With the V&A exhibition on Anna Heringer’s earth-and-bamboo Anandaloy Centre ending this coming weekend, Mary Richardson explores the celebrated architect’s philosophy of sustainable design, her battle to bring rammed earth to Europe, and what designers in the Global North can learn from traditional techniques in the South

Celebrated German architect Anna Heringer blends a deeply grounded fascination with earth, and with the future of the Earth, with a quasi-spiritual philosophy. The resulting buildings can be exceptional, and her deep-green philosophy of materials is absolutely of the moment. Few have made clay look so good or seem so vital.

Heringer made her name with a series of innovative earth and bamboo builds in Bangladesh which, as well as having great charm, build upon local sustainable vernacular techniques and materials. Having expanded her repertoire around the world, she is now beginning to build in Europe, something that is presenting a whole new series of challenges.

Heringer grew up in Laufen, a Bavarian town on the border with Austria. Her father was a landscape architect and committed environmentalist, who instilled in her a passion for ecology, while her mother was a kinesiologist who taught her to value the physical and trust her instincts. Both influences can be seen very clearly in her practice today. Theirs was an ethical household run on environmental principles, with no unnecessary consumer goods and homemade clothes instead of the latest fashions.

Another formative influence was the Scouts, where she learned to build using bamboo canes lashed together with rope. This wholesome childhood, against which Heringer appears never to have rebelled, has fostered in her an evangelical green design philosophy that some might call a little unworldly, hippyish and short on pragmatism. But then, all new ideas are unrealistic until they aren’t, aren’t they?

As a Scout, Heringer was more ambitious in her bamboo construction than those of us who, in the same situation, were satisfied with artlessly knotting together three canes to make a tripod. She lashed together a six-metre tower and an elegant, hyperbolic gate for her Scout camp. When she later travelled to Bangladesh to volunteer for an NGO before university and encountered local buildings made with lashed bamboo, it must have felt like kismet.

Bangladesh

The METI Handmade School, her final university diploma project and first build, back in northern Bangladesh, refined traditional bamboo and clay techniques and succeeded aesthetically, functionally and sustainably, with many features that would become standard in her portfolio.

She raised the money for the build herself, and built with earth not just because it was a typical local building material, but because she’d become fascinated by the stuff, inspired by Martin Rauch, German master of rammed earth, for whom she had worked as an intern and with whom she would subsequently collaborate.

Rather than consulting the school’s pupils on the design, Heringer relied on her own memories of being a child, and instead got the children involved in the construction of the earth walls. The lower floor of the building is built of rammed earth set on fired bricks to protect the walls from rising damp.

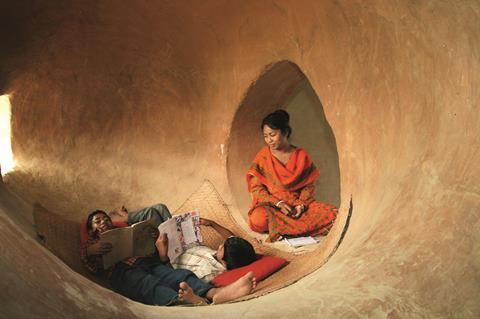

There are three classrooms, as well as small, rounded earth ‘caves’ where children can hide and play. The simple, elegant second floor is made of lashed bamboo. Bright saris hang at the windows and stretch across the ceiling to add shade and colour.

Heringer has said, “The walls of the school were built in 2005, and they have been standing very strongly ever since, even in the face of driving rain in the monsoon season. There are absolutely no chemical additives in the earth walls, only the natural straw… The modernity that many seek comes through design rather than industrial materials.”

At the end of the building’s life, the nylon ropes and steel pins that hold together the bamboo structure will be reusable, and, because no cement has been added, if the roof is then removed, the walls will simply dissolve slowly back into the ground.

In her next build in the village, the Dipshikha Electrical Skill Improvement (DESI) Centre, Heringer sought to design a refinement of a traditional vernacular earth homestead. She wanted to devise a more sustainable model home for upwardly mobile families, who typically abandon earth for tin, concrete or brick as soon as money allows.

The Anandaloy Centre, celebrated in the current exhibition of her work at the V&A, is the culmination of her projects in this part of Bangladesh. Another characterful mud and bamboo construction, on the ground floor it contains a therapy centre for people with disabilities, and above, a workshop for Dipdii Textiles, a fair-trade clothing label founded by Heringer. The V&A show tells the story of the centre through embroideries stitched by the Dipdii Textiles artists.

Bamboo Biennale

Other successful projects to date include guest houses for the Bamboo Biennale in Baoxi, China: wonderful, circular criss-cross bamboo forms resembling giant lampshades or perhaps fishing nets. In Tatale, Ghana, meanwhile, Heringer has designed a school made from the local red soil, with a striking asymmetric, organic form.

The apparently random pattern of openings is carefully designed to create a pleasant indoor climate without the need for artificial cooling and lighting.

She recounts, “I designed the windows to be square and rectangular. But then the women started plastering with their hands, and the shapes became rounded. And it became a completely different façade, a very unique façade. So authentic…

“That’s co-creation, through the process. You have to be in the moment. You have to be very, very sensitive. You have to be very intuitive. You have to constantly make decisions on the spot. It’s a different way [of working], but it’s way more intuitive and way more organic… a much more sensual architecture, also a much more female one.”

Barriers to earth

Bringing these sustainable techniques and materials to Europe has been challenging. Regulations have proved a real barrier. Heringer also detects psychological barriers, believing building designers shy away from using what are perceived as raw and unpolished materials through fear.

She has said, “When we work with natural building materials, there’s always this fear of vulnerability.” For her, the antidote to this is trust: “What I see as my main goal, is to build up this trust while building infrastructure.”

And then there’s the cost of the labour, though on her European projects to date, she’s often made use of volunteers. She feels working with clay is a therapeutic process, for individuals and communities. And, as well as using earth as a building material, she loves to use clay as a design tool, in a process she terms ‘clay storming’, which is instinctual design through swift hand modelling using clay.

Whether she’s working in the Global North or the South, for Heringer, “The most important energy source is human labour. It’s a growing resource. And furthermore, if we don’t use it, we also create a social problem. We need meaningful, purposeful work for everyone.”

Pushing the limits

One of her early built projects in Europe relied on unpaid labour. The congregation at Worms Cathedral, in southwest Germany, tamped earth in a frame to form a minimalist rammed-earth altar. The stark simplicity and humble materiality (very literally earthly) of the altar and matching lectern sit in striking contrast to the surrounding Romanesque cathedral, with its elaborate gold Baroque high altar and sanctuary.

For Heringer, projects such as this are as much about process as results. She sees in the affluent West cultures rich in material goods but poor in social connection. And she looks back nostalgically to a time when communities came together to build (as, say, the Amish still do today), believing the communal process can be great for social cohesion.

“We’re not lacking material things in our parts of the world, but what we lack most is good relationships,” she declares. So, for her, the communal building of the altar was as important as the finished object.

Heringer still lives in Laufen, her home town, with her husband and daughter. She is scrupulous about living frugally in the way she was brought up. She has admitted it is hard to make ends meet through architecture and relies on lecturing and winning the occasional prize to keep afloat.

Heringer has executed a couple of larger buildings in Europe. Her annexe to the RoSana Ayurveda Retreat Centre in Rosenheim, Bavaria, is an organic form built with a timber frame, rammed earth walls, clay plasters and a woven façade of untreated willow.

It’s a pleasant building, notable for its extensive use of natural materials in what is a healing setting. But you get the feeling with this and with her largest European project to date (the St Michael Seminary campus in Traunstein) that regulatory proscriptions have cramped Heringer’s style.

She tells me she’s just completing her “largest structure here in rammed earth.” While it didn’t turn out 100% as she would have liked, she’s proud that they managed to build a large structure in rammed earth, “with lots of participation.”

>> Also read: Form Follows Love: Anna Heringer on building with empathy, intuition and mud

That communal process, she explains, is not just a nice-to-have but a principle she holds dear. “That was very important to me,” she says, “because what I feel we really need to learn from the Global South is that the building process is just as important as the outcome.” For Heringer, architecture is never just about form or function: “You can build up a structure and at the same time you can build up a community.”

Reflecting on the same project in her recent book Form Follows Love, she describes the creative tension involved: “Any project is a balancing act: How far can I push the limits? How far can I stretch innovation before it snaps?”

She points to a major breakthrough in the structural use of earth on her recent project: “In the end at least half of the earthen walls are loadbearing and they don’t have an additional load-bearing column structure made of reinforced concrete.”

For Heringer, each project is part of a larger mission, because, as she puts it, “each new earth building will continue to expand the possibilities for earthen architecture.”

Where to begin

When it comes to encouraging other designers in the Global North to adopt similar materials and methods, she recommends starting small. Earth plaster, she says, can offer a gentle entry point. “You can’t get children or your clients to build a load-bearing wall,” she acknowledges, “but you can find parts of a building that can be constructed using a participatory process.”

Heringer suggests a simple starting point: “Just imagine in every school building, one classroom, one wall done with an earth plaster, designed by kids, parents and teachers together.” As well as involving the community, she says, it would improve comfort by balancing indoor humidity.

“We know contact with earth is something soothing. It’s not just a building material, it’s an element, like fire and water, a very protective and motherly, female element.” She imagines children arriving to find this “motherly element in a classroom. It would be a beautiful thing. We all know how much children like to leave their mark.”

At home, she has her own “mud wall in the back… Pure earth in my home. It really is something that is healing. And it is possible.” She envisions a system where soil from construction sites is sorted for reuse, as plaster, mud bricks, rammed earth and more.

Earth, she adds, has a place in retrofit too. Recalling an internship with Martin Rauch, she describes a “very ugly building from the 70s” that “had no charm, no atmosphere, nothing.” The team added a rammed-earth floor: “The earth was brought in, it looked like an agricultural field, and suddenly the whole space started to live.”

“It was unbelievable how much liveliness and life came into the space… It was not another soulless space anymore.” She hopes to see more such interventions in old buildings.

Values and intuition

Beyond materials, Heringer wants to bring new values to design culture in the Global North. “We should start judging our buildings by how much knowledge is created [in building them], by how few scars are left for future generations, and how regenerative the resources are.”

She warns against robbing future generations of the “ability to build with local resources,” stressing that we can’t predict their needs.

Too often, she says, recent architecture has embodied “male” values, “control, and efficiency, How can we get faster, higher, bigger? How can we explore new materials instead of taking care of the old ones?” Outcomes have been prioritised over processes: “The process is often a matter of control and efficiency and not so much of care.”

For her, what’s needed is a major shift. “There’s so much that’s going to have to change, the systems, the rules… Intuition has to be able to play a part again.”

Heringer believes architecture has lost touch with its instinctive roots. “Our best decisions come from intuition, from gut feeling,” she says. “But we unlearn that in architecture and education. We learn to analyse, to argue. If you’re smart enough, you can argue and find arguments for everything. But it needs to feel right.”

She points to the kinds of places we tend to seek out for holidays, those with atmosphere, charm and apparent authenticity, as evidence of the value of intuitive design. “They were born in a very similar way; out of this intuitive process, out of the making rather than a cut drawing or a grid system inserted top down,” she says. “We need to find a way to access our intuition again. Otherwise, our structures will become more and more inhumane.”

Against perfectionism

She is also critical of the way visual perfection has come to dominate building culture. “Out of perfection[ism], we also use so much more materials than we need; so much more steel because we want to prevent the cracks, not the structural cracks but the optical cracks.” The same goes for coatings and finishes: “We use way more paint and varnish, too, to make things look shiny and perfect, than is good for our planet.”

In prioritising appearances, she argues, we’ve overlooked what really matters. “We invest all this energy on the outside surface and forget to care for what’s inside: what sort of insulation, what kind of foam, what kind of glue.” That new-apartment smell? “Well, what it really smells of is toxicity. But we accept that.”

Instead of chasing surface perfection, she urges designers to focus on replacing harmful materials, and restoring health to buildings from the inside out.

The role of ornament

Heringer’s aesthetic arguably places her within the organic tradition of architects like Gaudí, and perhaps Hundertwasser, whose buildings stem from a deep engagement with nature and craft. At the same time, she belongs alongside Bangladeshi architects such as Marina Tabassum and Kashef Chowdhury, who have reinterpreted vernacular techniques for contemporary practice. Her strong social ethos recalls the spirit of Samuel Mockbee’s Rural Studio, while her commitment to traditional materials and to architecture as a tool for empowerment suggests a clear intellectual debt to Hassan Fathy.

I ask her about the role of ornament, and she reflects, “It’s so good for the soul to make ornament. It comes from something so natural. You put your love, your joy, your time and your care into them. But once you cast the things, then they become very weird.

“Ornament then becomes a superficial thing, some kind of sticker or ‘application’. I think that’s when we started to become detached from ornament because we sort of couldn’t afford the real, playful kind.”

So she believes, in line with William Morris, that it was once ornament became mass produced, rather than handmade and applied in situ, that it lost its power and we fell out of love with it. And she blames the insatiable consumerist need to fill and refill our homes with knick-knacks and decorative objets on an unsatisfied need to be physically involved in the creation of our own living spaces.

It’s an argument I’m not entirely convinced by. Evolutionary psychologist Gad Saad, for instance, attributes our appetite for ‘stuff’ to the desire to signal status, a far cry from unmet creative urges.

Love vs fear

There’s a strong New Age streak in Heringer’s philosophy. The underpinning love-versus-fear dichotomy, for instance, comes straight from the hippy bible A Course in Miracles.

She puts it starkly: “Imagine one day we’re all living in neighbourhoods and houses built using the primary emotion of fear as a decision-making tool. It’s horrible.” For her, fear must be displaced by a single, stronger force: “there’s only one emotion, one thing in the world that is stronger than fear, and that’s love.” When decisions are made from that starting point, she argues, sustainability follows: “And if we start making our decisions out of love for others and for nature, then sustainability happens in a completely natural and effortless way.” Hence the mantra she proposes: “And that’s why my wish is that we exchange this ‘Form follows function’ mantra into ‘Form follows love.’”

Saad also has an interesting take, though on a different point: the origins of moral purity expressed through ethical consumption choices. He traces this impulse back to the physical disgust response that evolved to help us avoid disease, a response, he argues, that has been transferred to moral issues as a way to signal superiority.

What saves Heringer’s work from the whiff of virtue-signalling is the evident joy it conveys. She clearly delights in organic forms, colour and ornament, and in the physical process of working with clay. The name Anandaloy itself means “place of unbridled joy”. And it’s Heringer’s ability to make natural buildings decorative, playful and characterful, as well as sustainable, that makes her work so compelling.

Postscript

The story of the Anandaloy Centre is explored in the exhibition Threading the Needle: Architecture of Care at the V&A Kensington in partnership with RIBA until 3 August, 10am – 5.45pm daily.

No comments yet