Tory grandee says his final report will look at breaking up large sites for delivery by multiple housebuilders

Initial findings from a government-commissioned review into the phenomenon of land-banking in the housing industry have blamed construction giants’ stranglehold over the pace of delivery on large sites as a core problem.

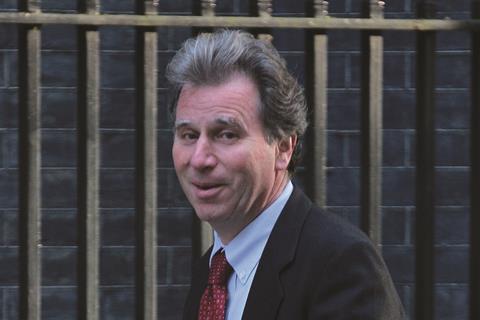

Former Cabinet Office minister Oliver Letwin’s first progress report on the review says developers’ ability to control the release of new homes on particular sites in a way that maintains a desired price – the so-called “absorption rate” – is the key factor in slow delivery.

Letwin also suggests that obligations to fund affordable homes from the proceeds of open-market properties is another slowing factor on build-out, and pledges to investigate alternatives.

He said that the review – which is due to report in full in time for the Autumn Budget – would go on to look at whether breaking up large housing sites for delivery by multiple companies, changing the way affordable housing is delivered, and requiring developers to offer a wider range of homes on sites would increase delivery rates.

Letwin’s appointment to lead a review into the contrast between the number of homes granted planning permission and the number of homes built was announced by chancellor Philip Hammond in November’s Autumn Budget.

The move came more than nine years after an Office of Fair Trading investigation found no evidence of “unnecessary” land-banking in the housing industry, or of anti-competitive pricing among housebuilders, and follows consistent Conservative Party threats for developers to face “use it or lose it” clauses in respect of planning permissions granted for large sites.

While Letwin’s initial findings accepted that skills shortages, “limited supplies of building materials” and land-remediation difficulties all had a role to play, the Tory grandee said he was “not persuaded” that they were the fundamental problem with slow delivery of large sites.

“They are components of the velocity of build-out; but they are not the fundamental rate-setting feature,” he said.

“The fundamental driver of build-out rates once detailed planning permission is granted for large sites appears to be the ‘absorption rate’ – the rate at which newly constructed homes can be sold into (or are believed by the house-builder to be able to be sold successfully into) the local market without materially disturbing the market price.”

Letwin said a further factor was the extent to which absorption rates were influenced by the “fairly homogenous” nature of development on large sites, with prices being affected by targeting broadly the same category of buyer.

He said the next phase of the review would look at the extent to which large sites could potentially be split up between different housing types and tenures so that build-out could be speeded up without impact on prices.

“The principal reason why housebuilders are in a position to exercise control over these key drivers of sales rates appears to be that there are limited opportunities for rivals to enter large sites and compete for customers by offering different types of homes at different price-points and with different tenures,” he said.

Letwin also said his review team had “seen ample evidence” that completion rates for affordable and social-rented homes was constrained by the need for cross-subsidy from open-market housing on site.

“Where the rate of sale of open market housing is limited by a given absorption rate for the character and size of home being sold by the house-builder at or near to the price of comparable second-hand homes in the locality, this limits the house-builder receipts available to provide cross-subsidies,” he said.

“This in turn limits the rate at which the house-builder will build out the ‘affordable’ and ‘social rented’ housing required by the section 106 agreement – at least in the case of large sites where the non-market housing is either mixed in with the open market housing as an act of conscious policy or where the non-market housing is sold to [a] housing association at a price that reflects only construction cost.”

He concluded: “If freed from these supply constraints, the demand for ‘affordable’ homes (including shared ownership) and ‘social rented’ accommodation on large sites would undoubtedly be consistent with a faster rate of build-out.”

RIBA president Ben Derbyshire said the institution welcomed having “some clarity” on the scope on the Letwin review and would be submitting recommendations during its next stage.

Lewis Johnston, parliamentary affairs manager at the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors, said Letwin’s tone was more heartening than the militaristic call for builders to “do their duty” made recently by prime minister Theresa May.

“If the private sector is not delivering the volume of homes needed then ultimately it’s the government’s job to widen participation as a means to find other ways of plugging the gap – we can’t simply implore and rely on volume housebuilders to build more,” he said.

“The only proven way the UK has ever built anywhere near 300,000 new homes a year is when the public sector has been fully enabled as a key delivery agent.

“That’s why RICS has called on the government to fully lift the borrowing restrictions that are currently holding back local authorities.”

Letwin is due to publish full findings in June, which his update said would form the basis for a consultation to inform his recommendations later in the year.

His update letter to chancellor Philip Hammond and housing secretary Sajid Javid can be read here.

3 Readers' comments