Giles Heather finds an exhibition of Peter Marlow’s English cathedral photographs evokes a medieval sense of longing and hope

There’s something rather indecent about artificial light; it’s prurient and insists on being let into every last nook and corner, making everything obvious and explicit. This particularly applies to the phenomenon of over-lighting spaces, even churches, which, of course, makes perfect sense in a predominantly commercial culture. But commerciality and its moral antecedent, prurient possessiveness, remain on extremely good terms.

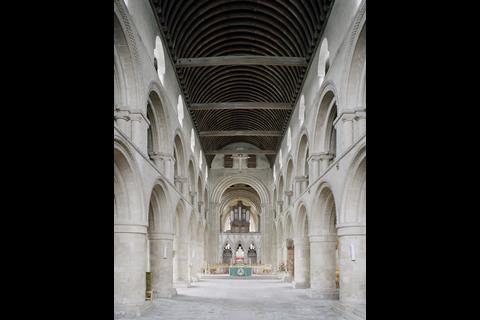

This desire to see everything at once with nothing held back has even had an impact on our medieval cathedrals; prior to the protestant reformation, such spaces would have been relentlessly partitioned, sequenced and controlled. Screens open, screens solid, lofts, walkways, reredoses all expertly martialled the devotional curiosity and desire of the medieval worshipper.

What the medieval Catholic mostly regarded as a sacred hierarchy of spaces, his Calvinist successors radically modified, having reimagined the clerical state – and a sacrificing priesthood made way for ministers of the Word. This, slowly, admittedly as much through neglect as principle, opened up cathedral churches.

The Victorians were perfect contrarians, loving the aesthetics of Gothic but reviling the social and economic conditions that formed it. Even as they restored and saved our medieval patrimony they often removed screens from churches, because of that prurient itch to possess everything, even a vista, at once, an itch that no amount of patristic liturgical and theological ressourcement could overcome.

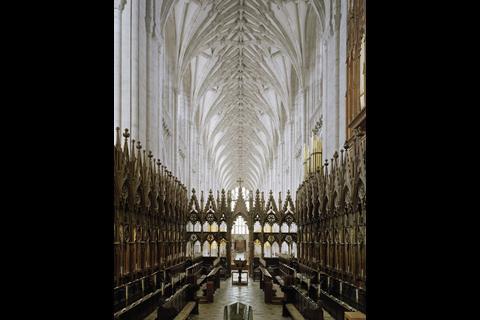

Peter Marlow (1952-2016) spent two years capturing the forty-two Anglican cathedrals from a set position in the morning light, with as much modern clutter out of the way as possible and with all the lights turned off. I have picked up his book of these photographs before and marvelled at the limpidity of the images.

Not having crude felt banners, kiosks and welcome-stations certainly helps and sometimes he has even persuaded vergers to wheel away the nave altar podiums that destroy the proportions of surviving screens. But it really is the light that makes the difference, an effect that was heightened by the crystalline, hoar frost cold morning light streaming into the south nave aisle of Saint Paul’s Cathedral where the forty-two images are currently being exhibited on the day that I visited.

I see everything, every acanthus leaf, even the lines formed by tesserae, but the quality is demure and perfectly balanced. Everything relates to everything else to the appropriate degree, no relationship is distorted by artificial light; the vistas are unmanipulated as I walk around in wonder thinking to myself how great an architect Wren was.

Of course, Marlow’s vistas are manipulated, corrected for perspective, blemishes, with even the odd artificial light having been removed. I gravitate towards the images that evoke this near forgotten medieval sense of longing and hope, of light bursting through east windows, bathing withheld spaces, behind closed screens, in a perfect whiteness: St. Alban’s, the utter stillness of Southwell Minster, Norwich and Gloucester.

His fixed point, mostly facing east but occasionally pointing west also does an excellent job of conveying differential scale. The intimate delicacy of one of my favourites, Exeter, is perfectly captured. Placing the images side by side in a long line tempts my perhaps overly male need to draw comparisons: Invariably, the smaller parish churches more recently elevated to cathedral status slightly pale beside the ship like proportions of a York or Lincoln.

Marlow finished this set in 2011 and they were first exhibited in Coventry in 2016, just a few weeks after he died. He had spent most of his career as a social and political photojournalist. These radiant images place themselves in a long line of documentation, creeping towards eternity.

Postscript

Peter Marlow’s The English Cathedral is at St Paul’s Cathedral until 26th January 2023. This exhibition is included with Cathedral admission and can be found in the Cathedral’s South Nave aisle.

1 Readers' comment