One small Ugandan practice reaches into the past to inform a contemporary monastic complex in the south of the country, writes Ben Flatman

The current generation of architects are among the first in the long history of our profession for whom an ecclesiastical commission is probably neither expected nor particularly sought after. This shift away from the sacred may have crept up on us largely unnoted, but it’s still worth reminding ourselves that it represents a radical change to the architect’s traditional role.

The very foundations of architectural practice lie in the masonic traditions of cathedral and church building. Any aspiring architect from the Renaissance through to the late 19th century would have expected to design a church. And as recently as the 1960s prominent practices such as those of Basil Spence or Gillespie, Kidd and Coia were as well known for their religious buildings as anything else they produced.

Today in the UK and much of Europe, such commissions are increasingly rare. Architects are focused almost exclusively on the secular. Skyscrapers and shopping centres have taken the place of cathedral spires and churches on our skylines, as consumer capitalism has usurped the role of religion in most of our lives. This move away from the religious to the profane also means we have fewer opportunities to explore the spiritual dimension to building, which was historically a key driver behind many architects’ sense of vocation.

Have we therefore lost something as a profession that we haven’t quite yet processed or compensated for? Does it matter that few of us will ever get the chance to design a devotional space, with a brief far removed from maximising the efficiency of a residential floor plan? Arguably, this huge cultural change left a significant gap in the life and work of many architects – denying us that opportunity to work on the types of contemplative spaces once offered by a church commission.

But it would also be to take an entirely Eurocentric view to imagine building churches is out of fashion globally. In Africa, with more Christians than on any other continent, church construction is booming. And, for one practice in Uganda, the continued strength of an African faith-based culture has provided a remarkable opportunity to design a new monastery in the south of the country.

The community at Our Lady of Victoria Monastery in Kijonjo, is a Cistercian Trappist order, founded as an offshoot of the famous Koningshoeven Abbey in the Netherlands. Originally established in Kenya in 1956, the monastery was rocked by the rioting that followed the 2007 presidential elections and moved to Uganda in 2008.

Just in case there was any doubt about the direction they wanted him to go in, when Localworks founder Felix Holland was approached to design their new monastery, the brothers from Kijonjo presented him with a book on the history of Cistercian architecture. “The monks sent me a brilliant book called ‘Cistercian Europe – Architecture of Contemplation’. Everything I know about Cistercian architecture stems from this book,” says Holland.

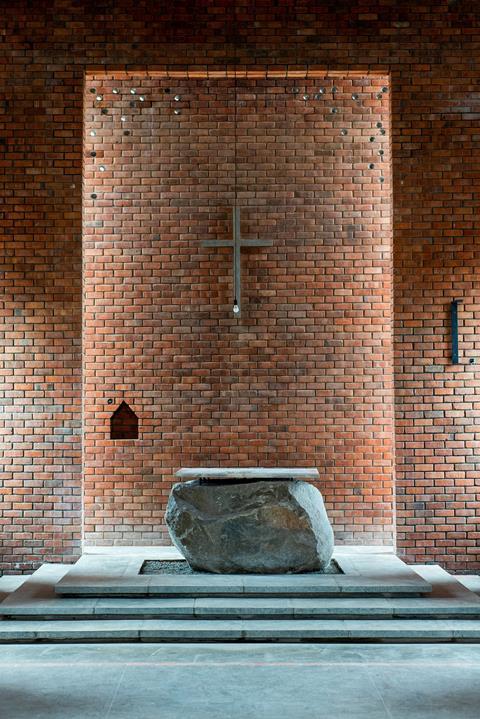

The Trappists emerged from the Cistercian order in the 17th century, adopting a more austere interpretation of the Rule of Saint Benedict. Cistercian architecture itself had grown out of the aesthetic preferences of Bernard of Clairvaux who believed that banishing superfluous ornamentation would help create a pure space without visual distractions, so that the monks could focus on a life of prayer and religious devotion. Bernard also bequeathed a preference for exposed masonry, without plasterwork, which gives Cistercian monasteries an added sense of honesty in terms of materials and finishes. This rich built heritage is notable for producing monasteries such as Le Thoronet Abbey in Provence. It’s a tradition that easily lends itself to modernist reinterpretation and has heavily influenced many architects from Fernand Pouillon to John Pawson.

But beyond the legacy of stripped-back monastic architecture there was also the liturgical tradition and daily lives of the order that Holland had to understand in order to design for them. During the early stages of the design process, he spent 24 hours with the monks, following their daily rituals. “The experience was very intense, with seven services each lasting about 45 minutes; the first one at 3.30am, the last one in the evening at 8.30pm.”

Holland describes how the monks sit in two groups facing each other and recite religious texts in a “question and answer” style. Between the services they retreat for meditation, prayers, or to work in the monastery’s farm. “They don’t talk much. Even during meals, which are taken together, one of the monks reads to the others, so even then there is little talking. It was incredibly important for me to have experienced this because it helped me understand their daily life and directly impacted on the design,” Holland tells me.

Localworks also took inspiration from a number of monastic projects elsewhere, including historic buildings such as the floorplan of the Alvastra Abbey in Sweden and the proportions of the church of the New Melleray Abbey. More recent influences were the Stanbrook Abbey by Feilden Clegg Bradley and the Tautra Monastery in Norway. “We wanted to design a ‘contemporary tropical monastery’ that was still firmly rooted in the tradition of the Order,” says Holland.

As a result of this incremental rather than revolutionary approach Holland saw it as more interesting to “continue the story”, and “pick up the thread where it was left” rather than seeking to “reinvent the wheel”. He believes this approach is most evident in respecting the typology and proportions of the monastic church, especially the barrel vault. He highlights the traditional proportions of monastic churches – tall, narrow, and long. The Kijonjo church is 28m long, 7m wide and 11m tall.

In fact, Holland describes almost every design consideration as either based on the Cistercian tradition or on climatic considerations. As the project is only a few kilometres south of the equator the church is closely aligned to the equatorial sun, the changing path of which can be experienced throughout the year inside the building. There are sun catchers in the eastern wall which are illuminated in the mornings of solstice and equinox days. Glass bottles, embedded in the brick masonry walls and vaulted roof, direct sunlight into the church at midday; and there is a rose window that casts a circular spot of direct evening light into the church during the late afternoon services. “Apart from rooting the project into its tropical location, a secondary aspect here was that we wanted to use the opportunity of designing for users with such a rigid, repetitive daily routine – we know to the minute how the building is being used across the year – in such a way that they experience the seasons from inside the church,” says Holland.

Complex environmental and operational constraints run through the entire project. It is an extension of an existing monastery building from a decade earlier which suffered from poor workmanship and had been damaged in a recent earthquake. Localworks’ design therefore had to integrate old and new, all while the brothers continued to live their daily lives within the site. Consideration of a particularly high water table (the project is located in a wetland setting not far from Lake Victoria) resulted in the entire project being raised on to an inclined plinth. A secondary roof that hovers above the barrel vault collects rainwater, produces electricity and shades the building. All the new buildings are also designed to be passively ventilated, with cross-ventilation, ventilated ceiling voids, reflective roofing materials and shaded windows, helping ensure a comfortable indoor climate throughout the year.

The choice of materials was also dictated by context. “Uganda is the land of clay,” states Holland, “and fired clay bricks are available almost everywhere in the country.” The design makes use of bricks sustainably fired with coffee husks. “As a material, it was well suited to the project because it lends itself so well to the Cistercian principle of ‘material only’, is widely available, ages well and is easy to handle.” For the church a complex system of reinforced masonry was used, as the barrel vault geometry has huge moments that needed to be brought down through the inclined buttresses. Building these buttresses in brick allowed for the architectural expression of exactly how the loads come down, by gradually increasing their thickness and depth towards the ground.

Holland is as conscious of the cultural sensitivities around this building as he is of the environmental ones. Christianity has deep roots in Africa, going back to the first century AD in Egypt. And the ancient rock-hewn churches of Ethiopia stand as some of the most striking Christian architecture anywhere. But Catholicism only arrived in Uganda in 1879. “What is African about the Cistercians?” he ponders. And, what makes this project specifically Ugandan? He points to the keen awareness of the locality in as far as material, climate and craftsmanship are concerned, and views “mixing” this contextual methodology with the Cistercian tradition as the correct approach for the site.

>> Ben Flatman: Navigating the legacies of colonialism in East Africa

>> Also read: An architect’s guide to surviving the rule of Idi Amin

>> Also read: Patrick Lynch’s Inspiration: St Peter’s Church, Klippan

Holland also openly acknowledges the personal complexities of working in Africa as a European. “I don’t define myself as an ‘African architect’, nor as a ‘European architect working in Africa’, instead I’m a contextual architect working in Uganda, striving for sensitive, harmonious and appropriate buildings.” With a growing and impressive portfolio of work, delivered by a team of predominantly Ugandan staff, it is undeniable that Localworks is forging an excitingly inquisitive path through the African architectural landscape.

When I asked Holland whether designing a religious building had “filled a gap” professionally in terms of providing an opportunity to explore a typology that few architects now get the chance to engage with, he was emphatic. “Yes, although perhaps this applies somewhat less to architects practising in Africa given the importance religion plays on this continent. I wouldn’t be surprised if this wasn’t the last church in my career, although perhaps a monastery may indeed not come again!”

No comments yet