As the Royal Academy prepares to celebrate Herzog & de Meuron’s legacy, Michael Hodges gains a rare insight into the pair’s working relationship and how they are handling the backlash on two high profile projects

Swiss architects Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron - responsible for some of the most noteworthy building projects of the past 40 years, including Beijing’s Bird’s Nest Stadium and museum of visual culture M+ in Hong Kong - are celebrating their achievements this summer at the Royal Academy. A wide-ranging show, it features displays of their methods, materials and technologies, co-curated with Herzog and de Meuron themselves.

Ahead of the show Building Design had a rare opportunity to talk to de Meuron at the duo’s headquarters in Basel, the Swiss city where the architects met as seven-year-olds at primary school in 1957. De Meuron still remembers that first encounter: “It was our great luck that we grew up a quarter of a mile away from each other and went to the same school,” he says. “That’s interesting to me spatially. At that time, the radiuses of children and families were quite small. It was much more neighbourhood-related. I went to one kindergarten; Jacques went to another kindergarten, but then we went to the same school and we were together. We don’t emotionalise it. We don’t make it nostalgic or kitschy – but this is how it is.”

The young friends made Lego models and played music together but the pivotal point, the moment when all the triumphs that lay ahead first came into view, was when they encountered the roller coaster at a summer fair. “We were fascinated by the architecture and the technology of the roller coaster, together we tried to understand that.”

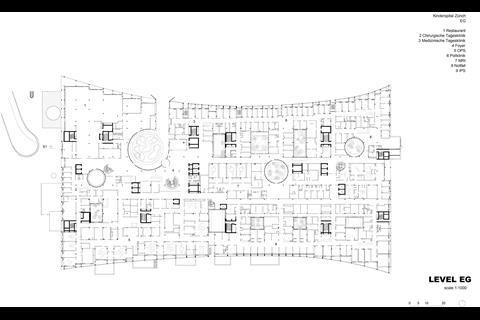

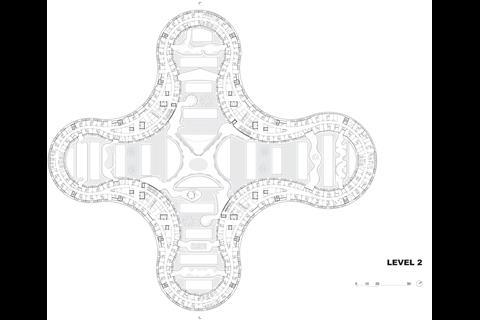

Six decades on, their triumphs in London alone include the recently completed Royal College of Art campus in Battersea and Tate Modern. Alongside these “event” buildings they are responsible for some innovative health projects, such as the soon-to-be completed Children’s Hospital in Zürich, hospitals in Denmark and San Francisco and here, on the outskirts of Basel, REHAB – the centre for recovering spinal injury patients. Low-rise, heavily reliant on wood and emphasising access to green space it is, in some ways, the template for a holistic approach to healthcare buildings that will be one of the focuses of the Royal Academy show.

But just as the pair prepare to be celebrated, the first signs of a backlash are emerging. In Paris the 48-storey Triangle, planned to rise 180m above Boulevard Périphérique for the Paris Expo, has been caught in the debate about whether Paris should remain a low-rise city. Now the council has decreed all new buildings must not exceed 37m. In London a public campaign has been launched against a proposed 15-storey development above Liverpool Street station. There is much to talk about …

Why does your friendship and professional relationship work so well after all this time?

There’s no recipe. That’s just how it is, that’s friendship. It is emotional but it is also very rational because we understand each other. We have different talents and different weaknesses, and we accept our own and we accept the other’s. This is the best way to collaborate as humans in the end.

Do you see any connection between the objections to Liverpool Street and the Triangle?

The two are different but I think you can link them. They are things that are visible, of course, so they are more seen and perceived. If people have issues of height, or mass, then they can point to Liverpool Steet as an example that can be criticised. I have no problem with that at all. Architecture is something public – we are in the public with everything we do.

Very little architecture is mobile, on wheels, or temporary; most architecture is still rooted and is there for quite a lot of time. So, yes, those projects are being discussed and I think it’s right that they’re being discussed. Those are issues that concern us as a society and as, let’s say, professionals.

But London is, for me, a different issue [to Paris]. It is also visible, but you build on top of something and the massing is completely different. The relationship to the existing is something different than in Paris Expo, where you have quite a wide field. Having a debate on Liverpool Street station and how heritage is affected is important, it is good to open up a discussion.

And Paris?

Paris is beautiful, this homogeneous Haussmannian city as it’s been called. But then you have the Boulevard Périphérique, and it was always our belief that you can, at certain points, have a higher building. Not everywhere, but at some points. You have also a very different scale with the Boulevard Périphérique, which is something contemporary, something that came after World War Two. If you say Paris is the idea of a city of the second half of the 19th century, the Boulevard Périphérique is an American idea of the modern city, created in order that cars can move fast. It’s like two different concepts of the city that come together at the site.

The Tour Triangle is interesting, it has to be sustainable, not only in its construction, and its energy consumption, but also in its concept

And the Tour Triangle is interesting, it has to be sustainable, not only in its construction, and its energy consumption, but also in its concept. The concept there was that the masterplan should be three buildings. We said “why do three buildings? If we can, we could do it in one building. So the three monofunctional buildings, why not do one building with all the functions within it?” This is what the idea was. You could say it’s stupid, but it’s very simple. And of course, it has an iconic form, the triangle.

More generally, what are the difficult issues when building in cities?

You must think about what it means to build in the existing fabric. How much at the end is a question of dimensions; for instance, height in Paris. Then, of course, there is concrete, all that material stuff is also an issue. Most of the projects cannot work, cannot be built, without concrete. So there we have a greater problem as a society as a whole and we definitely have to find a better way to build than with concrete, and as fast as possible. It is the cement, by the way, which is the problem because it is so energy-consuming and creates CO2.

Do you mind the public campaigns, do you take them personally?

We also have campaigns in Germany with the museum [of the 20th Century, in Berlin]. There are issues. What is the museum for? How much energy consumption will there be? Of course, you can discuss and debate those issues. In Paris, there were always also two different opinions. Many think it’s beautiful, others think it is a problem, because of the height. We have to cope with it, we have to understand why. The Expo wanted to have a building; they were also interested in having something which has this iconic form.

In Liverpool station, yes, we have to think about heritage, we have to think about daylight in the concourse and we have to think about massing

To answer your question, how do we deal with such criticism, we cannot escape it, believe me, and we try to speak openly about it. If the debate is on a good level and it’s not just bashing us then I don’t have a problem with that. The debate is subtle, you can ask about heights in Paris and does it affect Montparnasse? Well yes, it does, it’s big. But I don’t think this building harms the homogeneity or the beauty of Paris. In Liverpool station, yes, we have to think about heritage, we have to think about daylight in the concourse and we have to think about massing.

Does London still feel like a great place to create?

Absolutely. London is interesting, I don’t need to praise London, it’s a world city, with all its elements and qualities, but also sometimes not so pleasant places, like every city has. We think it’s a great place to think about what is a city, how does a city develop? Also, it’s now outside the EU, so what does that mean, economically, socially?

If a future UK government expanded the programme of new hospital building, would you want to be involved?

To be involved and have an input into what excellence can be in the 21st century hospital? Yes! To build a hospital would be great because we know that healthcare is a problem in England. We are not just architects who do a nice building, we are interested in how to think about healthcare as well as the architecture. I think also with our healthcare projects we have been thinking, what is healthcare? What are patients? How is it with this healthcare system, which becomes more and more expensive, and no one can pay it, how can you deal with that? So I think we have a contribution to make. We also have a big project in the US, a project in Zurich, the one in Denmark. Healthcare is important, of course, socially and economically, so that would be fantastic. I don’t know if the government is ready for that, but it would be great to start the debate on that.

>>Also read: Paris bans tall buildings after Herzog & de Meuron tower backlash

>> Charles Saumarez Smith: Why is Herzog and de Meuron submitting this bonkers proposal for Liverpool Street?

Postscript

The Herzog & de Meuron exhibition opens at the Royal Academy on 14 July and runs until 15 October. The exhibition will be arranged in a sequence of three spaces that together explore the ideas and processes in the making and experience of architecture.

No comments yet