A three-year study into living in some of London’s more recent high-density developments makes fascinating and important reading, writes Julia Park

Living in a denser London: How residents see their homes, a report by Fanny Blanc, Kath Scanlon and Tim White for LSE London and LSE Cities, is one of the many things that risk being overlooked as covid-19 continues to dominate our lives. The research was conducted between 2016 and 2019, and the report published in March this year.

Prompted by the realisation that “Londoners are in the midst of a city-wide experiment in built form”, it makes fascinating reading. Touching on history, politics, policy, affordability, land value, housing need and more, the main aim was simply to understand what it is like to live at high density.

The 14 selected schemes cover a range of tenures and typologies: 11 built in the preceding two to 10 years, and three historic ones for comparison. Architectural quality was not a factor, but the team decided to limit the sample to developments with at least 250 homes and a density of at least 100 dwellings per hectare (dph). It is a very low threshold by today’s standards; indicative perhaps of how quickly things have moved on in the past decade.

The range is huge, though: Strata SE1, a 43-storey tower providing over 400 flats in Southwark, has an eye-watering density of 1,295dph. The number of homes in each development also varies widely, from 268 in Pembury Close (202dph) to 2,818 in East Village (147dph).

Using a range of research techniques including an online survey, focus groups and site visits, the team set out to answer five questions:

- Who lives in these homes?

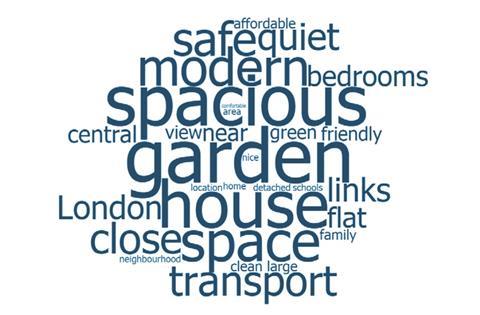

- How did residents come to live in these schemes, and why did they choose them?

- What is day-to-day life like, and what are the pros and cons of high-density living?

- Do residents feel a sense of community in their developments and a sense of belonging to the surrounding neighbourhoods?

- What are residents’ housing aspirations? Do they consider their flats to be long-term homes?

They received 517 survey responses – and the extremely low response rate of 8% is interesting in itself. In the new schemes, 78% of respondents were living in one- or two-person households (compared with 61% in London as a whole) and most were under 40, notably younger than the residents in the older developments. Across the whole sample, annual income ranged markedly, from less than £10,000 (8%) to over £150,000 (6%).

The researchers note that “the physical proximity engendered by high-density built-form did little in itself to encourage community”. Many of the younger, childless residents in the newer schemes were very clear that they had no interest in being part of a community where they live, and that their social networks were elsewhere, in some cases in other countries. Good transport links were seen as a higher priority.

Reading this rather disappointing finding was one of the many times I caught myself wondering whether lockdown might have changed things – and if so, for how long. The households with children were positive about where they lived, but insufficient storage and lack of play space were commonly cited drawbacks. Covid-19 probably won’t have helped there either.

It is the interaction between density, design, location and people that creates a sense of place, and the greater the density, the more important it is to get the other factors right

While a mix of uses appears to increase the sense of community, it often takes time to establish; retail spaces are not always quick to let, for example. Tenure and length of stay seem to be the main factors, as tenants of social housing and owner-occupiers generally stay much longer than private renters, building up enough critical mass to foster a community spirit. Looking ahead, longer tenancies and ending no-fault eviction may help with that.

In itself, the density of a development was not a predictor of success in terms of resident satisfaction. The authors found that “it is the interaction between density, design, location and people that creates a sense of place, and the greater the density, the more important it is to get the other factors right”.

Wise words and timely. National and local policy now overtly support densification. The draft London Plan dispenses with the density matrix, putting the onus on the applicant to demonstrate that their proposal satisfies the policies set out in its 500+ pages. It is a big ask of everyone involved, not least the planners, who have to decide whether to grant permission.

>> Also read: The PM’s ‘build build build’ mantra is out of step with the public mood

Service charges and management also feature in the report (and the draft London Plan). Residents generally felt their blocks were well-managed but wanted a direct connection to those responsible.

In the schemes that had one, the concierge was highly valued. This is not really surprising given that very few of the private renters will meet the people who own the homes they live in. Most are investor landlords and many from overseas, including the Far East where buying off plan, often in bulk, is common.

The report analyses the responses scheme by scheme and ends with a set of lessons that can be learned from the findings. They include:

- High turnover creates challenges for community-building in schemes dominated by private renting, especially when there are many individual investor landlords.

- New schemes can bring sudden sharp increases in local population. Necessary improvements in infrastructure and services should arrive with the new residents, not years later.

- Think creatively about how to provide enough storage for families; either within flats themselves or elsewhere - possibly by repurposing unused parking areas or offering basement storage units.

- Design homes whose spaces can be easily reconfigured as households’ needs change.

- Having accountable on-site staff improves the liveability of new schemes.

- In many cases, it may be better to open amenities to the wider public rather than reserving term for residents only.

- Post-occupancy evaluations should become standard for all major schemes with the findings used to improve existing and future developments. Residents should be involved in these evaluations.

It is difficult to do justice to the report in 1,000 words. Do read it.

Postscript

Julia Park is Building Design’s housing columnist and head of housing research at Levitt Bernstein

3 Readers' comments