In Form Follows Love, Anna Heringer reimagines architecture as an act of empathy and participation. Sumedha Kelegama explores how the book challenges dominant ideas of design, authorship and durability

In today’s architectural world, overwhelmed by publications that privilege designer subjectivity and conceptualise buildings as autonomous aesthetic objects, Anna Heringer’s book Form Follows Love: Building by Intuition – from Bangladesh to Europe and beyond emerges as a delightful and inspirational rupture. This book is a testament to a different approach to architecture that privileges human relationships, celebrates local materials and knowledge, and embraces vulnerability in the creative process. The book’s imagery foregrounds this message — photographs depict buildings animated by everyday life, where human presence and social interaction take centre stage, and the architecture gently recedes into the background.

The text operates simultaneously as a personal narrative and a theoretical proposition, revealing with remarkable transparency the philosophical underpinnings that animate her architectural practice. The monograph is a thoughtful exploration of architecture’s potential to foster positive social change, emphasising the generative power inherent in the building process and the socio-ecological significance of material choices.

Formative influences and embodied knowledge

Heringer’s architectural sensibilities emerge from her childhood and a formative domestic environment where ordinary objects embodied an intrinsic aesthetic value. She describes this influence directly: “art wasn’t displayed on the walls of our home. But in our daily lives, my father designed things that were necessary in ways that made them beautiful”. This experiential encounter with everyday artefacts recontextualises aesthetics not as superimposed ornamentation but as an inherent quality of necessary objects — a conceptual framework that would later inform her critical engagement with architectural production.

Complementing this sensibility, she traces the embodied knowledge conveyed by her mother. “I learned the importance of the body from her, how to access my intuition,” she observes, establishing the emotional intelligence that would later inform her design approach. These approaches become synthesised in Heringer’s practice, wherein the rational and intuitive coalesce into a methodology that values both material efficacy and affective resonance. The playful and metaphorical idea that one must sometimes “run a red light — take a calculated risk” inherited from her father, manifests as a series of mindful, intuitive and calculated transgressions against the prevailing standards and norms in architecture.

During a voluntary service year with the NGO Dipshikha in rural Bangladesh, Heringer recalls how “my senses opened, my mind calmed, and I was bathed in an ocean of the lushest green I had ever seen,” describing a landscape so vibrant it felt like she was “visually drowning in these paddy fields.” She speaks of the “beautiful houses of mud” built by many hands, their modest scale and material intimacy leaving a lasting impression — an experience that made her feel “at home in that country that embraced me so quickly and with so much heartfelt kindness”.

Furthermore, Heringer’s observation of everyday objects in Rudrapur reveals a profound recognition of the aesthetic intelligence embedded within vernacular practices. She notes that “this inherent and unusual beauty could be found in almost all objects I encountered in my everyday life in Rudrapur… in the saris of the women… in every handmade spoon, on the kitchen knife… every basket, every fishing tool, every terracotta pot”.

This appreciation of the Global South’s material epistemologies — where objects transcend mere utility to become repositories of cultural knowledge through their elaborate craftsmanship — shapes her architectural approach. She articulates, “this is what I try to do with my architecture: value local potential, available materials, and existing knowledge”. This conceptual foundation threads through the book, shaping each architectural intervention.

Embracing irregularity

Heringer’s embrace of an “irregular rhythm” in her built works marks a distinct alternative that privileges organic variations over rational, mechanical repetitions. Her assertion that “even heartbeats are not always the same — they skip a beat when we fall in love. It feels unnatural to make everything so rational. It’s our emotions that bring rhythm” employs a corporeal metaphor to reconfigure architectural articulation. This approach manifests throughout her built works as a vernacular sensibility where aesthetic qualities emerge through intuitive material engagement rather than predetermined geometric systems, positioning architectural rhythm as fundamentally affective rather than mathematical.

Participatory methodologies

Heringer boldly challenges architectural orthodoxy by privileging process over product. She notes that “architects are so often trained to focus completely on designing the final product… designing the process is not enough of a topic in our education. The process is just as important as the outcome”. Therefore, the participatory methodologies embedded within Heringer’s architectural approach invite particular reflection.

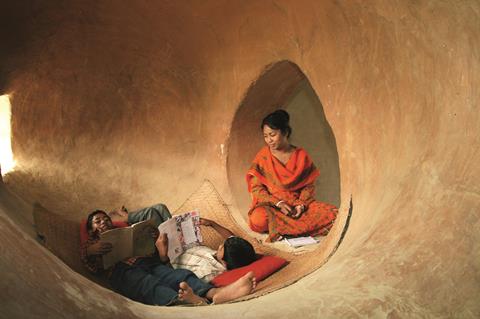

At the METI School, she involved “the future users of the building in the construction process,” deliberately including children under the care of their teachers. While this approach “brought a lot of chaos onto the site,” she notes, “it was completely worth it!”. It also catalysed a broader community engagement by subsequently drawing in parental participation. This methodological intervention facilitated an organic process wherein “the children could naturally take ownership of the school”, repositioning the building as communally constituted rather than professionally imposed.

Furthermore, Heringer’s intervention extended to the social recognition of construction knowledge when “the workers previously considered day labourers were conferred a diploma in earth and bamboo construction” at the METI School’s opening ceremony. This formal acknowledgement, wove the builders back into the tapestry of architectural authorship, demonstrating a beautiful (re)configuration of architectural agency.

Through these approaches, Heringer experiments with alternative frameworks for architectural production in which design emerges through collaborative processes rather than a singular authorial vision. As she poignantly remarks, “It’s never just about the building. It’s much more about the social structures you can create as it is in becoming”.

Decolonising materials and aesthetics

Through her work in Ghana, Heringer reveals how building materials tell stories of power, history, and cultural value. In her current project at the Don Bosco Earth Campus in Tatale, Heringer observes the surrounding local architecture: “beautiful vernacular structures: playful compositions of square and round houses, in different proportions and scales, grouped around a courtyard. And almost all of them are built in mud”. Yet, she pointedly notes that “only the church, the mosque, and the schools are in concrete”, highlighting how institutional power perpetuates colonial material hierarchies.

She observes, “those who come to a place with money, power and academic knowledge often dismiss local potentials and build in concrete or brick, as if existing traditions aren’t good enough”. This material hierarchy functions as a spatial manifestation of knowledge suppression, whereby imported construction technologies supersede indigenous building practices — not due to technical superiority, but through their associations with institutional authority. She traces this suppression from its colonial origins to the present, arguing that “what started a colonialism continued with development cooperation” and asserting that “to decolonise aesthetics and ideals is probably the most difficult task of all”.

Durability

A particularly significant aspect of Heringer’s work is her critique of durability as an absolute architectural value. She recounts her encounter with Bangladeshi villagers’ perspective on decay as “one of the biggest learning experiences in [her] career”. While she initially viewed decay as “an unacceptable disaster”, the local craftspeople interpreted material degradation as an inherent cyclical process that facilitated economic sustainability as “they were happy to have the opportunity to work again, bringing in money [to support] their families”.

This example illuminates alternative frameworks within architecture, wherein regenerative cycles of maintenance constitute both cultural practice and economic sustenance. Her subsequent proposition that “the durability of knowledge is more important than the durability of materials” and call “to design decomposable buildings, and to have a ‘plan of decay’ for every structure” represents a profound reconfiguration of architectural temporality that challenges the discipline’s fetishisation of permanence.

Affective Dimensions of Architecture

Heringer’s work with traumatised populations in refugee contexts reveals architecture’s potential as a therapeutic intervention beyond conventional spatial production, particularly through her Rohingya Refugee Camps initiative in the south of Bangladesh, which reconceptualises building practices as a form of emotional mediation. She observes that “the most important part for them was coming together. The project provided the possibility to speak to one another about the traumas they experienced and thus support each other”.

A workshop she conducted revealed the healing power inherent in working with mud. She explains that “there are different techniques which can trigger different emotions. Those who have too much energy and feel a lot of anger can let off steam by compacting the earth with ramming, releasing aggressive impulses. More gentle emotions are released during plastering work, when you almost caress the walls in order to make beautiful surfaces and add ornamentation”.

This affective dimension extends to her work at the Anandaloy Centre for Disabilities in Rudrapur, also in Bangladesh, demonstrating architecture’s capacity to “shine a light on people and topics that are otherwise overlooked”. The centre’s phenomenological qualities are expressed through its “walls with rounded corners made out of mud and straw, which gives them a tactile quality.” Heringer describes her embodied experience of the space, noting, “when I am walking through the building, I always feel as if I were gliding through it, and body is in dynamic dialogue with the winding shapes, almost like a dance”. This choreographic conception of spatial experience privileges haptic engagement over mere visual appeal, challenging architecture’s privileging of visual aesthetics rather than how they feel to inhabit.

Heringer’s ‘Claystorming’ methodology further extends this embodied approach into architectural pedagogy. Her assertion that “intuition can be trained just as well as analysis and argumentation” constitutes a significant intervention within architectural education’s rationalist paradigms. Against the accelerating digitalisation of architectural representation wherein even the making of a simple model is being replaced by 3D printing, Heringer’s tactile methodology reintegrates corporeal knowledge into design processes. This approach reveals her commitment to architecture as a fundamentally embodied practice rather than an abstracted representation or “pursuing a specific form or style!”.

Gendered critiques of architectural practice

Central to Heringer’s work is a feminist critique that interrogates the masculinised values embedded within architectural practice. Her assertion that “the constant striving for height, size, efficiency, control, and rationalisation, but also the fascination for the novelty and the excessive use of technology – all typically male characteristics – must be brought into a healthy balance with intuition, empathy, care, and compassion for fellow human beings and nature” directly challenges the masculinised ethos underpinning dominant architectural paradigms.

She further critiques the methodological approaches, wherein “emphasis of results over process” is identified as a problematic manifestation of masculinised architectural values. In this light, Heringer’s work establishes gender as a fundamental lens through which architectural priorities must be examined, revealing how traditionally feminine values of intuition, process, and interdependence have been systematically marginalised within the discipline.

Conclusions

Something quite striking, yet extremely refreshing and unique when reading this book, is Heringer’s willingness to share her vulnerabilities and uncertainties. She openly discusses failing architectural exams, losing herself in superficial parameters, acknowledges the artificiality of her early design processes when it was formalistic with an inserted social value, and even questions her role as “a white woman… build[ing] in Africa or Asia, considering the history of colonisation”.

This honesty is both disarming and powerful in a field often characterised by unwavering confidence and self-promotion. The book was originally structured as a series of questions and answers — questions posed by Dominique Gauzin-Müller, to which Heringer responds with thoughtful and expansive reflections. Given the richness of the text, one can presume that Gauzin-Müller’s questions were remarkably well crafted, eliciting the openness and depth evident in Heringer’s responses.

Form Follows Love, constitutes not merely documentation of built works but a critical intervention in architectural discourse, proposing alternative methodological, material, and ethical frameworks for the contemporary architectural landscape. For students, practitioners, and all those engaged with the built environment, this book offers a timely and critical reminder that architecture, at its most meaningful, is not an act of imposition but a practice of cultivating relationships — with materials, with place, with communities, and, ultimately, with the self.

Postscript

Form Follows Love: Building by Intuition – from Bangladesh to Europe and beyond by Anna Heringer / Dominique Gauzin-Müller is published by Birkhauser.

Sumedha Kelegama is a Sri Lankan architect. He has worked on projects across South and Southeast Asia. His work spans architectural practice, teaching, writing and documentary filmmaking.

No comments yet