Far from showing signs of sophisticated local government decision-making, Birmingham seems more lost than ever, writes Joe Holyoak

As reported in BD on 1 February, Birmingham’s planning committee reconfirmed its approval of the planning application by Commercial Estates Group to demolish the locally-listed Smallbrook Ringway Centre building, and replace it with a highrise residential development, of build-to-rent flats, of up to 56 storeys. This second hearing of the application was requested of the council by the barrister for the campaign group Save Smallbrook (of which I am a member), who in a legal challenge brought to the council’s attention some irregularities in the previous procedure.

The group had hoped the committee might reverse its earlier narrow decision from September 2023. In fact it repeated it, in an even briefer session. The original vote was 7 to 6: the vote the second time was 7 to 4. Two councillors who voted against the application on the first occasion evidently did not consider it important enough to turn up, and the matter was wrapped up within 20 minutes.

Richard Hatcher, lecturer in the School of Education at Birmingham City University, has since written “Whatever one’s view on the Ringway, the Planning Committee procedure for dealing with a major city centre development is a complete joke. Hours should be set aside for a serious examination of the issues, allowing the full participation of citizens as well as Councillors.” It’s a good point.

Save Smallbrook’s opposition is based on three arguments: for the architectural and urban design distinction of the 1962 Ringway building; against the enormous release of carbon caused by its demolition and redevelopment (a whole-life figure of 187 million kgs of CO2 is CEG’s calculation); and against the derisory number of “affordable” dwellings proposed by the developer as a proportion of the planned total of 1,750 dwellings (4.4%, compared to the city council’s policy target of 35%).

None of these issues was debated in the planning committee meeting. Instead, we heard brief dismissive comments by those voting in favour, and two of the four councillors voting against did not bother to speak at all.

Hatcher cites a new policy document from the city council that was published, with an introduction by the Deputy Leader, Councillor Sharon Thompson, in September 2023. It is called Powered by People: putting the public at the heart of everything we do. It proposes a radical revision of the conventional top-down way in which power is exercised in the city.

Under its four Public Participation Goals it states that the policy “….. commits all of Birmingham City Council to empower the public to shape the places in which they live”. But since a limited public presentation of the policy on 5 September, nothing further has been heard of it.

> Also read: Council confirms demolition of Birmingham’s Ringway Centre after legal challenge

The idea of the retention and conversion of the Ringway building certainly divides opinion. In my view it is not helped by the labelling of the building as Brutalist, which my colleagues in Brutiful Birmingham, partners in Save Smallbrook, regularly do. Architects know that the term derives from the French expression beton brut (raw concrete). But to the lay public the word brutalist suggests something unpleasant and objectionable, and councillors use it to justify their dislike of the building.

I don’t regard the Ringway building as Brutalist anyway. I subscribe to Reyner Banham’s definition that Brutalism is an ethic, not an aesthetic: the ethic of demonstrating what a building is made from and how it is put together, with nothing being concealed. The Ringway building is in fact an elegant, urbane Modernist piece of 1960s architecture.

The Smallbrook Ringway campaign has certainly attracted some notable supporters, who may or may not regard it as brutalist. Jonathan Meades is an admirer, and has said “Birmingham’s appetite for self-destruction is boundless.” Three Stirling Prize winners - Haworth Tompkins, Caruso St John and Niall McLaughlin – signed up last year in support.

In January, Kevin McCloud sent a video from Australia in which he advocated to the planning committee, in his inimitable way, the retention and repurposing of the Ringway Centre: “…..a beautiful long thing, a ribbon of craftsmanship, of 1960s optimism.”

More recently still, and perhaps surprisingly, the Humanise Campaign, a declared opponent of boring, repetitive modernist office buildings, has defended the building, under the title Humanising the Birmingham Ringway Centre. “We thought we’d imagine what a ‘humanised’ vision of the Ringway Centre might look like ….. celebrating the Ringway’s most interesting features, such as the uplights and the intricately detailed frieze.”

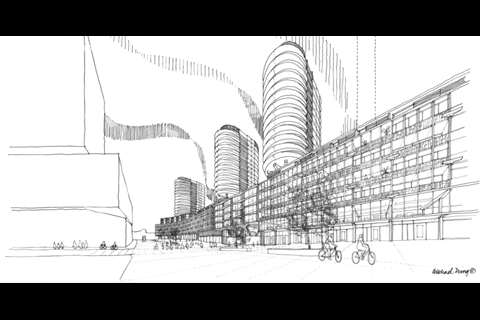

Illustrated by some rather unpleasant CGI photo-montages, the proposed humanising seems to consist mainly of the growing of plants across the building. The Humanise Campaign asks for “a more creative and optimistic solution” instead of Corstorphine and Wright’s colossal yet banal proposed redevelopment. But he seems unaware that this solution is already on the table in the form of Save Smallbrook’s published retrofit counter-scheme, designed by Mike Dring.

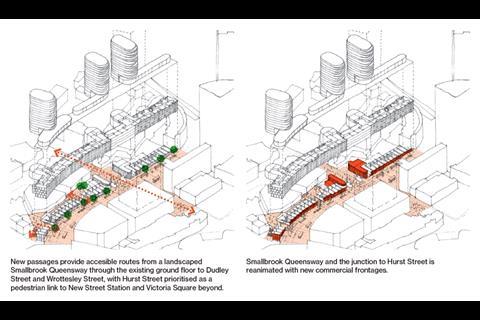

One of the reasons advanced by advocates of the Ringway building’s demolition, which was cited by Tom Hewitt in his recent column in BD about the case, is its claimed lack of permeability, and its acting as an “obstacle” to pedestrian movement between the city centre and Chinatown. A similar accusation was also trotted out to justify the demolition of John Madin’s Birmingham Central Library in 2016. In both cases the accusation is unjustified. But Mike Dring’s counter-scheme includes additional pedestrian routes through the “town wall” Ringway building, increasing permeability while retaining its impressive street-enclosure.

I admire Tom Hewitt’s ingenuity in inserting no fewer than four separate placements for his company BDP into a column ostensibly written on a different subject. But he fails to make a convincing case for the redevelopment of a building that the Birmingham Pevsner guide calls “the best piece of mid C20 urban design in the city”, and a building which is demonstrably capable of a beneficial retrofit.

Hewitt anticipates a future in which difficult decisions in the city are made by “an increasingly sophisticated and informed ….. local government”. I wish this were true, but I see no indication of its appearing.

> Also read: Birmingham’s Ringway Centre decision is the right one for the city

Postscript

Joe Holyoak is an architect and urban designer practising in Birmingham

No comments yet