Giles Heather finds that this latest volume of collected works sheds fresh light on the practice’s profound interest in history and alternative modernisms

I make two confessions at the outset of this review – firstly, I haven’t read Volume 1 of Collected Works 1990-2005, despite having bought it for my own practice. Which points to my second – that, even though I am an unabashed Caruso St John fanboy, I can’t shake the feeling that monographs are not really meant for reading, but display – as signifiers of taste and a shamefully bourgeois desire to possess.

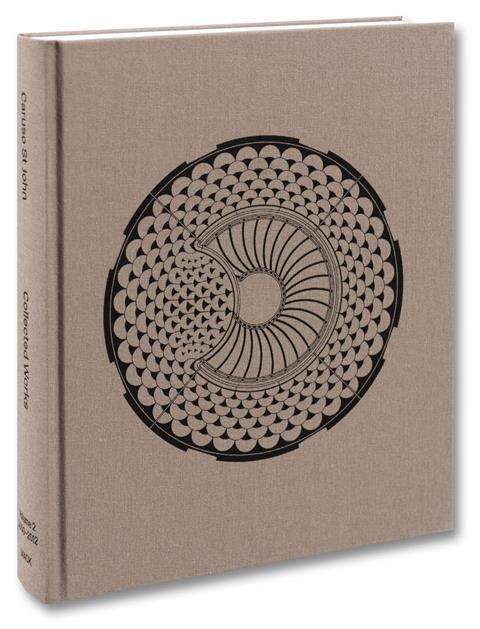

I can offer one opinion very quickly. Even if you have both their El Croquis volumes, I would counsel you to consider buying these beautifully produced and useful Mack editions, and saving up for subsequent volumes.

Although the Croqs make some attempt to situate architects’ buildings intellectually, the cumulative effect of the numerous more obliquely weighted interviews with Adam Caruso and Peter St John presented here, alongside a wide range of thematically relevant texts by, for example, T.S. Eliot, Lisle March Phillipps and Louis Sullivan, give the Collected Works a heft simply lacking in a more processional set of drawings and images. It gives a genuine insight into their motivations and interests.

The architectural scene in Britain covered by this volume saw the ascendency of a form of enervating not-modernism characterised by Caruso as nonetheless “informed… by the avant-garde formalisms of the early twentieth century.” What we might call the practice’s middle period was thus taken up with counter-proposals to this stifling and incurious uniformity. The Caruso St John of these years had an oscillating attitude to modernism, characterised initially by a qualified embrace, but then moving towards an increasing reliance on recovered historical critiques (from within the modernist paradigm, just about).

Knowing what we know now, it seems that a predilection for ‘peripheral modernists’, who regarded themselves as modern-in-continuity, like Auguste Perret, Adolf Loos and Josef Frank, admired by Caruso St John for their own sakes’, rather than as mere forerunners of whitened purity, could be indicative of latent classical tendencies. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves – Chiswick House Café (2006-2010), for example, is more subtly allusive, with a load-bearing travertine colonnade, than overtly imitative of Lord Burlington’s neo-Palladian villa.

It is altogether a Milanese cohabitation – Ernesto Rogers has some neat lines in a 1954 essay included in the book about being modern meaning “simply to perceive [the contemporary] within the order of all of history”, of not barricading oneself within an “enclosure of egotistical display”, and of architecture as a form of spiritual collaboration producing “perennial contemporaneity”. Well, it worked in central Milan, where Modernism has been house-trained by history to its and our great benefit.

Weirdly, given our indifferent and philistine culture in which architecture struggles to plead for its inherent value, the British architectural establishment always seemed keener to pick energy-sapping internal fights than advocate for excellence in plurality. Caruso and St John remark with irony that “some of our architect colleagues thought that we had crossed the dangerous line into historicism and pastiche” with their exquisitely refined interventions at the Sir John Soane’s Museum (2009-2012).

Presumably, these were the same prigs who bridled at their restrained and thoughtful use of colour and pattern at the V&A Museum of Childhood (2002-2007). It is probably more true that Caruso St John are (or were) simply in the mainstream of European modernism – it just didn’t seem so to Anglo-Saxon eyes.

It’s odd that some references are not made when they are so clear – the new crossing sanctuary for St Gallen Cathedral in Switzerland (2011-2013), with its beautifully simple but fiendishly technically complex undulating intarsia grapevines, elliptical steps and quadranted corners, feels like an homage to Rudolf Schwarz (1897-1961). In fact, there’s a curious lack of reference to the mid-century Germans who were busy thinking thoughts we now all regard as terribly fresh; Emil Steffann and his rubble churches, Schwarz and (only now just beginning to get his Anglosphere dues) Hans Dollgast.

This principled ethos of intervention, of the sheer enjoyment of materials, textures and forms, of reform in continuity, has been a core part of modernism’s practical apparatus from the beginning. In fact, modernism has been conceptually plural from the beginning – never mind what Corb or Mies said or didn’t say, still less what was meant by it.

Caruso St John’s work over the period covered remains contextually contingent and broadly modernist. Despite feeling that there is “no jarring sense of old and new”, Jay Merrick considered that their work at Tate Britain (2006-2013) didn’t project “relativist postmodernity or calculatedly suave historical pastiche.” A pared back architectural language deploying geometry, pattern and texture and sensitive to proportion seems like one perennially appropriate way of dealing with classical buildings.

Their straightforward love of building and materials and a reluctance to foreclose a freely intuitive experience of their buildings via over-intellectualised authorial interpretation is clearly communicated throughout the volume; the texts reproduced here are very much adjacent to the work rather than the keys to it. But there are also intimations of further, more traditional architectural developments.

Their work at Downing College, Cambridge, initially as much archaeological and restorationist as additive when we see it in this volume, leads to a formally classical proposition, the Student Centre, consented in 2021. Other, classical projects are in the offing; I look forward to seeing these realised and I agree with them that classicism is both valid and licit.

But this represents a little movement on from their conceptual focus on an architecture “before modernism, (which doesn’t exclude) modernism as another past that can be referred to” that characterises the work presented in this volume. I suspect that for some architectural puritans, and even some resentful classicists, this work will prove a step too far. In fact, there is no evidence in their current work of a commitment to architectural monogamy.

All the same, I do find it fascinating that an interest in continuity inevitably turns into a yearning for ressourcement. As Cardinal Newman said, “to be deep in history is to cease to be a Protestant”, so perhaps to be deep in architecture is to cease to be modernist?

>> Also read: ‘An insightful journey through a pivotal period in British architecture’

>> Also read: Adam Caruso on the impact of Liverpool’s pioneering Ellis Buildings

Postscript

Collected Works: Volume 2 2000–2012, by Caruso St John, is published by Mack Books

Giles Heather is a director and co-founder of Goldstein Heather Architecture

No comments yet