Architects are constantly producing works of art but often just don’t realise it, argues Karl Singporewala

“That drawing looks good, Karl, but is it good enough to hang in Saatchi?”

So said my part 2 architecture professors (the effervescent Christopher Pierce and Chris Matthews) as they waded their way like hunters through my weekly pin-up, putting Xs through certain drawings and ripping others entirely off the wall. This was the weekly ritual, a piece of theatre we put on for other students, which I sadistically enjoyed.

Whatever was left on the walls made it through to the next week, and so on. But what about the hundreds of drawings which did not make the cut? All that time, effort, production and, above all, printing costs… where did it all go?

I used to collect up the “rejects” and take them to a couple of small, now defunct, high street galleries; one in Brighton and the other in Leicester. Both relied on local artists to fill the walls (no sale, no fee). In this way, I sold my first few drawings for pennies and found my first patrons. This arrangement helped to cover those university printing costs and even one or two student union pints.

Then I got the opportunity to display a drawing on the London Underground at Euston station, so I asked my professors if I could use one of the drawings that was still up on the wall! They approved, even though Euston was not quite the Saatchi Gallery. But the drawing they recommended I use was my most ambiguous, least building-like drawing on the studio wall.

When I questioned their suggestion, pointing out that I wanted to be known as an architect, they simply replied, “this is architecture”. I was unconvinced by their reply but followed their advice.

To make sure no one would mistake me for an artist, I even typed the words “this is architecture” on the poster, like some ritualistic mantra, hoping it would stick. It worked and I started to get a taste for exhibiting.

That is when I found out about the Royal Academy of Arts Summer Exhibition. I submitted my diploma work in 2007 while I was still completing my part 2 course and was lucky enough to have two pieces selected and hung.

My first ever varnishing day turned out to be a blast, and then I got to meet the Royal Academician who selected and hung my work that year, the professor for architecture at the RA, Ian Ritchie. Next thing I knew, I had a job at Ritchie’s office – and that’s where I spent the next 10 years of my career.

To call this place an architecture office is a disservice. This place was like NASA, with people/teams sitting around thinking “stuff” up. Patents over here, “world firsts” over there.

We got to work on multiple building projects at once, and then there were the little gems: a sundial, a fountain, a plane, an illusion, a colonnade, a gilded telephone box celebrating 25 years of Childline, and of course a monument or two.

And then there were the other artists that turned up occasionally. “Karl, let me introduce you to [insert name of amazing contemporary artist here]”, Ian would say. Being exposed on a daily basis to work by David Mach, Barbara Rae, Norman Ackroyd, John Hoyland and of course Ritchie himself, was all inspiring.

One of my favourite encounters was when I turned up at 8am one morning to find a completely unannounced Tim Shaw camping out in the workshop. He was smoking huge leaf-shaped pieces of card as part of one of his haunting sculptures of the Green Man.

Why was he there, you ask? Well, he just needed a base while he was in London for a couple of days.

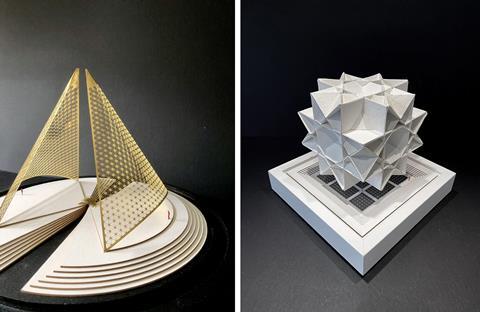

Ritchie’s art world exposure obviously influenced my own artwork, but it was the studio’s new workshop which provided me with a sanctuary. He genuinely put a laser-cutter in my hands and said, “go play”.

Using architects’ “tools” like laser-cutters, 3D prototyping and even just straight-forward good old fashioned CAD became the base medium for exploring ideas, materials and narratives – I never made a model of a finished building.

In terms of creating my own artwork, which tends to be more personal in nature and embellished by personal circumstances, it is always the open exhibitions like the RA Summer Exhibition and the Royal West of England Academy of Art (RWA) Autumn Exhibition which give me the opportunity to test ideas, techniques and hone my craft – and of course a place to sell and be hung alongside some of the best names in British Art.

Through the open exhibition system, I have learnt two key elements which govern my practice:

1. Architects put pen to paper every day creating sketches, doodles, details, patterns, compositions. Ask yourself, “is it good enough to hang in Saatchi?” If you think so, put it in an open exhibition and go from there. This is the primary piece of advice I give to every architecture student I meet.

2. No art collector wants to buy a plan or elevation of a building they don’t know. Collectors want to own something that speaks to them personally, something that makes them stop and look at it every time they pass by it. Generally speaking, the stage 4 ground-floor GA plan of your recent visitor centre is not going to cut it.

Over the years, the open exhibitions, have led to invited exhibitions, international tours, and public collections. In fact, ten years after completing my RIBA Part 2 course, I was able to invite my university professors to the Saatchi Gallery London, to see my art work hung next to the late great Keith Haring.

A particular recent highlight was having my charred study model of the destroyed Notre-Dame spire hung at the last minute in the RWA major exhibition titled ”Fire: Flashes to Ashes in British Art”. The exhibition included work by Mat Collishaw, Jeremy Deller, Susan Hiller, Aoife van Linden Tol, David Nash, Cornelia Parker and Tim Shaw, as well as historic artists ranging from Joseph Wright of Derby to Stanley Spencer and JWM Turner.

There are some other key institutes that promote the “artwork” of an architect as a pure art form. These include Drawing Matter (they had a great exhibition with the V&A on the history of architectural models at The Building Centre earlier this year) and cool art collective organisations such as ArtCan (which was founded by Stanton Williams associate Kate Enters).

There is also the wonderful annual art auction 10x10 by the architecture charity Article 25. I donate an artwork every year and have done so since its inception.

The competition between the architects and artists is great, although I do sometimes get “outsold” by the latest Anthony Gormley sketch. But, hey, it just makes me want to try harder and above all it’s for a cause close to my heart.

Gormley once made a good distinction between the two arts of sculpture and architecture. He highlighted that architecture deals with “social wellbeing, human-scale and how light can penetrate form” while sculpture “acts as a witness, holding human feeling and thought and inscribes it within geological time”. The artwork I create sits in the interdisciplinary liminal zone between these two places.

Sometimes I call myself a sculptor, but really, being: an architect, is quite enough.

Postscript

Karl Singporewala is an artist, architect and co-director at Barbara Weiss Architects. His art work is held in private and public collections world-wide.

7 Readers' comments