and the less he wanted to leave. Comber says he never felt a strong urge to set up his own practice with his name above the door: “I never had that sort of sense that that was my calling. I didn’t have that ego,” he adds.

At the age of 27, five years after joining SBT, Comber became the youngest ever member of the firm’s board. A decade later he was chief executive, a job which he says he was only offered because nobody else wanted to do it.

It was 2011 and, by this time, the firm’s position had improved, with around 200 staff now on the payroll. But, with the recession in full swing, everyone knew the chief executive job would involve difficult decisions on redundancies. “At those sorts of times, you are literally no one’s friend,” Comber recalls.

We’re big enough to compete with the biggest and best in the world, yet we’re not so big that it’s kind of like, get another project, chuck it on the fire

If readers of Scott Brownrigg’s new book are wondering why the practice chose to commemorate its 115th year rather than, say, the more obvious figure of 100 years, it is because “no one had the appetite for it” in 2010. Plans to mark the 110th anniversary were derailed by covid, and were not revived until two years ago, when the practice started to put together materials for the weighty 239-page hardback, which tells the story of the practice from its founding to the modern day, including its plans for Heathrow with Arora Group.

The practice now employs around 200 people across eight offices, four in the UK – in London, Guildford, Cardiff and Edinburgh – and four overseas, in New York, Singapore, Riyadh and Amsterdam. Its biggest sectors in recent years have included life sciences, with the practice securing planning approval for a string of laboratory projects across the Oxford-Cambridge arc including a £150m scheme at Oxford Science Park. Its biggest growth sectors include data centres, central to the AI boom, and advanced tech schemes including hydroponic towers for vertical farming.

Where does Comber see the practice going in the next 10 years? He is reluctant to drive too much growth, preferring to keep the practice closer to what he describes as its £30m turnover “sweet spot”.

“We don’t feel that we need to be in a position where we’ve got to be 1,000-strong to go up against some of the big American corporates,” he says.

Comber says his experiences of working in the practice at times when it has been bigger have not always been positive. “You take work which sometimes you don’t really want, because you know that you have just got to keep feeding the machine. We don’t want to be like that.”

“We’re quite happy with where we are. We’re big enough to compete with the biggest and best in the world, yet we’re not so big that it’s kind of like, get another project, chuck it on the fire.”

After the the firm’s seesawing fortunes over the previous three decades, an experience which Comber describes as being like working for “five or six different practices”, he is now appreciating a bit of stability. “We’re planing now,” he says, comparing the practice in its current state to a speed boat.

“We’ve got out of the choppy water and we’re doing some really lovely things. And we’re enjoying it like, ‘wow, this feels so much better’.”

No comments yet