In response to the Fawcett Socety’s independent report for the RIBA, Sumita Singha asks why so many women in architecture still struggle to be valued and recognised throughout their careers

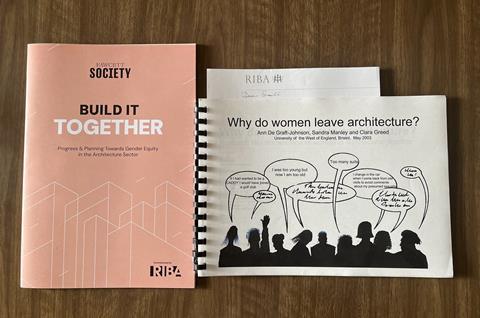

Twenty-three years ago, RIBA’s Equality Forum, Architects for Change, commissioned a report, Why do women leave architecture? The report from the University of the West of England researchers had 174 respondents, including some men. In 2002, there were 38% women students and 13% women architects – a figure that had stayed stable for a good few years.

I had set up Architects for Change reactively after it had been announced that Women in Architecture, which I had been chairing, would become a special interest group. ‘Being a woman wasn’t a special interest,’ I had written back to RIBA. I was then running my practice, with a small child and another one on the way.

So, after decades of campaigning, legislation and women’s marches, I wanted some good news of progress with the RIBA-commissioned Fawcett Society report on Gender Equity in Architecture. The 635 respondents have come from different sizes of practices (and not just chartered), so it gives a picture of the profession.

It is a wide-ranging report with 47 ‘blue sky’ recommendations for the Institute, employers and practices, and policymakers. Twenty of these apply to RIBA, and they will be tackling 10 in the first year, with some actions already underway. While I’m pleased that my 2023 book, Thrive: A Field Guide for Women in Architecture, has been referenced twice in it, I was dismayed to read that not much has changed in the profession in more than 20 years.

The 2003 report outlined issues which could be grouped roughly into pay issues, working conditions, lack of progression, ‘macho’ culture and lack of returner training. The 2025 report uncovers similar issues (with a few updated terminologies) – motherhood penalty, gender pay gap, gender health gap, old boys’ club and sexual harassment. Like the previous report, the actions are solely focused on the UK. There are three categories of recommendations in the latest report:

- Working as an architect

- Pay and progression

- Institutions leading the change

Today there are more women architects in the UK – 33% (approximately 25% of whom are chartered) and around 50% women students. But despite 50 years of the Equal Pay Act, over half (54%) of survey respondents had discovered that a male counterpart at the same level was earning more than they were.

The gender pay gap in the UK is worse than the OECD average, while within architecture, the pay gap of 15.4% has remained the same since 2018 because women take up more of the lower-paid jobs. It is to be noted that only 10 UK practices and organisations (including the RIBA) were required to report because they have more than 250 employees.

The report says that workplaces have failed to respond to the health needs of women, with one in ten women leaving due to menopause and long-term health conditions. Over a third (35%) of respondents had experienced sexual harassment at work. Half (50%) of all women respondents had experienced bullying at work in the architecture profession.

In my introduction to the four-volume publication Women in Architecture (Routledge, 2018), I talk about the four filters that lead to the loss of women in the profession:

- Valuing of men over women (universal gendered filter)

- Devaluing of the profession (professional filter)

- Discrimination against women in the workplace (employment filter)

- Discrimination based on intersectional characteristics such as ethnicity, socio-economic class and disability (intersectional filter)

It is obvious that these filters continue to operate. Comparing detailed statistics from ARB, RIBA and the Architecture Council of Europe (ACE), I see that men still outnumber women architects – 64% to 33%¹. While women and men in the age range 31–40 years make up the largest proportion of architects, over 5% of men keep working well into their 70s, while women gradually filter off to less than 1% at the same age.

These are similar findings to the ACE 2024 report, which showed that older women gradually stop working while men continue, demonstrating the valuing of men over women. The ACE and ARB reports also show that younger women are responsible for increasing gender parity in numbers, but do these women progress to higher levels in their practices?

Due to the higher numbers of women architects and better reporting, the effects of discrimination appear to be magnified. Discrimination based on intersectional characteristics has been widely described in the Fawcett report. But there should never be any excuse for bad behaviour.

In terms of the devaluing of the profession, income for architects has decreased over the years, which has had a knock-on effect on women. A culture of long hours and low pay is rife in the profession, with low profit margins. Twenty-five years ago, a chartered architect aged 38 years earned over £67K, while in 2024, they earned £48K.

While the unemployment rate for architects is less than 1%, overall incomes have gone down². Interestingly, in 2024, older architects (50 years and above) saw their earnings grow by 12%, whereas age groups under 45 years faced stagnation or decline (these are often parents of young children).

Given the rate of growth, we might get to 50% women architects by about 2054

According to the Fawcett report, 84% of women received less support after returning from maternity leave, while women with two children took home 26% less than their counterparts without children. The UK has the fourth-highest childcare costs of any OECD country, but parents might still be paying one-fifth or more of their salaries for childcare, so is it any wonder that they prefer to work part-time?

The result is the pronounced gender pay gap, because women are more willing to take up caring responsibilities as well as the lesser-paid part-time work. When income is down, things that are seen as ‘nice to have’, such as a foucs on EDI, tend to fall away. So, will the other 27 recommendations from the report be taken on by practices and members?

Given the rate of growth, we might get to 50% women architects by about 2054. But that might not necessarily improve the quality of women’s working lives. If we compare architecture to other cognate professions in terms of numbers of women, architecture lies below town planning and above surveying and engineering.

So, we are talking more about retaining women in architecture, and not just increasing numbers. Retention of employees is more cost-effective for everyone. Mentoring and support, including allyship, during both education and practice is helpful for the retention of women, and that support can be given by both men and women.

That, along with returners’ courses to help those who have taken time out for various reasons, has been really successful in the past. And to this end, visibility, voices and valuing of women architects will continue to be important to the profession.

Postscript

Sumita Singha is a chartered architect, author, educator, and RIBA Board Trustee, writing in an independent capacity.

¹ The rest being non-binary or those who did not reveal their genders.

² https://www.ribaj.com/intelligence/employment-and-earnings-falling-salaries-prompt-deeper-study-of-income-differentials

No comments yet