Architect has created greenest mosque in Europe after winning competition in 2007

Marks Barfield Architects has completed Cambridge New Mosque, the city’s first purpose-built Islamic place of worship.

The practice won a limited international competition in 2007 to land the project which turned out to be one of practice co-founder David Marks’ last. He died in 2017 aged 64.

Marks was the driving force behind the design concept, saying: “We didn’t want to create a replica or pastiche of something that existed elsewhere. The opportunity to do something English, British, excited us. Now that there is a significant Muslim community it’s time to work out what it means to have an English mosque.”

An entirely timber structure is used as part of an ambitious conceptual strategy that seeks to answer that core question.

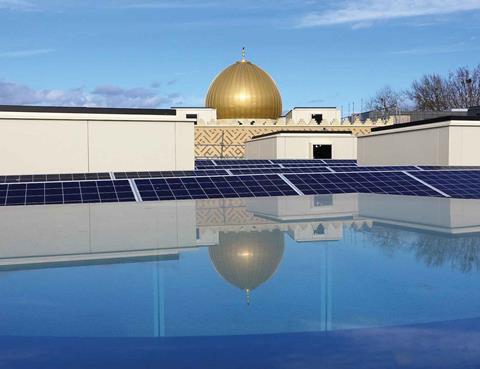

It also allows the building to be described as the “greenest mosque in Europe”. The timber, along with a number of other sustainability features such as a ground-source heat pump and natural ventilation, makes the project close to zero-carbon.

>> Also read: Technical Study: the Cambridge Mosque

Marks Barfield had undertaken one previous foray into Islamic culture with its unbuilt proposals for the Islamia primary school in Kilburn, north-west London, but had never designed a mosque. The client for that school, Yusuf Islam – formerly known as the singer Cat Stevens – is one of the co-clients for the Cambridge mosque, the other being Tim Winter, renowned lecturer in Islamic Studies at Cambridge university.

Julia Barfield, Marks’ partner in life and work, said: “In many ways we approached it as we would any project: we undertook a huge amount of research in order to educate ourselves and ensure that our response was grounded by an understanding of the typology.

“We looked at scores of mosques around the world and discovered that, historically, they were incredibly receptive to local culture, materials and technology and they would adapt to their environment accordingly. For instance, here in Britain we may associate mosques with minarets. But minarets were specifically designed as visual and audial calls to prayer in bustling medieval centres. Surrounded by some of the world’s most advanced 21st-century technology here in Cambridge, you don’t need a minaret when an app can do the same thing.”

Eventually the research unearthed a conceptual starting point: the Garden of Paradise, a longstanding Islamic tradition in which nature is pictured as an oasis that aspires towards an ultimate state of tranquillity and calm. Accordingly, the building itself was to be expressed as a “grove of trees” surrounded by pockets of greenery offering trees, fountains and shelter.

The mosque is a long, mainly single-storey building that occupies a rectangular site on Cambridge’s busy Mill Road. It is separated into a number of segments that, rather like the processional configuration of a nave in a cathedral, are designed to enable the visitor to move sequentially from the entrance through to the holiest part of the building.

First comes a lawned area, described as a community garden, which directly faces on to Mill Road. This leads through to a more formal garden with trees and water features whose symmetry is based on Islamic precedents.

Next the entrance facade is expressed as a deep portico separated by clusters of arched timber piers.

Inside there is a large atrium and cafe area capable of holding up to 300 people, followed by ancillary spaces filled with toilets and wash areas for ablutions.

Finally, the largest and most important space in the building: a vast, 8m-high prayer hall that can hold up to 1,000 people.

It marks a break in the geometry of the rectangular plan because it is slanted to face Mecca. As well as identifying the most sacred part of the building, the kink also helps break down its mass in a manner that is contextually consistent with a primarily residential area.

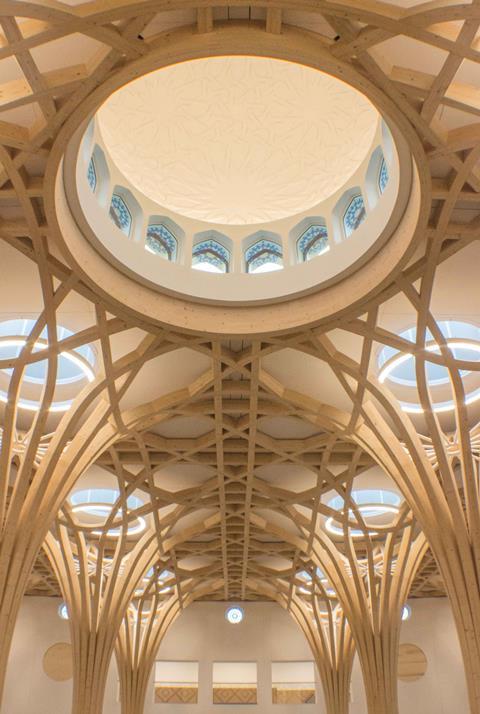

The prayer hall also demonstrates how the “grove of trees” concept has been spectacularly brought to life. Throughout the building the trees are realised as timber piers on an 8.1m grid, creating the building’s defining visual, architectural and structural feature. Each pier comprises a number of timber columns that begin as perpendicular shafts before separating into individual ribs that open outwards like the branches of a tree.

The branches then form an intricate ribbed vault across the ceiling before clustering back down into adjacent piers to repeat the process. Each pier is topped with a glazed oculus that allows light to pour down on to the timber and space below.

The highly complex geometry of the piers and ceiling is based on an intricate Islamic-inspired pattern designed by geometry expert Keith Critchlow, former research director at the Prince’s Foundation and a one-time lecturer of both Marks and Barfield at the Architectural Association.

The octagonal pattern is based on the Breath of the Compassionate, an eight-point geometric star that is revered as a source of beauty within Islam. Here it forms a geometric anchor for all forms of decoration within the building, ranging from floor tiles and ventilation grilles to the piers and vaulting themselves.

While the mosque has no minaret, it does feature a small dome, a late addition to the design, aligned to the mirhab in the prayer hall, an ornamental indention that marks the direction of Mecca.

From the outside, the mosque’s dramatic internal timber structure is visible only through the entrance portico. While it makes a dramatic impact on the street scene at this point, along the rest of the envelope the timber elements are concealed behind an 18th-century brick slip fascia system known as mathematical tiles. The bricks selected are in a buff yellow that is synonymous with Cambridge and, like elements of the interior, are arranged in another Critchlow geometric pattern – this time a rotational symmetry sequence that spells “Allah” in Arabic.

BD’s architecture editor Ike Ijeh said: “The drama of the internal timber structure answers that core question first posed 12 years ago about what a British mosque should be. The most endearing feature of the timber columns is their historic affinity with the fan vaults and lierne vaulting so synonymous with gothic religious architecture, not the least example of which is on display just a short distance away at the spectacular King’s College Chapel.

“Fusing Islamic and Christian architectural traditions in this manner is a symbolic masterstroke that uses the threads of architecture to help bind Islamic culture to the native Christian background of England.”

The country’s first ever purpose-built mosque opened in Woking in 1889, and Barfield’s great-great-grandfather was one of its trustees. For her this coincidence embodies the architectural ambitions of the project.

“For me a 21st-century British mosque is about creating a link between British and Islamic culture, and here we’ve done this by celebrating the universality of nature. This is something unique that links us all, and we believe that this building proves that it’s better to build bridges to connect different cultures than walls.”

5 Readers' comments