Contemporary artists shine a light on the haunting aspects of building design, writes Joe Holyoak

Our familiar images of urban scariness are mostly pre-modern. Think of Count Dracula running up the 199 steps in Whitby, or Burke and Hare’s trade in Edinburgh, or the shadowed baroque streets of Vienna in Carol Reed’s film The Third Man.

Gothic is almost synonymous with menace, and it evokes unsettling pictures of steep unlit staircases, narrow alleys, dark vaults, and vertiginous balconies. The gaunt house overlooking the Bates Motel in Psycho, with its verandah and steep roofs silhouetted against the sky, and its corpse sitting in the cellar, is more Second Empire than Gothic, but it epitomises architectural scariness.

The modernist utopian vision has a dystopian underside

Modernism was supposed to put an end to this. Modernism aimed to remove darkness and mystery, and to replace them with lightness, transparency and openness. It was seen as the physical and environmental correlative of a new modern society which would deliver democratic freedoms and human rights to all people, enabled by transformative technology.

It was utopian of course, but some parts of the programme did arrive successfully. In this country, one might name Ralph Erskine’s Byker development, Walter Segal’s housing schemes in Lewisham, and Accordia in Cambridge.

But all is not sweetness and light. The modernist utopian vision has a dystopian underside, particularly manifested in municipal housing developments built to accommodate poorer tenants. Here, the language of modernism became an expedient means of building repetitively at a large scale, uninformed by much in the way of a liberating enlightenment.

When I see a detective in Line of Duty or Prime Suspect approach a deck access flat, I know something bad is about to happen

The determinism debate, about whether or to what extent an oppressive environment creates or encourages anti-social or criminal behavior, continues. But we have certainly made some new scary places: modernism has added to the lexicon of dread. When I see a detective in Line of Duty or Prime Suspect approach a deck access flat, I know something bad is about to happen.

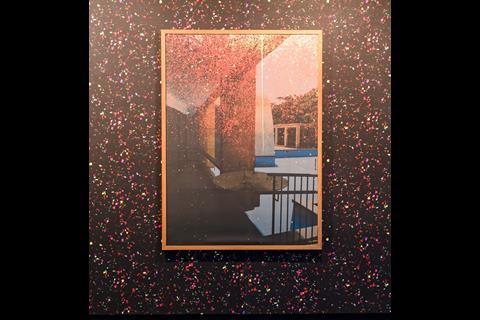

There is currently an exhibition at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham called Horror in the Modernist Block. It is a diverse group exhibition which “explores the troubled histories and legacies of modernist buildings”, and its 20 or so artists do so in film, photography, sculpture, painting and drawing. The show’s content is perhaps not entirely coherent, but it is interesting.

One of the smallest exhibits is easily missed, being placed high over the doorway leading out of the exhibition. Exit Sign by Abbas Zahedi is just that: but the illuminated broad arrow on a green background is flanked by pictograms not of stick figures running, but of stick figures falling – a reference to the catastrophe that was Grenfell Tower (which in its present Christo-like wrapped form is itself an horrific art work).

The exhibition guide cites Brutalism, not entirely fairly I think: the French-derived name unfortunately suggests a connotation with brutality, which is not justified. But the gallery bookshop has an impressive display of books on Brutalism, and on my visit the book Birmingham – the Brutiful Years, which I reviewed here in November, had sold out.

The Birmingham-born artist Richard Hughes, who recalls his youthful skateboarding under John Madin’s Central Library, exhibits Lithobolia Happy Meal – chunks of simulated concrete, which might be fragments of the now-demolished Brutalist library, suspended from the ceiling, and shaped to represent giant Chicken McNuggets.

The horror in the exhibition’s title is perhaps hyperbole. Most of the exhibits represent discomfort, or distress at worst. There are exceptions to this. Ho Tzu Nyen’s video installation of a dilapidated housing block in Singapore shows urban decay (here not an expensive eyeshadow, but repulsive mould and vermin), and evokes the isolation and trauma that can be the experience of living in a high-rise block. Karim Kal’s documentary photographs of public spaces in housing estates at night are also disturbing. The foreground is lit brightly by flash, and beyond is a deep realm of darkness that nobody would wish to walk into alone.

One might conclude that historic environments are not the sole province of urban dread: it exists also in modernist environments of the 20th century. Indeed, perhaps it is independent of any kind of environmental factors, and can be found anywhere. The truth is surely that it lives inside us, generated by the existential fear that we all carry with us, all the time, everywhere.

Postscript

Horror in the Modernist Block is at the Ikon Gallery in Birmingham. The exhibition continues until 1st May 2023

1 Readers' comment