Masterplanning and urban design are frequently conflated but serve very different roles, says Jonathan Tarbatt at Corstorphine & Wright. It is important that we clarify the language, challenge lazy assumptions and advocate for a more rigorous, place focused approach to large-scale development

The terms “urban design” and “masterplanning” are often used interchangeably, but are they really the same thing? Getting introduced as C&W’s “head of masterplanning” does make my heart swell with pride, but my official title is “director of urban design”. Why not use that title instead?

Perhaps because “urban design” sounds vague, even pretentious, while “masterplanning” feels more tangible: a safer term for clients seeking a masterplan. But is distinguishing between these terms useful, or just pedantic?

Confusion arises because, while masterplanning is assumed to be widely understood, it means very different things to different people, especially architects. For some, it is “big architecture”; for others, it is any plan involving one or more buildings, or even abstract diagrams of blobs and arrows.

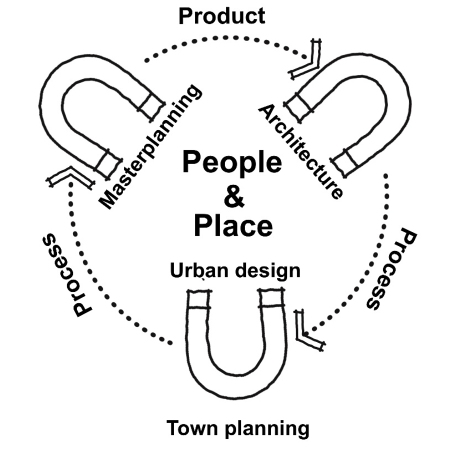

The issue? Masterplanning, architecture and urban design are not synonymous. They are not even siblings – more like cousins.

If you are wondering whether the MHCLG’s newly published Design and Placemaking PPG (consultation draft, January 2026) offers any clarity, sadly it does not. It defines a masterplan as a “placemaking tool” providing a “spatial framework” for development.

The example of a masterplan provided, however, does not include any actual buildings, and captions the masterplan illustrations interchangeably as”spatial diagrams” and as “development frameworks’. It goes on to limit the remit of architecture to the look and functionality of buildings, and that of urban design to the spaces between buildings: both are simplistic assertions.

The term itself has its roots in Old English (maegester) and Latin (planus), denoting “control” and “plan making” respectively

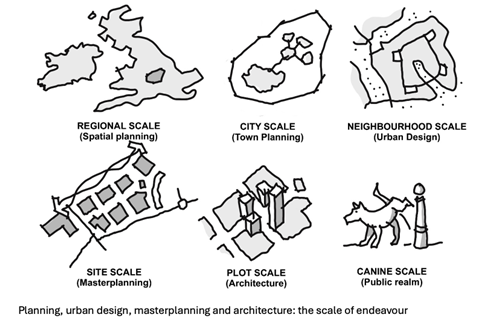

While masterplanning does infer the comprehensive design of large-scale developments, it is more helpful to suggest that it is focused on the interrelationship of different buildings in terms of their urban form, land uses, infrastructure and shared spaces. The term itself has its roots in Old English (maegester) and Latin (planus), denoting “control” and “plan making” respectively.

Urban design, on the other hand, is broader in its scope (and usually wider in its scale too), but crucially, it is also more process related than product or plan oriented, because it has more to do with shaping places as a whole, and improving people’s quality of life, than it has to do with designing developments for a specific purpose.

As David Rudlin suggests in his Building Design piece Master plans are for Bond villains, the term “masterplanning” itself is under increasing scrutiny for its gendered and historical connotations. In North America, it has been criticised for its association with slavery.

Urban designers increasingly prefer the term “urban design framework”, which suggests a flexible set of parameters for development rather than a rigid prescription for what the place will be like when it is finished. But “urban design framework” is a mouthful, and doesn’t necessarily involve designing buildings, which is what architects are all about.

So, are we stuck with a term that is prone to misunderstanding, not fit for purpose, and likely to be cancelled anyway?

The better news, is that the intersection between the disciplines of architecture (plot scale) and urban design (neighbourhood or town scale) is the activity of masterplanning (site scale). Good architects approach masterplanning in the same way as good urban designers do: distilling the wider and local context as the starting point, and amplifying it in a meaningful way, making places that knit into the existing urban tissue, respect heritage and bring life to streets and public spaces in a sustainable manner.

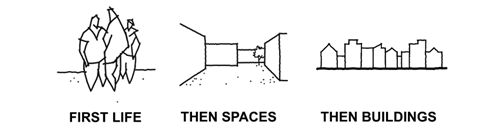

Paraphrasing urban designer Jan Gehl: prioritising the space between the buildings, as the theatre of public life.

“…the other way around never works.” (Jan Gehl)

Architects are already empowered to view the city through an urban designer’s lens, and can approach their masterplanning projects accordingly, in a rigorous yet sensitive manner that mediates between the client’s relatively narrow metric of success, and what “a good place” really looks like.

What architects bring – and urban designers sometimes lack – is a deeper understanding of building typologies, what makes them work in an increasingly complex regulatory environment, and how they can be configured to bring a loose urban design framework to life and to make it deliverable. Otherwise, what’s the point. Right?

Postscript

Jonathan Tarbatt is director of urban design at Corstorphine & Wright

2 Readers' comments