With care homes in the news for tragic reasons it is time to imagine a different future, says Julia Park

Care homes are a relatively recent phenomenon and their short history goes some way to explaining why they are still generally seen as “places of last resort”.

Before 1914, those who needed care, and could afford to pay for it, were looked after at home. Those who couldn’t were sent to the local workhouse. These institutions were introduced under the New Poor Law of 1834 in response to mass unemployment caused by the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the industrial revolution, which forced agricultural labourers off the land and into the new factories in the cities but still left thousands without work.

Many were impressive buildings and the healthcare was free, but the conditions were harsh, partly to act as deterrent. The more rural workhouses soon only housed “the incapable, elderly and sick”, and in 1905 a Royal Commission decided they were no longer serving their initial purpose. Eventually local authorities were granted the power to take over workhouses and run them as municipal hospitals or care homes for “the elderly”.

By 1960, just over 50% of local authority-run care homes were former workhouses. Twenty years later, under Margaret Thatcher and Keith Joseph, care provision for older people shifted to the private sector. By 2000, 85% of care homes were privately run. There are now 21,653 care homes in the UK and they each provide 20 beds on average – both figures are less than I expected. The average annual cost to residents is just under £34,000 (much higher in the south east, and lower in the north east) and local authorities only fund the care costs of those whose savings and assets don’t exceed £23,350.

Care Quality Commission (CQC) inspections suggest that the quality of care still varies, but care homes are vital in a society which has moved away from older people being looked after by family members. The many types of specialised housing now available delay, or even obviate, the need for many older people to move to care homes (which, confusingly, don’t offer “homes” in the way that extra care housing does). But for those with the highest levels of need it is often the only viable option.

Care homes are in the press for all the wrong reasons at the moment. Recent ONS figures suggest that a third of covid-19 deaths in the UK have occurred in care homes, but many suggest it could be more. The fact that older people are far more susceptible to covid (as they are to flu) and that administering care inevitably involves close physical contact, accounts for much of the high mortality rate in this sector. But it’s likely that the buildings also play a part.

The care homes built during the 1980s and 90s were generally uninspiring. Their hotel-type layouts were designed for efficiency: their corridors often quite narrow and dark, and the rooms fairly small (the minimum standard is still only 12sq m). They worked better for the staff than for the residents. The theory has been that most people will spend the majority of the day in the communal lounge socialising. Many do – some thrive on the company and activities – but others remain isolated in their room, sad to have had to give up their home and most of their possessions, frustrated that meals and baths happen at set times and that their carers change so often, and counting the days until the next visit from family or friends.

Covid has meant that even the most sociable residents have had to self-isolate. Facing every day alone, apart from the occasional appearance of a masked carer, must be terrifying for those living with dementia. Pandemics are rare events and it would be naïve to suggest that we start designing care homes in the style of a hospital ITU suite, but over the last 10 years the design of care homes has started to improve in ways that make them more homely, more healthy and more resilient, and offer pointers for the future.

Gradmann Haus in Stuttgart featured in the first HAPPI report. It was recognised then as a test bed for research into the role of the living environment in improving the wellbeing of people living with advanced dementia. It left a lasting impression; its 48 ground-floor bedrooms are arranged in two loops of 24, connected by a bright, single-sided “street”. Each loop is lined by a corridor that wraps around a safe courtyard with seating, planting, wheelbarrows, watering cans and other familiar items. Each also has a central café-style cooking and dining space where residents spend most of their time and are encouraged to help with meal preparation.

On the day we visited, the outdoor shade temperature reached 35o but ground-source heat pumps, external shading devices and masses of natural ventilation kept it beautifully cool. The other element that set it apart from any care home I had seen before (or since) were the 18 independent apartments which are available to the partners of the residents, for a modest rent. It allows couples to see as much of each other as they wish, free of “the carer” and “the cared-for” labels that inevitably distort the underlying relationship.

Would it have prevented covid taking hold? Probably not (though Germany has been pretty good at testing and containment…), but it’s hard to imagine a healthier indoor environment for this building type. And the independent apartments would make self-isolation possible while allowing safe contact between couples to be maintained. Having two loops, rather than one, makes it less institutional, and feels more flexible and easier in terms of containment.

>> Also read: Why it’s in all our interests to reinvent the almshouse after 1,000 years

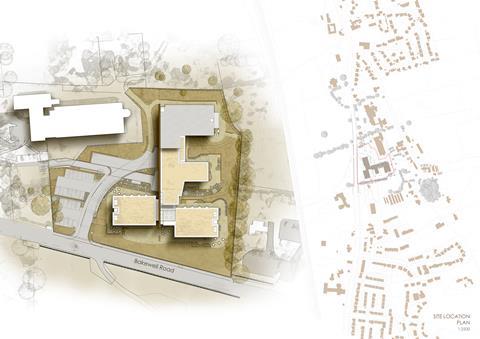

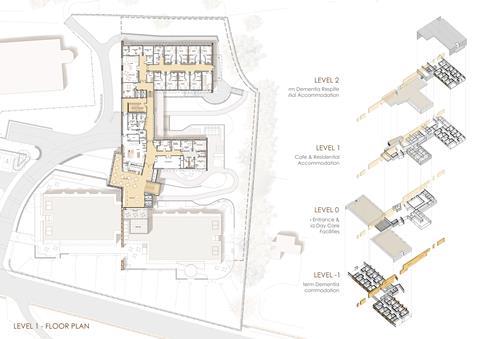

The other care home that springs to mind is Meadow View in Darley Dale, Derbyshire – a more recent specialist residential care facility and community care centre, commissioned and run by the local authority. It too is intended for people living with advanced dementia and is relatively small. Some of the 32 ensuite bedrooms offer long-term care and the others are for people leaving hospital and/or for respite care. Beautifully designed by Glancy Nicholls Architects, you could easily mistake it for a spa hotel. Again, that doesn’t make it covid-proof, but the knowledge that there are places like this (and run by the public sector) makes the prospect of living with dementia a bit less frightening.

The funding and delivery of social care is surely top of the growing list of things that must change when the pandemic subsides. The future design of care homes earns a place on the list, too.

Postscript

Julia Park is head of housing research at Levitt Bernstein and Building Design’s housing columnist

No comments yet