Finalist for Net Zero Architect of the Year Award 2023, van Heyningen and Haward Architects guides us through the specification challenges present at Leicester Cathedral

The judges for this year’s AYAs were impressed with van Heyningen and Haward Architects’ (vHH) body of work, as the practice was named a finalist for two awards including Net Zero Architect of the Year (in partnership with UKGBC).

In this series, we take a look at one of the team’s entry projects and ask the firm’s partner, Josh McCosh, to break down some of the biggest specification challenges that needed to be overcome.

What were the biggest specification challenges on the project?

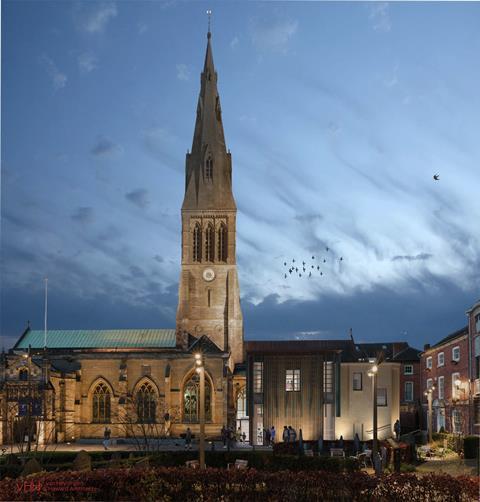

The Leicester Cathedral Revealed project has two very different components: reordering the historic cathedral, refurbishing its fabric and replacing its building services; and creating a small extension.

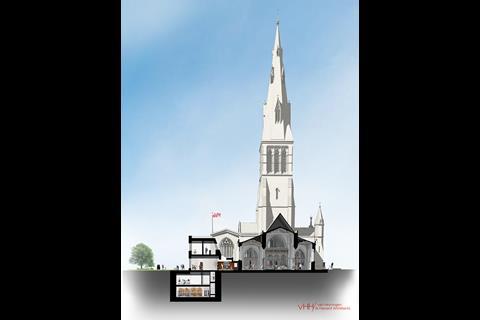

The extension to the cathedral provides all the facilities needed but which cannot be provided in the historic building: storage, toilets, baby change, volunteers’ and vergers’ room, orientation gallery, and education base. The building replaces a 1930s vestry block on a very small footprint, so the space is created by building up and down, with two below-ground levels. One might think of it as a small, functional iceberg.

The biggest challenge was finding ways to gain consent from the Cathedrals Fabric Commission for England (the Church of England’s statutory authority) and the local planning authority. As one might imagine, they did not agree much. The judicious specification was fundamental to this, with much debate, leading eventually to the granting of our consent.

What were the key requirements of the client’s brief? How did you meet these both through design and specification?

The brief sought transformative change: making the cathedral appropriate for contemporary worship, hosting a wide range of public and civic events, and providing a warm welcome to all its many visitors. The project follows on from our 2008 masterplan and our subsequent project to reinter Richard III and the reordering of the chancel and creation of his tomb – and sets out to reorder the rest of the cathedral.

The first challenge was due to the nature of the building, a grade II-listed medieval church much rebuilt in the 19th Century and elevated to cathedral status in the 1920s. With the Richard III work, we succeeded in relocating the main altar, but the building was otherwise no longer fit for purpose: a single acoustic environment, no storage, no public toilets, and no other facilities. The lighting was dismal, and other building services desperately needed replacement.

We needed to adapt the floor to provide un-stepped access to the eastern parts of the building. We used this opportunity to make it do as much as possible: it carries all the services infrastructure, provides efficient heating, and its gentle incline overcomes the changes in level. Specifying a pale limestone-patterned finish subtly draws one’s view eastward, unifies the congregational space, increases the amount of daylight, and is robust and attractive.

All the specified materials are considered so that they are technically appropriate for the historic fabric and avoid causing long-term risks to it. The stone floor is laid on a limecrete substructure that reduces the moisture-vapour load on the existing fabric. Alterations to panelling are in oak. Lime plasters and lime-based paint are used to redecorate the walls, and the specification endeavours to be ‘like-for-like’.

The second part of the challenge was very different, although it overlapped with the first. The shape of our new building was constrained by its site and the cathedral windows, so the major issue was providing adequate insulation and airtightness in a very complex building form. In the face of strong opposition to creating a certified Passivhaus by the Cathedrals Fabric Commission for England (CFCE), we were ultimately asked to design to as close to the Passivhaus standard as we could get permission for, within the budget.

Below ground, this led to intense three-way design coordination between vHH, Price and Myers (structural engineers), and Etude (Passivhaus consultants) to create a two-storey basement very close to the cathedral’s 600mm deep medieval footings – and still achieve the waterproofing, continuous insulation, and airtightness criteria.

Above ground, all the interfaces and facade materials were constrained by the need for the building to relate well to the historic fabric both technically and aesthetically. This led to the specification of stone walling, with copper and lead roofs, like the cathedral, but in a clearly contemporary manner. Nevertheless, these facades and roofs have Passivhaus levels of insulation and an air barrier designed to achieve < 1.0 m3/m2/h at 50 Pascals (Pa).

All the specified materials are considered so that they are technically appropriate for the historic fabric and avoid causing long-term risks to it

What did you think was the biggest success on the project?

The first section of the project is complete, and the new extension is due to be completed in late summer 2024. Without yet having the benefit of feedback, we are most pleased by the new floor and how it has enabled us to resolve multiple challenges while improving the whole feeling of the cathedral.

It has allowed the removal of generations of cables and the ‘temporary’ ramps from the interior, allowing everyone to move seamlessly throughout the space and gently directing one eastward as one comes in. The beautiful Purbeck, Ancaster and Hopton Wood limestones within the floor pattern enliven the space and reveal the fleeting colours of the cathedral’s wonderful 19th and 20th-century stained glass as the sun moves.

We hope that the new extension will be truly transformative in the life of the cathedral, allowing a much higher standard of operation and enhancing its welcome and outreach. Its quality will help minimise operational emissions, and we hope it will also persuade the various statutory bodies that using the Passivhaus methodology is not at odds with the curtilage of a listed building.

What are the three biggest specification considerations on the project type? How did these specifically apply to your project?

The project is a composite of a low-energy building using the Passivhaus methodology, and a heritage retrofit project.

Passivhaus is construction-agnostic, in that any strategy is permissible so long as the airtightness and insulation values are achieved and the plant, windows and other critical components are good enough.

The performance of the materials and techniques is critical for heritage retrofit, as this mitigates moisture-related risks to the historic fabric and preserves the building for the future.

Within the historic cathedral and for alterations to its fabric, the techniques and materials chosen are specified so that they do not damage what is there. They are generally versions of the existing materials and the detailing seeks to minimise risks and keep the construction moisture vapour-open.

In the extension, the need to meet Passivhaus performance levels led to intense scrutiny of materials and components, so that we could select those that performed suitably, were compatible with the behaviours of the old fabric, and the significance of the building and its heritage setting.

For both reasons, the main consideration for the specifications was the appropriateness of the components and materials to their particular situation. These judgements, encompassing the pre-app discussions that resulted with CFCE and the LPA, were amongst the most challenging aspects of the project.

The Cathedrals Fabric Commission for England provided the following comment:

”The Cathedrals Fabric Commission for England is wholly supportive of the aim of Leicester and other cathedrals to improve their energy efficiency with the aim of meeting the target set by the General Synod of being net-zero carbon by 2030. We are working continually with cathedrals across the country to support the design of interventions that are sensitive to the architectural, artistic, historic and archaeological significance of their buildings, and have already approved many such proposals. In this instance, the Commission was never opposed to Passivhaus per se: it merely doubted that the required airtightness and insulation values could be achieved in a building that would have a wide connection to a large medieval church and was concerned that some of the measures proposed to reduce airflow between the spaces, towards this goal, could have a detrimental impact on historic wood and glass. Consequently, the Commission was unwilling to accept the aim of achieving this standard as a justification for an (earlier) exterior design for the proposed extension that we and others judged would not be a fitting addition to the grade II-listed Leicester Cathedral. The Commission approved a modified proposal that addressed these concerns.”

Project details

Architect van Heyningen and Haward Architects

Our “What made this project” series highlights the outstanding work of our Architect of the Year finalists. To keep up-to-date with all the latest from the Architect of the Year Awards visit here.

Downloads

Architect's drawings

PDF, Size 3.25 mb

Postscript

The Net Zero Architect of the Year Award at the Architect of the Year Awards 2023 was in partnership with UKGBC

No comments yet