Caroline Voet reviews an expanded edition of the 1986 book by Enric Miralles with Alison and Peter Smithson, about their Upper Lawn Solar Pavilion

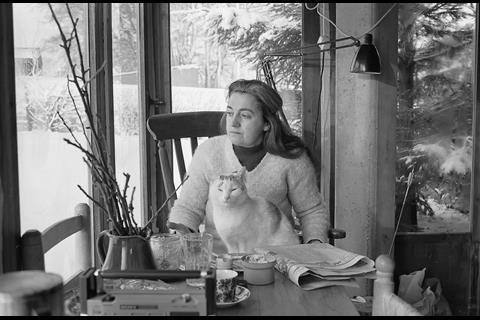

This book revisits the poetic diary, edited in 1986 with Eric Miralles, of the Smithson’s Upper Lawn Solar Pavilion, one of the most intriguing primary houses ever (re-)made. The book invites the reader into all the layers that formed the house, from the environmental concerns and experimentation, to the history and topography of the place, to patterns of family use and appropriation. The peculiar intensity of the book as part of the project grows from the fact that all of these are blended together by Alison Smithson’s diary fragments and both their photography, offering the reader to become part of the evolving nature, life and construction works at the pavilion.

Everything starts with close observation from material traces and events, from the seasonal garden harvesting and jam making to the found and reorganized cottage stones, to the children’s games or the new metal sheeting coming in. The book is a testimony to the Smithson’s venture on creating the absolute essential and elementary dwelling, observing their own performative role in the shaping of the project.

Central to their approach is the superposition of ethics with aesthetics. With their inquisitive and explorative open attitude towards designing and making places, every act of making is entangled with layers of meaning that feed the ontology of a shape, whether it is an object, an exhibition or a building. The pavilion in this is an embryo experiment of their later Conglomerate Ordering concepts or a search for a contemporary vernacular.

We can only hope that publications like these are taken from the shelve, and brought back into the domain of architectural culture to inspire and deepen the debate. With the need for a rethinking of the architectural profession, the concept of As Found, launched by the Smithson in the 1960s, is more timely then ever.

Only in September 2023, the As Found conference, organized in Belgium by The Flanders Architecture Institute and the University of Hasselt, brought together an international and diverse group of scholars and practicing architects who had one thing in common: to connect the themes of sustainability, preservation and adaptive reuse with architectural culture and creativity. Papers such as ‘Restoration as Curatorial Practice’ (Florina Pop), ‘A New Generation of Architects-Repairers’ (Luc Baboulet Luc and Paul Landauer), ‘Rebuilding Memory’ (Amara Goodwin) or ‘Naughty Heritage’ (Alessandro Scarnato) are rooted in the original As Found ideas.

The Upper Lawn Solar Pavilion and its publication are the layered experiment that nurtured the Smithsons thinking in action, from the discovery of the site in 1945 to the acquisition of the Upper Lawn cottage in 1959, and then from the appropriation, demolition and (re-) construction works and habitation until 1981. In the book, the Smithsons introduce the Solar Pavilion’s original intentions as being almost technical and environmental. i

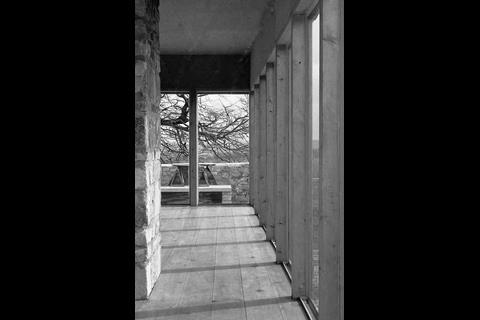

Their aims were ‘to test certain products which were not yet permitted by the Authorities’ in the London area, such as pitch fibre drainpipes and Visqueen sheet DPC. The pavilion also provided the opportunity to ‘try on ourselves certain applications and assemblies of materials’, including high-purity aluminium sheeting or sliding folding doors, and ‘to find out what it is like to live in a house in England all the year round which presents glass walls to entire south, east, and west, but a solid wall to most of the north face’ in relation to solar heat and heat loss.

In the retrospective introduction of 1985, Peter Smithson places the project between the poetics of the Barcelona Pavilion and the practical of Gropius’s Berlin housing: ‘Upper Lawn was a device for trying things out on oneself. It was here we explored those signals for change which we later would come to recognise as being the necessary work of the fourth generation of the Modern Movement.’ But foremost, he admits to finding ways to deal with new conditions of noise, intrusion and solitude, comparing it to Thoreau’s cabin: ‘Upper Lawn was placed in an eighteenth-century English landscape with the conscious intention of enjoying its pleasures, its history, of submitting to its seasons, admitting to the melancholy that seasons and quietness entrain.’

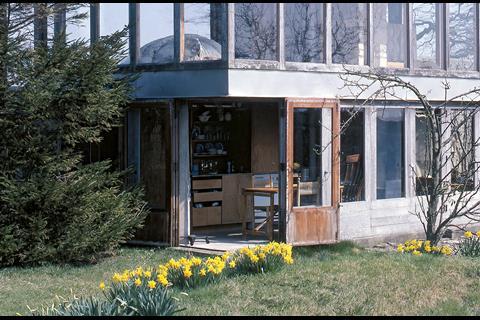

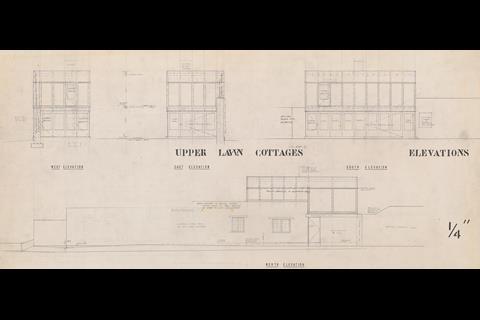

The Smithsons seriously altered the condition of the original cottage in order to intensify the sought-after As Found condition. The pitched roof and most of the walls are demolished, only a central chimney remains. The new house is ‘displaced’, making the old into a ruinous outdoor garden room with the most beautiful window-with-bench to gaze from over the landscape. The new construction of thin wooden frames with glass and metal sheeting is anchored on top of the old wall, and cantilevered over a thin concrete U-shape with two beams placed in a 45° angle.

Its current owners lovingly enjoy the architectonic elementary environment and the intensely intertwined connections with the surrounding garden and landscape, wanting to change nothing. The recent restauration by Sergison Bates aimed for the same philosophy, carefully taking its shape through a slow wandering into all the conceptual, spatial and technical levels of the pavilion.

Solar Pavilion symbolises a specific attitude of care towards society, as an act of cultural resistance and imagination. It is an absolute treat to have this book, now with a new insightful introductory essay by Paul Clarke, made available again.

Postscript

Upper Lawn, Solar Pavilion Alison & Peter Smithson, by Alison and Peter Smithson and Enric Miralles, is published by Mack Books.

Caroline Voet is Associate Professor of Design, History and Theory at the Faculty of Architecture, KU Leuven and leads the practice VOET architectuur in Antwerp, Belgium. Her book Dom Hans van der Laan. A House for the Mind received the DAM Architectural Book of the Year Award 2018. She was co-editor of the book Autonomous Architecture in Flanders (2016) and of The Hybrid Practitioner; Building, Teaching, researching Architecture (2022).

No comments yet