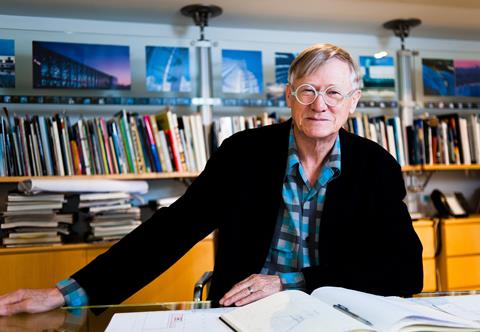

Sir Nicholas Grimshaw, who has died aged 85, helped shape British high tech with buildings that embodied structural clarity, adaptability and a spirit of optimism

Sir Nicholas Grimshaw has died at 85. He leaves behind a string of buildings that helped to define British high tech, derived from a design philosophy centred on structural clarity and adaptability.

He also laid the foundations for a practice that has since grown far beyond what he envisaged. Grimshaw is now much larger and more global than it had been under his leadership, yet it still draws on his ethos. The focus on how things are made and on structural honesty remains.

His family history included engineers as well as artists, and he said that he spent hours as a child making things. The boy who loved Meccano, tree houses and boats scaled up those instincts. You can trace that hands-on spirit throughout his career.

He studied at Edinburgh College of Art and then the Architectural Association. His path ran close to the 1960s avant-garde, but he took a more grounded approach.

Grimshaw’s earliest project was a now-demolished service tower for a student housing block. Responding to a commission from the Anglican International Student’s Club to convert six 19th-century terraced houses into student accommodation, he devised a spiral of fibreglass bathroom pods set on a helical ramp behind the terrace.

The pods were made by a dinghy manufacturer, the central steel frame acted as a crane during construction, and Buckminster Fuller came to see it. As Peter Cook, who taught him at the AA, later observed: “The great thing about Nick was that he wasn’t just in the swim of avant-garde ideas – he actually did them.”

From 1965 to 1980 he worked with Terry Farrell as the Farrell/Grimshaw Partnership. Park Road Apartments, completed in 1970, took an office floorplate and central core approach and applied it to housing, leaving large open floors which residents could fit out as they wanted.

It was developed by a resident-owned mutual of about 40 households, and was one of the first co-housing schemes in London. Grimshaw lived there with his young family for six years.

The Herman Miller factory in Bath, completed in 1976, belongs to a more austere phase of Grimshaw’s career, before the later turn to larger public and infrastructure commissions. It was a stripped-back exercise in flexibility: a 6,000sq m building held up by just two rows of columns on a wide grid.

The cladding system of fibreglass and glazing was designed to be fully demountable, so that panels could be swapped around as production needs shifted. Energy performance was carefully considered too, with the proportions and insulation helping to reduce running costs.

Flexibility is often cited as a central tenet of high tech, though in many cases it has proved more rhetorical than real. The Herman Miller factory showed how the idea could be delivered in practice.

More than four decades after its completion, the building was reworked by the practice into Bath Spa University’s Locksbrook Campus, completed in 2020. The conversion preserved the original structure and modular façade while accommodating a completely different programme of studios, workshops and social spaces.

The split between Farrell and Grimshaw, believed to have been acrimonious, sent the two architects in very different directions. Grimshaw became a central figure, with Rogers, Foster and Michael and Patty Hopkins, in high tech. Farrell became better known for postmodernism and his interest in urbanism.

In 1981, the newly formed Nicholas Grimshaw & Partners delivered one of its first major commissions with the Vitra factory at Weil am Rhein in Germany. The project had to be completed at speed following a devastating fire, with new facilities delivered in just six months.

Using precast frames and lightweight cladding, the building combined rapid construction with the clarity and adaptability that had become hallmarks of Grimshaw’s work. It was also the first element in what would grow into the celebrated Vitra Campus.

By the late 1980s, Nicholas Grimshaw & Partners had hit its stride. The Financial Times Printworks in London’s Docklands, completed in 1988 and now grade II* listed, was a bold expression of high tech’s fascination with process and transparency.

Its long, glazed façade made the presses visible from the outside, turning the mechanics of newspaper production into part of the architecture. Behind the façade, a stripped-back hall was organised around a clear central spine, designed to adapt as printing technology evolved.

In Camden, the Sainsbury’s supermarket and canal-side houses of Grand Union Walk, both completed in 1988, took a kit-of-parts approach into retail and housing.

The supermarket’s structure made a large, clear span feel effortless, its shallow roof trusses and exposed steelwork opening up the shop floor. Its frontage on Camden Road is not exactly contextual, but neither does it feel aggressively indifferent to where it is.

The houses made ingenious use of a thin strip of land beside the canal, with top-lit living rooms and balconies overlooking the water. Built in tough blockwork with precast floors, they nonetheless felt light-hearted and optimistic, an inventive answer to a difficult site.

Waterloo International, London’s original Eurostar terminal, completed in 1993, turned what by then felt like a confident architectural language into public theatre. The long, curving roof responded to train geometry and site constraints, threading a new international terminal into a tight city block.

The project won the RIBA Building of the Year and the Mies award. More than prizes, it seemed to catch a mood.

The waiting areas under the platforms had a retro-futurist feel and the direct trains to Paris and Brussels seemed to reflect a tentative new, confident European air in Britain. It was a vision of London that felt open and self-assured.

The same year brought a new headquarters for the Western Morning News in Plymouth, a glazed, boat-like printworks and office. It now reads like a time capsule of regional newspaper power, a little melancholy in today’s media economy. It did at least prove adaptable, now housing the UK’s largest trampoline park alongside a Clip ’n Climb activity centre.

After Waterloo, the practice became particularly noted for its work in the transport sector, with countless later projects such as Pulkovo Airport in St Petersburg demonstrating its ability to marry structural clarity with the complex demands of major infrastructure. These commissions cemented its reputation internationally.

Expo 92 in Seville was another 1990s high point. A white, tubular frame with pin joints, a kinetic water wall and careful climate response combined to create a lightweight structure that could be assembled, dismantled and re-used.

Then came the Eden Project in Cornwall. Originally conceived as a single, sinuous building tracing the quarry’s edge, the design evolved into a cluster of vast geodesic biomes – an unmistakable nod to Buckminster Fuller. The project captured the public imagination and proved a defining moment, propelling the practice into prominence as one of the UK’s foremost architectural names.

When asked to select a key inspiration for BD’s 50 Wonders series, Grimshaw chose Walter Gropius’s Bauhaus. Visiting it, he wrote, left “an indelible impression of what the modern movement was all about: unscripted space, sparseness, austerity, discipline, daylight, and structural integrity”. The choice underlines how modernism remained central to his practice.

Yet, even at its most accomplished, high tech carried certain tensions. For all its virtues, it could risk becoming a cul-de-sac, with the fascination for technology and kit turning into an end in itself. The city beyond the site line could sometimes feel distant.

The Victorians knew how to dress engineering for the street, borrowing classical and gothic languages to give massive infrastructure projects a civic face. High tech often preferred to simply expose the naked structure.

Perhaps this is why Grimshaw’s buildings can sometimes feel as if they exist in splendid isolation – remarkable objects in themselves, but less engaged in the urban dialogues that a younger generation of architects would seek out, exploring architecture’s role in conversation with its neighbours and the wider city.

Grimshaw today is larger and more dispersed than the studio its founder once imagined. As Mark Middleton, global managing partner, told me in 2022: “This isn’t Nick’s vision. Nick always wanted to keep it small.”

“But,” he added, “we kept Nick’s values and ethos, packed them in a suitcase and took them around the world.” That shift is visible in the firm’s global network of offices and hundreds of staff, and in a leadership model that now spans multiple cities.

Nicholas Grimshaw helped to put British high tech – and British architecture more broadly – on the world stage, building a practice that went on to export that expertise globally. He held fast to the belief that buildings should be reusable and robust.

Accepting the Royal Gold Medal in 2019, he said that he had “always felt we should use the technology of the age we live in for the improvement of mankind”.

High tech may have had its limits, but his work showed how, at its best, it could embody optimism and a belief in the power of technology and innovation to address pressing challenges. It is an outlook no longer universally shared, yet one which defined a pivotal moment in British architecture.

1 Readers' comment