Giles Heather finds a new book on the London mansion block uplifting, but wonders whether the contemporary typology needs to be better defined

Paris has just re-enacted a citywide ordinance banning buildings more than 37 metres, or twelve storeys in height. In the intervening, shamelessly Anglo-Saxon interregnum, Herzog and de Meuron managed to squeeze a rather odd pyramidal tower through planning. They must have a certain ambivalence about it since it’s very reticent from one perspective and quite unabashed from another.

Regardless, this chunk of Toblerone occasioned the reimposition of the height ban. Quite right too – isn’t the point of Paris, or metropolitan Paris at least, to be impossibly glamourous and palatial – grand and low?

The ever so distinct architectural language of French classicism, first royal, then aristocratic, gestated for centuries, but was turbo charged by Baron Haussmann’s transformation of the city under the Second Empire. The resulting construction boom meant that even the (well-to-do) middle classes were able to rent in style along a breezy boulevard.

This is the Paris that we know and, though a comparatively late arrival typologically, the grand apartment building defines it.

London isn’t, I feel, similarly defined by its approximate analogue, the mansion block, which has accordingly retained just a hint of the foreign and cosmopolitan - even if the architectural language is more extruded domestic than subdivided palatial.

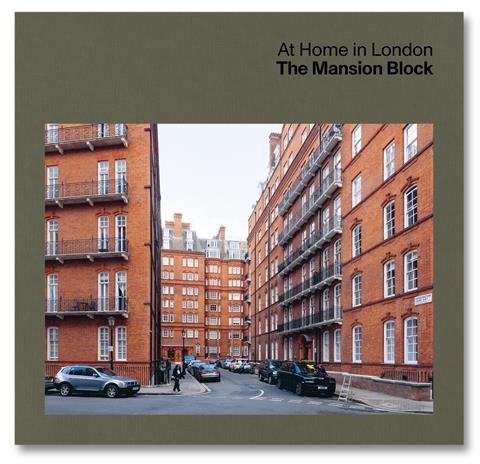

Karin Templin, the author of At Home in London: The Mansion Block, presents a diachronic selection of key exemplars from the 1860s to the present day. Those early developments were all, interestingly, build-to-rent and their construction was precipitated – spoiler alert – by a housing crisis .

It is surely no coincidence that it as the capital is beset by another housing crisis, that the best and brightest are once again ceaselessly labouring to provide high quality and humane speculative development to accommodate the greatest number of people.

This is the spirit in which the book is offered – although perhaps more in hope than expectation – as a plea for civility, variety, density and delight. It’s a shame that this is most often confounded by the political and economic context that determines the type and quality of residential development.

Which is not to say that modernity has a monopoly on the big and brutal. One of the very first mansion blocks, Queen Anne’s Mansions in Victoria, started in 1873, rose to thirteen sheer storeys and had almost no decorative features or tectonic articulation. Unloved, it was demolished in 1973.

For Templin, it’s the modulating features as well as engagement with the street that give the typology its moral worth, with complex and textured facades providing a unitary civic interface with multifarious private realms.

Each example is presented in a standard format, with monochrome plans of ground and typical floors at 1:500 or 1:750 and a selection of images. It’s a handsome book, with a square-ish format giving the visuals plenty of room to breathe, although the aesthetic of the book is perhaps prioritised over its intended use as a primer. It’s sometimes hard to interpret plans that make no distinction between common and private spaces, for example, which makes it hard to use in this practical way.

The periodisation set out in the book is instructive, revealing, perhaps unsurprisingly, greater commonalities between examples grouped between 1852-1903 and 1930-37 than those selected between 2010-22. Of course, society has changed vastly, and so too has policy. What might, in one era, have been regarded as acceptable might be proscribed in another.

The development of core design and requirement for private external amenity, for example, place limits on the utility of the comparative design data presented. On the other hand, it does raise the question of the enduring desirability of buildings one would be prevented from designing today, over what are often functionally compliant but joyless contemporary dwellings.

When one gets to the present day, there is a slight sense of the formal disintegration of the typology, which might just reflect the limitations of the use of the term mansion block or the arbitrary coupling of disparate types of multiple dwelling. Some threads might also have been more clearly presented thematically, for example where the palazzo line of thought can be traced from Henry Ashton’s 13-67 Victoria Street to Amin Taha’s 15 Clerkenwell Close.

Overall, Templin and Mack are to be commended on setting out the case for beautiful and civilised mid-rise urbanism over cookie-cutter towers and jagged, perimeter block-defying development, but a little less neutrality and detachment would aid the cause.

Postscript

At Home in London: The Mansion Block, by Karin Templin is published by Mack

Giles Heather is director of Goldstein Heather Architects

No comments yet