The RA has mounted an exhibition that tells an intriguing and judicously edited story about the renowned Swiss practice, writes Daniel Elsea

Making an exhibition is as much an exercise in storytelling as it is in editing the telling of a story. And the new exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts on Herzog & de Meuron proves this point.

What is intriguing about it is how little of the practice’s work is covered when one thinks of the expansive oeuvre of Herzog & de Meuron. Their output is prolific. I count 594 projects on their website; the practice boasts 600 architects on its payroll. Yet this exhibition gives a light touch overview of fewer than 30 projects, and then going in depth into just a couple of those.

This is not a retrospective. And that in itself is a mark of quiet confidence. The temptation, even in the limited space of the RA’s Gabrielle Jungels-Winkler Galleries, would have been to go full throttle as Foster’s current exhibition at the Centre Pompidou has done.

Across the three rooms where previous shows of Rogers and Piano have been hosted, the first gallery is the one where the most lingering happens. It is dominated by the kabinett vitrines of the the practice’s Basel studio. They are arranged à la full bibliothek, each set full of models, maquettes, material samples and small screens depicting films. It’s a pleasurable cross-section of an architectural portfolio and the making of.

An augmented reality interface is incorporated as well. It’s a bit of fun. The scale of these cabinets of curiosities reminds one of Mike Nelson’s recent show at the Hayward. Here’s big archive, monumental, a little bit messy, and full of details to be discovered. As a piece of exhibition making, it’s the best part of the exhibition.

In the same room, large format prints by the German artist-photographers Andreas Gursky and Thomas Ruff hang on the walls, illustrating different buildings the practice has designed but through their artistic lens (read: not that of an architectural photographer). They show the everyday life of buildings.

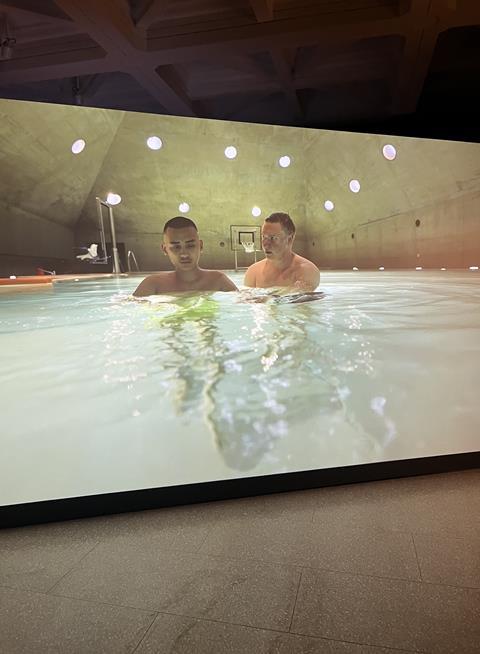

In another room, a large format film shares the stories of patients at the Basel Clinic for Neurorehabilitation and Paraplegiology. It is poignant. This wonderful project (this was the first time I’d heard of it) is shown through the eyes of the filmmakers Bêka & Lemoine and the lived experience of patients.

These portrayals of architecture by other producers of visual culture are examples of architectural storytelling at its most successful.

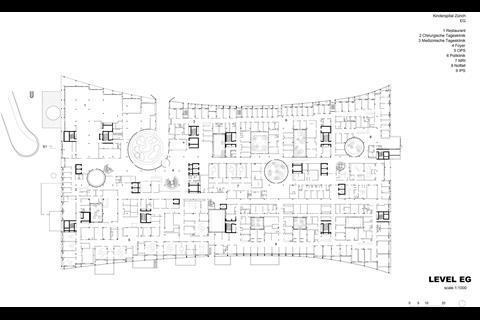

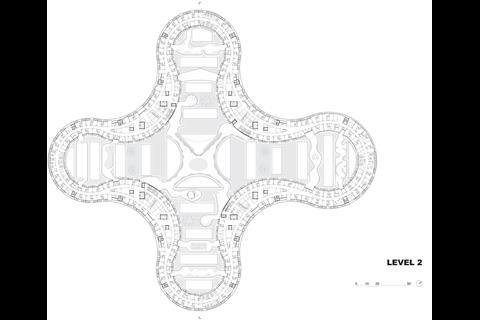

From here, the remainder of the exhibition takes a tight focus on spaces for healing. A whole third of the space is devoted to just one project currently onsite: the Kinderspital (Children’s Hospital) Zürich. It has parallels with the Basel clinic, built more than twenty years ago, in its un-hospital approach to hospital design.

They shed many of the aesthetic elements so typical to clinical spaces. There is generous use of timber, accented with exposed concrete. No eggshell blue or clunky medicalised corridors. Instead, there are wide horizontal floor plates punctuated with scruffily landscaped courtyards, a blurring of indoor/outdoor, meandering internal streets.

These design choices come together to create what seem to be two really wonderful buildings for healing. So refreshing. It makes one wonder why society can’t incorporate this kind of approach more widely into the design of hospitals. If any space necessitated humanity, craft, beauty, it is the places we go to to recover our bodies (and our minds). Here’s a new manifesto: de-medicalise medical spaces as much as possible.

That so much of the show is dedicated to the theme of health is curious in itself. It comes at the expense of learning more about Herzog & de Meuron’s more famous buildings. All those museums for one; every city seems to have one. (I was really wanting to see more material about M+ Hong Kong, probably my favourite building of their’s), but this cultural colossus gets just one corner of one shelf in one kabinett.

So, why the focus on health? Are they trying to position themselves for a certain market of work? Or is it that after the global pandemic, it is the typology of the hospital which is so in the consciousness right now? What is certainly evident is that they are very proud of these two buildings. And rightly so.

>> Also read: Pierre de Meuron on Liverpool Street station, Paris’ Triangle and dealing with criticism

>> Also read: A new campus for the RCA by Herzog & de Meuron

Postscript

Herzog & de Meuron is on view until 15 October 2023 at the Royal Academy of Arts

Daniel Elsea is a partner at Allies and Morrison

2 Readers' comments