Ben Tosland considers how a new publication sheds light on the layered political, cultural and climatic contexts behind Africa’s modernist legacy

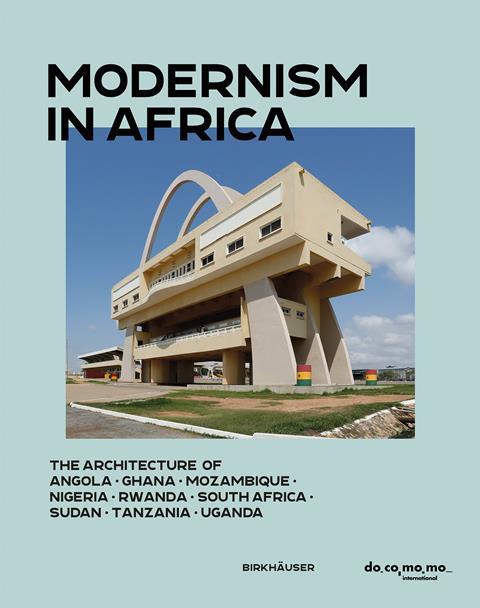

Modernism in Africa has the appearance of a coffee table book, but it offers a serious and compelling chronicle of architectural modernism across a select group of African countries. Many of the buildings covered respond sensitively to climate and were constructed during a period of independence, political transformation and economic development. They embody not only a distinctive architectural language, but also the ambitions and complexities of post-colonial nation-building.

The book opens with critical essays by Ola Uduku (professor of architecture and head of school at Liverpool School of Architecture), Uta Pottgiesser and Ana Tostoes, as well as an interview with photographer Jean Molitor. It is structured country by country, with short essays on selected buildings by a wide range of contributors – many of them architects and academics with expertise in the locations they cover. This approach offers a valuable snapshot of current scholarship on African architecture and provides a useful reference point for editors and researchers alike.

Richly illustrated with contemporary photographs by Molitor, and complemented by up-to-date floorplans of each building, the book also makes extensive use of archival materials.It provides a record of a building style that was at once a symbol of Western intervention and colonial authority, albeit one that was also later embraced by post-independence governments as an expression of national identity.

Each nation experienced these elements differently – the legacies of this are understood in their own local contexts rather than on a pan-continental scale. Birkhäuser published the book in conjunction with Docomomo, the international conservation non-profit organisation that highlights, documents and conserves buildings of the modern movement, many of which are now closing in on their centenary years.

The range of projects presented is impressive. From hospitals to offices, housing to cinemas, and a focus on educational buildings, Modernism in Africa presents building types shaped by the economic and political narratives of the time. While the broader notion of modernity beyond the built environment is not explicitly foregrounded, it is nonetheless a persistent undercurrent in the material.

Across the continent at this time, with the construction of new towns and the introduction of town and city plans, much was made of industry. Within this narrative, industrial buildings are overlooked in the book. It is a missed opportunity to assess such an important building type, given the focus on engineering, aeroplanes, boats, grain silos and the ‘machine aesthetic’ in the development of modernism.

In the post-independence period, and against the backdrop of the Cold War, African nations were subject to significant economic influence from both the eastern and western blocs – a dynamic explored in Łukasz Stanek’s seminal Architecture in Global Socialism. Many international companies established factories and outposts across the continent.

In the aluminium industry, for instance, Western firms such as ALCAN built facilities strategically located near ports, transport infrastructure or raw materials, and drew on local labour. The resulting structures were often notable examples of modernist architecture.

Ultimately, this book fits with the wider literature that has developed around the continent in the past decade or so. From DOM Publishers’ guidebooks to the continent – which took its editors, Philip Meuser and Adil Dalbai, over ten years to compile – to the V&A’s Tropical Modernism exhibition and accompanying book by Christopher Turner, it is a welcome addition to the literature.

It bears similarities in form and style to African Modernism: The Architecture of Independence, edited by Manuel Herz and published in 2015 by Park Books, but differs through its focus on documenting and conserving ‘buildings, sites and neighbourhoods of the Modern Movement’. The depth of research and writing into this subject area is only going to further advance in the next decade, with a major exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York planned for 2026 on West African Modernism.

As stated at the outset of the book, this is a provisional overview, not a comprehensive survey. After the MoMA exhibition, there will be considerable revision of the base histories identified here. This is the act of history – understood as a verb, as someone like E. H. Carr would have it. Carr argued that history is not a fixed record of the past but a continuous dialogue between the present and the past, shaped by the questions each generation asks of it.

In this sense, the narratives presented in Modernism in Africa are provisional, open to reinterpretation as new research, perspectives and exhibitions reframe what is known and valued.

When the V&A’s Tropical Modernism exhibition opened in 2024, reviews noted that its ambitious title was not matched by the relatively narrow scope of its content. And while this may have been the case, every incremental addition by high-profile institutions and publishers helps to draw attention to a still relatively overlooked body of architecture that played such a significant role in state-building and modernisation across the African continent – a legacy entangled with the complexities of colonialism, modernity, identity and nationhood.

>> Also read: MoMA’s exhibition illustrates the rich legacy of South Asian modernism

>> Also read: Remembering Doreen Adengo - an architect with a passion for African urbanism

Postscript

Modernism in Africa: The Architecture of Angola, Ghana, Mozambique, Nigeria, Rwanda, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda is edited by Uta Pottgiesser and Ana Tostoes , and published by Birkhauser.

Ben Tosland is an Associate at Montagu Evans in the Historic Environment and Townscape team. He is a part-time lecturer at New York University (London). His book Who Are Godwin and Hopwood? was published in 2024 by Birkhäuser.

No comments yet