Tony McIntyre enjoys a journey through the RIBA’s drawings collection

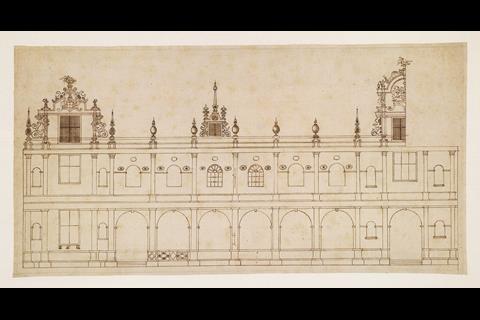

From its foundation in 1834, the RIBA (prior to 1866 simply the IBA), as an institute dedicated to the ‘advancement of civil architecture’, began collecting books but also drawings, with didactic intent. This began with drawings donated by members and were on the whole contemporary works.

The collection of historic drawings was a slower and more piecemeal process. What set the collection on the course to becoming what it is today was the donation by his son Robert of Edwin Lutyens’ drawings – 80,000 in number – in 1951. A decade later the brilliant John Harris was appointed as the collection’s first full time curator, and subsequently acquisition became more proactive.

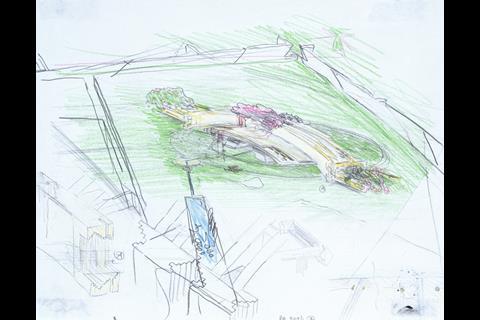

This volume draws on that extensive archive. Apart from its varied selection of drawings, we have an excellent history of the collection by Charles Hind and an incisive essay by Hugh Pearman. In ‘Pure Drawing’, Pearman addresses the question of drawings of architecture as opposed to the buildings to which they may give rise. ‘Architecture does not have to be built to exist’, he insists, also pointing out that drawings often – perhaps more often than not – outlast the buildings they represent.

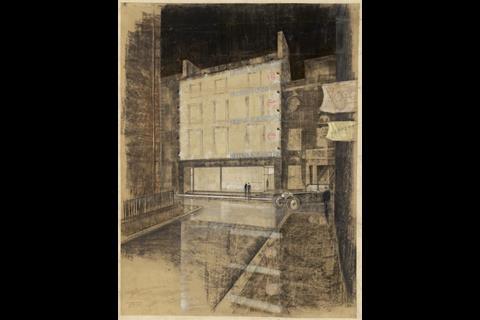

The various Gandy paintings of Soane’s Bank of England are a case in point. These images further illustrate the practice of architects handing responsibility for presentation drawings to outside artists, which became increasingly common over the years and is now almost universal. In terms of design, rather than presentation, the act of drawing is of course a form of thinking, and hence the RIBA’s stated aim to collect drawings that illustrate a project from conception to completion.

This book aims, with its themed chapters from ‘Concept’ to ‘Technical and working drawings’ and ‘Study sketches’, to illustrate that process. (Additional chapters cover ‘Fantasy architecture’ and ‘Born digital drawing’). That is an ambitious aim, and I’m not convinced that the authors pull it off.

To be properly didactic one would have to look at a few single projects, illustrated step by step. One gets little sense of a continuous design process from the projects illustrated here, and the intellectual setup seems forced.

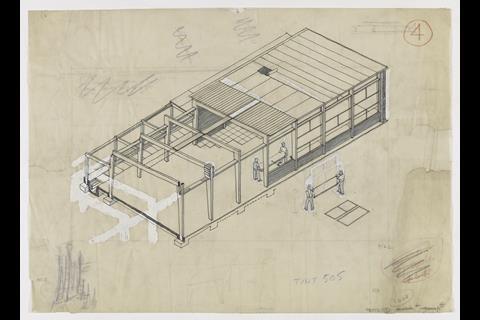

But does that matter? Apart from one or two drawings one feels were added because of the fame of the architect – do we really need Maxwell Fry’s not-very-well-drawn axonometric of a small, dull bathroom? – this is an informative and sometimes amusing collection of work.

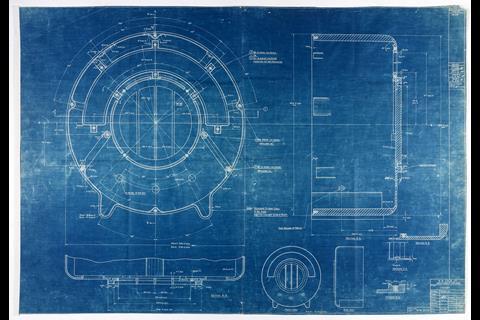

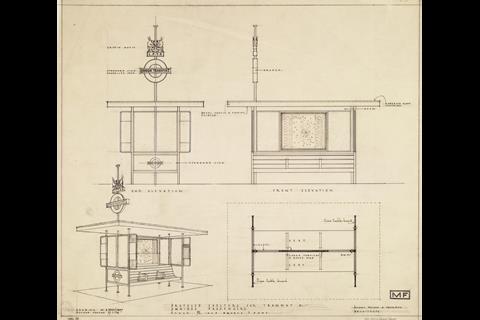

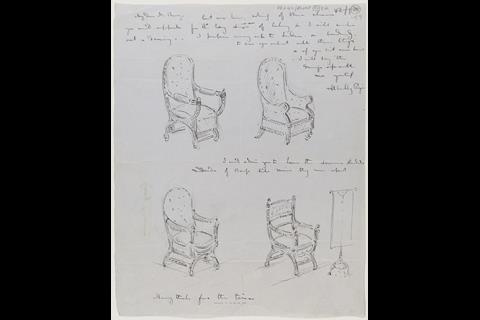

The scale of projects ranges from Pugin’s armchairs for the House of Lords to Richard Meier’s design for the Getty Center of Art. In between are designs and studies of everything from geodesic domes and Bakelite EKCO radios to bus shelters and opera houses. The final chapter, Born digital, makes a striking conclusion to the volume.

Nevertheless, a good book, full of treasures from one of the world’s great collections

The drawings are predominantly of British architects, or rather, of architects working in Britain. Because as well as Inigo Jones, Chambers, Pugin and Foster, we have had a wealth of foreign-born designers working here, from Lubetkin and Coates to Behrens and Goldfinger. Additionally we do get stars like Palladio, Scarpa and Boullée.

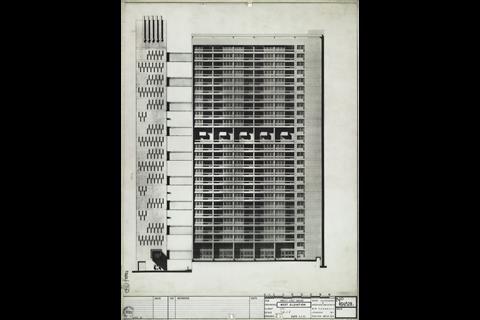

Each drawing has an extended caption, giving social and historical context. These are always informative, and a drawing of Lasdun’s National Theatre appears, with a complete description of Letratone, what it was and how it was applied; which struck me as rather quaint.

The reproductions are adequate but not brilliant. When you get the magnifying glass out to home in on detail, you are disappointed – the detail has been lost. Lines tend to have a blurred halo around them, as if low resolution images have been pushed too far.

There are also several amusing grammatical slips. Confused participles give us, “Although a fantasy, Lutyens was clearly inspired by Venice…”; and it seems that poor Beresford Pite was, “a completely fantastical creation, running along the bottom of the main perspective view…”. (I don’t mean to be cruel, but where were the editors? Further examples of this error are found throughout.)

Nevertheless, a good book, full of treasures from one of the world’s great collections.

Postscript

The Architecture Drawing Book: RIBA Collections, by Charles Hind, Fiona Orsini and Susan Pugh is published by RIBA Publishing.

1 Readers' comment