A Cambridge college seeks to revitalise its historic buildings while respecting tradition and heritage, writes Ben Flatman

To many visitors, the historic core of Cambridge remains seemingly unchanging. Dominated by university and college buildings, the city sometimes feels reminiscent of an open air museum. But, while undeniably beautiful, this world of hushed cloisters and manicured lawns can also appear off-putting or even stultifying to some.

Finding the balance between maintaining their traditions while ensuring that the ancient quadrangles remain vibrant and living spaces is an on-going challenge for the colleges. Many have sought to create more up to date amenities that they hope will appeal to new and more diverse audiences.

But sites for new development are usually extremely constrained, requiring ever greater ingenuity from architects looking to provide modern facilities for interaction, collaboration and outreach.

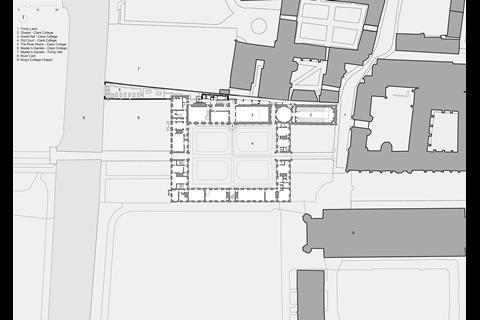

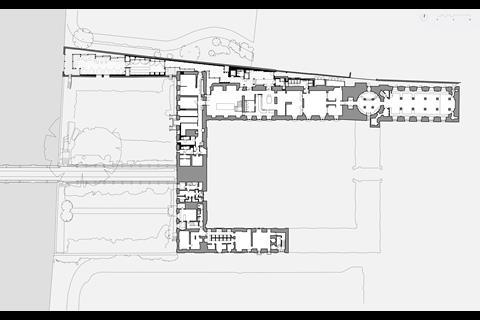

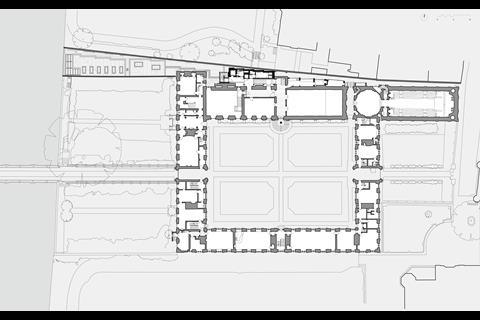

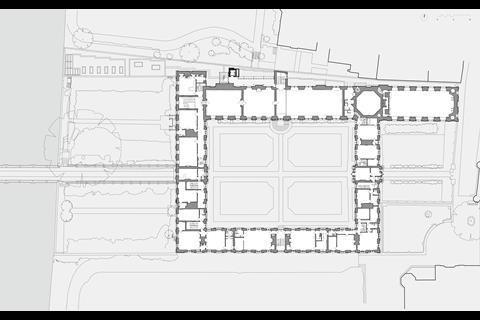

Witherford Watson Mann’s recently completed River Wing seeks to carve out just such a niche from a slither of land along the northern edge of Clare College’s Old Court. The last major addition to Old Court was in 1785, when the chapel was added. River Wing has been slipped into the narrow wedge that runs eastwards from the banks of the Cam towards the chapel.

Once occupied by ancillary spaces and a single-storey office block, this barely viable site sits between the chimneys and gables of the kitchens and master’s lodge on the north side of the college, and the south wall of neighbouring Trinity Hall’s fellows’ gardens.

A collage of different problems

Witherford Watson Mann was first appointed by the college in 2014. Phase one addressed the historic fabric of Old Court, with extensive refurbishment of existing rooms and upgrades to electrical systems and accommodation.

The practice’s original brief for phase two was made up of a series of disparate elements. The college wanted improved disabled access, refurbished kitchens, better circulation and a new fire escape from the student accommodation on the top floor.

“It wasn’t a very aspirational brief,” says practice director Simon Witherford. “It read like a kind of collage of different practical problems.”

He adds: “The one slightly more aspirational element was the requirement for a new café. The college wanted a non-hierarchical kind of space for everyone in the college community – staff, students and fellows – to be able to get a coffee and to work in.

“We went through a series of iterations and, through that process, we eventually decided to use this sliver of land between the north face of Old Court and the boundary wall with Trinity Hall.”

“What it’s also doing is serving the historic rooms in Old Court to function much better,” says Witherford. “So, it’s very much a subordinate intervention.”

The intervention

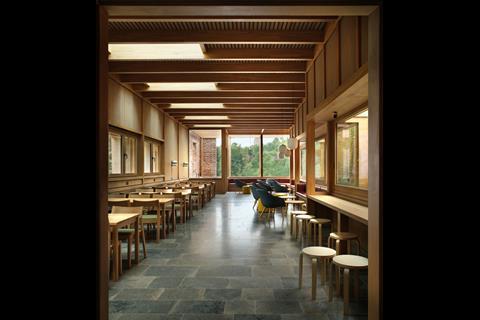

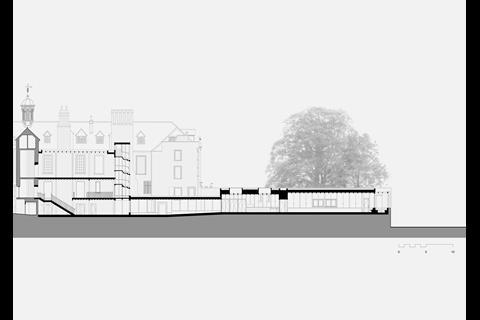

The resulting scheme is a complex interweaving of new circulation and intimate café and servery. A new staircase leads down from the hallway outside the main dining room to basement level, but the resulting new spaces are anything but subterranean in feel.

As the wedge-shaped café widens towards the river, extensive glazing on the north and western elevations brings in light and offers glimpses of the college gardens on the far side of the river.

The entire southern boundary of the café is defined by another existing retained garden wall – in this case, that of Clare’s own Master’s Garden. A new window has also been created here, made using salvaged stone window surrounds from the demolished early 20th-century office that previously sat on the site.

Purbeck Grub stone flooring is used throughout most of this lower level, with precast concrete in place of the college’s original Ketton stone for architectural elements such as openings and lintels. These beautifully crafted interventions on the ground and basement levels flow relatively seamlessly from the original building.

However, a new glazed corridor on the first floor feels rather less well integrated with the rest of Old Court. Intended to provide disabled access to the Senior Combination Room (fellows’ common room) this is a beautiful space, but surely deserved a more clearly defined purpose.

The sense of the brief having not been quite fully resolved is further reinforced by the emergency escape stair, which serves only the attic storey of the building. It is an exquisitely detailed wooden staircase with beautiful views out, but appears destined to be virtually never used.

These are minor quibbles, but they slightly undercut Witherford’s assertion that the practice has successfully amalgamated the disparate elements of the brief into a fully coherent whole. Arguably more significant is the now much improved accessibility to a series of key spaces within Old Court.

The decision to occupy this leftover space has also informed the choice of materials. While the elevations of Old Court that face the quadrangle are faced in stone ashlar, the “rear” northern elevation is built from brick. Witherford Watson Mann’s building continues this language, but with the addition of a wooden structural frame, with brick infill panels.

Sadly for the members of Clare College, the main beneficiaries of this view are visitors to Trinity Hall, as the new interventions are almost invisible from within Clare itself.

Site access and preparation

It is striking that Witherford seems almost as keen to talk about the design and building processes as the finished project itself. It is a refreshing reminder that being an architect can still involve taking a profound interest in the art of construction, and the people whose job it is to do the actual making.

Construction was complicated by issues around access, the listed context and the impact of covid. With the college’s front entrance on Trinity Lane not suitable for construction work, the only option was to access the site from the other side of the river.

Clare Bridge, built in 1639-40 by Thomas Grumbold, has historically formed part of a publicly accessible route through the college, and is the oldest bridge in the city. However, it was deemed not suitable for construction traffic.

The decision was therefore made to install a temporary bridge from the Fellows’ Garden on the west bank of the Cam, across to the Master’s Garden. “We also had to make the site compound in the Fellows’ Garden, which was very emotionally challenging for the college,” explains Witherford.

Preparation work on the north wall took a year, partly because some 1960s additions were embedded into the 17th-century brickwork, and this took time to remove. “They had dug out part of the wall and cast a concrete roof directly into it,” he says. “So, there was a lot of work in breaking it all out, especially as it’s a massively constricted site.”

Freeland Rees Roberts contributed to the design in the initial stages as conservation architects, and extensive research was undertaken by Roland Harris, the historic building adviser.

“Slowly unpeeling that wall, we didn’t actually know what we were going to find underneath it,” says Witherford. “There was a whole kind of slow excavation of what was there. We went about a metre and a half down deeper into the ground. We didn’t know what the brickwork would be like there or whether we’d be encountering foundations.”

The laborious work involved constant minor revisions to the detailed designs. “There was a year of just slowly removing and revealing and remeasuring and just adjusting what we were proposing in small, detailed ways to make sure you could fit this thing in.”

Construction

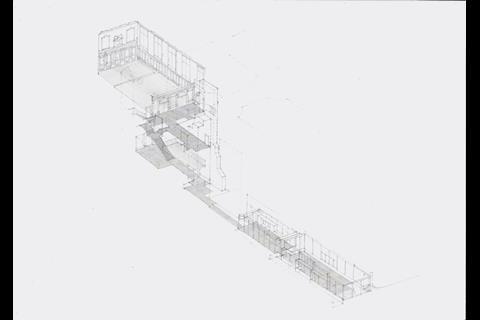

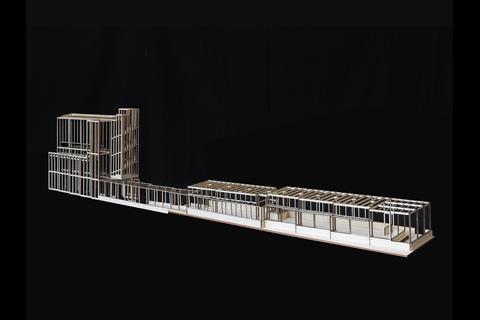

“And then into that narrow gap we put this timber structure,” Witherford explains. He points out how the new structure responds to every detail of the historic building, from window positions to chimneys which widen as they come down. “And the design is completely developed to fit into that set of incidents and spaces and rhythms. All of those incidents set the rhythm of the timber structure.

“I think actually getting things into the site was another factor in how we approached the materiality of the project,” says Witherford. “Everything had to come in over that bridge and be lifted off lorries by crane. And so that really impacted the programme and the cost of the build.”

The decision to use structural timber for the new extension was also based on a desire to achieve very low embodied carbon. “It’s a laminated oak structure,” says Witherford. “Three storeys, and all traditional joints – there’s no metal fixings in there, just screws and glued rods and dovetail joints.

“And this structure is very precise. It’s all pre-drilled and pre-machined by Constructional Timber in Yorkshire. So, it just literally goes together like steel.

“And, meanwhile, you’ve got this wobbly historic building, which you don’t fully know the dimensions of, which is bowing vertically and horizontally. The brickwork is very slightly, gently rolling. And you’re trying to set lines and details to work with that.”

Witherford explains how the frame’s assembly was overseen by a small family subcontractor, working for Constructional Timber. “They were a ma, pa and lad from Yorkshire, and they were amazing. And they erected the whole structure.

“The mum organised everything – she had all the drawings and all the tools ready for every bit. She knew every bit of the sequence, and then the son and the father put it together. They were just this incredible team.

“On site, it was quite quiet to build, which was good. It was fast. It was clean. And, actually, so was the language – when the mum was on site, the whole atmosphere of the site improved significantly.

“So, it took 20 weeks to put up the framework. It was partly slowed down because we were going through an exam period. Because of covid, people at that time could still do their exams in their rooms, so we had to have no working times on site.”

Covid also had other more direct impacts on the programme. “At the time, it was hard to get certain materials, as a lot of manufacturing had stopped, but construction sites had not.

“And, because of Brexit and the pandemic, a lot of eastern European labourers had gone back home, and so there was a labour shortage too. So, there were all kinds of things delaying us.”

A team effort

But client and architect regard the finished scheme as a success and worth the travails they had to deal with. Deborah Hoy, estates director for Clare College, believes the project helps to ensure that Old Court “remains the beating heart of college”.

She adds: “Witherford Watson Mann have taken a warren of underutilised spaces and provided an impressive social experience for all college members to enjoy. The reorganisation… means Clare’s public spaces are fully accessible to all for the first time.”

Witherford attributes the overall success of the project to the client, design team and contractor all pulling together to address the complexities of the site, and the challenges of covid.

“We worked really closely together to share those burdens. You know, as an architect or client, if you just want to make it all the contractor’s issue, that’s fine. But you don’t end up with a building like this. You will never, ever get people to go the extra mile on the craft, and show that patience.

“You know, it’s a commercial building project. And there’s a contract, and a timeframe and the college need their building,” says Witherford. “But, outside of that, there’s also a decision to be made about whether you just cajole, or whether you work things out together.”

He is also full of praise for the civil and structural engineers, describing Smith & Wallwork as “pivotal” to the project. “We wouldn’t have ended up with this building without them, because their appetite and ambition was huge.

“Freya Williams was the project engineer. Normally the contractor has to detail the final connections. But this was Freya’s first big job and, because of lockdown, there was a little more time, and she did 300 connection drawings.

“They’re all individual. And that’s amazing.”

For Witherford, the blending of architecture and structure – a recurring theme for the practice – underpins the success of River Wing.

“We always express structure quite a lot. But I think this is the closest we have ever come to the structure being the architecture. They’re almost one thing, so we were working with Smith & Wallwork on the same three-dimensional models.

“Looking at all of those connections, it’s really three-dimensionally resolved. Which is important, because what you draw and what goes into that CNC machine is what you get.

“The frame is quite intolerant, like steel. Even though it’s timber and you think you could hack it around, it isn’t like that. It’s very precise.”

Witherford Watson Mann has made a name for itself with a series of profoundly sympathetic interventions in historic contexts. At Clare College a challenging site has brought out a richly textured response that brings new life, coherence and relevance to the historic buildings.

And the way in which this project has been delivered by client, architect and contractor only underlines the importance of collaboration in delivering beautifully detailed and satisfyingly finished buildings.

Project details

Site area 1,060m2

Gross internal area 1,742m2

Project value £25.5m for this phase including the river room café, temporary kitchen and temporary bridge/crane, works to existing kitchens and fees. Part of a £42m transformation project delivered in phases.

Project schedule May 2014 to June 2023

Client Clare College

Architects Witherford Watson Mann Architects

Design team Stephen Witherford, Chris Watson, William Mann, William Burgess, Nadine Schuetz, Anna Tenow, Lucy Paton, Freddie Phillipson, Andrew Lane, Vassia Chatzikonstantinou, Antonia Alexandru, Saya Hakamata, Chris Raven, Benny Chung

Project architects William Burgess, Nadine Schuetz, Anna Tenow, Lucy Paton, Freddie Phillipson

Historic buildings advisor Dr Roland Harris

Conservation architect Freeland Rees Roberts

Building contractor Barnes Construction Ltd

Structural engineer Smith & Wallwork

Services engineer Max Fordham

Civil engineer Smith & Wallwork

Quantity surveyor Henry Riley

Project management Henry Riley

Landscape architects Liz Lake Associates

Fire consultants The Fire Surgery

Planning consultant Turley

Oak glulam frame Constructional Timber

Purbeck stone floor Stonebuild

Oak staircase Lowe & Simpson

Pre-cast concrete Cambridge Architectural Precast

Brickwork Anglian Brickwork

No comments yet