Diego Calderon and Gianmaria Givanni make the case for how clear, community-led design guidance could enable permitted development to become a tool for coherent neighbourhood growth

Permitted development (PD) rights have become an increasingly important tool in addressing housing needs and enabling urban regeneration. By reducing certain planning regulations, PD facilitates the adaptation and expansion of existing homes, allowing individuals to respond flexibly to changing household needs, while collectively offering broader socioeconomic benefits. However, without an overarching strategy, the long-term impacts of such piecemeal development can be unpredictable and, at worst, harmful to the character and coherence of established neighbourhoods.

The streamlined nature of PD is both its strength and its risk. While statutory guidelines aim for simplicity, they are often too generic to address the nuanced constraints and sensitivities that define specific local contexts. The result can be a gradual erosion of neighbourhood identity, with cumulative changes that undermine the quality and cohesion of the built environment.

Recognising this tension, the Chalcots Estate took a proactive step: commissioning Givanni Associates and DF_DC to develop a set of community-specific design guidelines for the Quickswood sector in Primrose Hill, a hamlet of inner-city low-density family homes built in the late 1960s on land owned by Eton College. These guidelines aim to ensure that PD contributes positively to the estate’s future while protecting its present-day character. Central to this approach is the understanding that while homes may be developed individually, the impacts of those developments are shared by all.

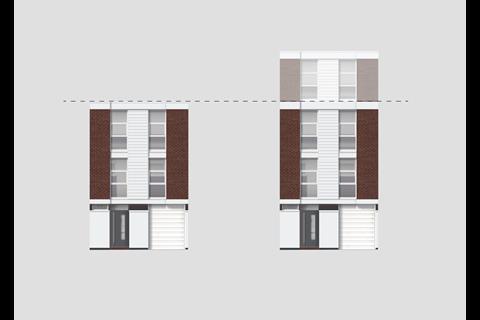

The guidelines are divided into two key areas: the first addresses massing and its effects on neighbours, communal spaces and the streetscape; the second focuses on materials and buildability, supporting consistent, high-quality outcomes through construction. Rather than impose rigid uniformity, the framework encourages variation within a shared language, which preserves both coherence and individuality.

From an architectural standpoint, the guidelines draw on a deep understanding of the estate’s evolution. They reflect the original design intent as well as the organic changes that have occurred over time. For example, unregulated window replacements have been absorbed into a more cohesive architectural vocabulary, using horizontal and vertical bands to weave new interventions into the fabric of the terraces. In this way, the strategy ‘stitches’ the missteps of the past into a more harmonious whole.

Crucially, the guidelines extend beyond aesthetics. For instance, a structural study of the estate’s original precast concrete beams has informed key technical parameters to help homeowners implement changes with confidence and precision. Suggested construction layers and specifications of the salient components of the external envelope offer a practical toolkit for homeowners, architects and contractors, ensuring that extensions built at different times can still align visually and structurally.

Importantly, the design framework is not static. As the estate develops incrementally, the guidelines are designed to evolve, allowing the community to revisit and revise them as the context changes. This built-in flexibility enables a shared vision that remains grounded in lived experience rather than abstract ambition.

Community engagement has been a foundation of the entire process. The guidelines were developed in close consultation with residents, and their adoption was formally voted on. In doing so, the project redefines planning not as something done to communities but with them. The result is a document that is technically robust but also accessible, clear and rooted in collective benefit. The guidelines also assist the estate management body to assess potential applications with the confidence that decisions conform with the benchmark of the guidelines, which are robust and have the overarching agreement of the majority of residents.

Ultimately, this case study illustrates that permitted development is not inherently a threat to neighbourhood quality. On the contrary, with thoughtful design guidance and active community stewardship, PD can support adaptive, inclusive and context-sensitive growth. What is needed is not more restriction but better frameworks: ones that empower homeowners, who are the current custodians of the built fabric, while safeguarding the long-term social and spatial integrity of the places we share.

>> Also read: RIBA calls for urgent review of permitted development rights

>> Also read: Architects need to embrace the reality of permitted development

Postscript

Diego Calderon is co-founder and a director of DF_DC. Gianmaria Givanni is director of Givanni Associates.

No comments yet