This reissued volume on Lutyens’ country houses is a vital resource and spur to further research, writes Jeroen Geurst

When he died, Sir Edwin Lutyens (1869-1944) was the leading architect in the United Kingdom. He had established his fame with the hundred or so country houses he had designed, mainly in Britain and Ireland. From 1912, his fame grew as he was appointed chief architect of New Delhi, the new capital of the then British colony of India, alongside Herbert Baker.

In 1917, when work on Delhi stopped because of World War I, Lutyens was appointed as one of the architects of British monuments and cemeteries in France and Belgium. Although these 130 memorials are his most important works outside the English-speaking world, his name is still known to few in continental Europe.

In the canon of contemporary architectural history Lutyens was an outsider. Lutyens’ image fitted well with the conservative idea of England and not into the development of the modern movement, unlike his peers Frank Lloyd Wright and Charles Rennie Mackintosh. It was not until 1966 that Robert Venturi, with his book Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, that Lutyens began to be brought back to the attention of contemporary architects.

No fewer than 12 works by Lutyens were included in the book as a counterpoint to the uniformity of modernism. The country houses in particular show Lutyens as an idiosyncratic designer who, although a traditional architect, was averse to conventions. His country houses are full of twists in the floor plan and contain an inimitable combination of styles that lead a visitor from one surprise to another, as in a well-staged play.

In 1981, Lutyens was honoured in London with a major retrospective. These were the years of post-modernism, when an interest in Lutyens and tradition had regained a firm foothold in England, partly thanks to Venturi and Denise Scott Brown’s influence. Freely quoting and combining classical motifs in architecture seemed inspired by Lutyens’ work without, however, approaching his spatial quality and materiality.

After post-modernism passed and high-tech and de-constructivist architecture announced itself, interest in Lutyens among architects in England also seemed to fade. Lutyens still has an image as an architect of the establishment, although later in his career he realised an extraordinary social housing project in London.

In addition to his exceptional design talent, Lutyens owed his success in the English-speaking world to the network built up with the help of the landscape architect Gertrude Jekyll (1843-1932). Through his marriage, he also became further acquainted with high-society circles.

Jekyll introduced Lutyens to Edward Hudson, the publisher of Country Life, in 1899. The introduction led to Lutyens being appointed to design Hudson’s residence, Deanery Garden, widely seen as the pinnacle of arts-and-crafts architecture, with a garden by Jekyll.

Hudson published almost all of Lutyens’ work in his lifestyle magazine and had him design the Country Life office and oversee the remodelling of Lindisfarne Castle on the north-east coast of England. From 1910, the two even lived side by side in London and had weekly meals together. Later, Lutyens also designed an extension to the party house, Plumpton Place in East Sussex for Hudson.

The Country Life publications were compiled and published in 1913 in Lawrence Weaver’s Houses and Gardens by E.L. Lutyens, which saw a number of reprints following the 1980s revival.This book ensured that Lutyens became known outside the UK and gained followers. The book included no fewer than 45 country houses that he had already completed halfway through his career. Interestingly, the back of the book included a number of Lutyens’ elaborate design drawings with attention to craft details.

The country houses were mainly for the newly affluent, who combined a busy life in London with a weekend home in the countryside. The presentation of these houses in Country Life had managed to combine the allure of new consumer products, such as the automobile and the hoover on the one hand, with the romance and craft of the country home on the other.

Even before Lutyens’ death in 1944, Lutyens’ son Robert took the initiative to honour his father with a survey of his work. However, the aim was not only to honour his father but also to leave a young generation of architects with a record of Lutyen’s work. The significance of this craft tradition was contrasted with the increasing industrialisation in architecture that was to take place after the war.

The survey borrowed its format from of a series of books on the work of Lutyens’ great inspiration, Sir Christopher Wren. The memorial volumes were published by Country Life in 1950, accompanied by an excellent biography by Christopher Hussey and consisted of three parts.

All three volumes are being reissued by ACC Art Books in handsome new editions. Volume I, which is reviewed here, covers the country houses. Volume II focuses on gardens, Delhi and Washington, and volume III (available from April) addresses the public buildings.

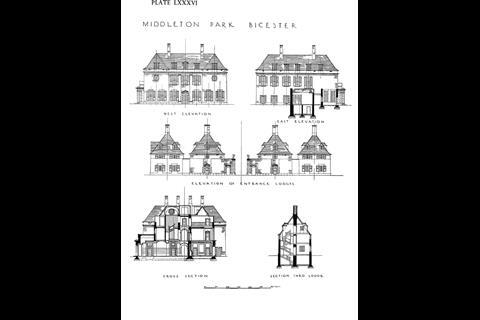

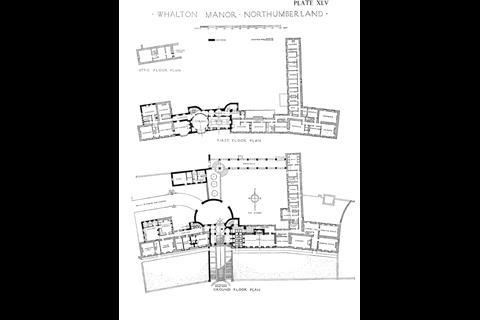

The first volume drew on the excellent Country Life photo archive and includes 25 of the 45 country houses included in Weaver’s earlier book, supplemented by 10 later country houses and 14 small houses. However, the monumental format and layout were different to Weaver’s volume. The text, photographs and floor plans were included in three separate sections, with the design drawings given a central place in the book, many of which had been made after Lutyens’ death by his practice, by then managed by Robert.

In addition to the floor plans, there was the valuable addition of elevations and many detailed drawings of his country houses that showed the craftsmanship of the work well. However, because text, photos and drawings were distributed throughout the book and not by project, it was often difficult to connect the complicated spatiality.

This reissue of volume I has a slightly handier and lighter format than the original and features a more attractive new cover. The white paper makes the drawings appear fresher than in the original. This has made the format slightly more accessible, while the monumental design of the book still strongly exudes the British atmosphere of a century ago.

The complexity of the country houses can only really be experienced by visiting them in situ which, unfortunately, is rarely possible. Lutyens enthusiasts therefore must rely on literature. In that light, the reissue fills an important gap, as only a handful of Lutyens’ country houses can be visited. These can be found on the Lutyens Trust’s website, and include the country houses and residential castles Goddards, Lindisfarne Castle, Lambay Castle, Castle Drogo and soon Munstead Wood, Getrude Jekyll’s own home recently bought by the National Trust.

His only continental European country house is Le Bois des Moutiers in Normandy, which surprisingly was not included in either Weaver’s book or the memorial volumes. It was open to visitors for a long time, but changed hands four years ago and it is not clear if and when it will be reopened to the public.

The publication in 2010 of my book on Lutyens’ World War I British cemeteries rekindled interest in continental Europe in the form of field trips, lectures and a study group of leading architects in the Netherlands. Lutyens’ work continues to prove an inspiration to architects.

This reissue is an indispensable document for further study of Lutyens’ work. And the hope is that it can form the basis for subsequent publications that not only document Lutyens’ work but also analyse, reinterpret and update it.

Contemporary themes appear to be plentiful. Building on history, the reuse and extension of existing buildings and the relationship with landscape are more topical than ever. Lutyens’ emphasis on the experience of the house through an architectural route and his focus on craft both appeal to today’s yearning for domesticity.

Possibly this is a starting point of a new Lutyens revival that can give new meaning to the work. Let it also be an incentive to experience and study his country houses on site, wherever that is possible.

>> Also read: Page Street housing by Edwin Lutyens

Postscript

The Architecture of Sir Edwin Lutyens, Volume 1: Country Houses, by A.S.G. Butler, with George Stewart and Christopher Hussey, is published by ACC Art Books.

Jeroen Geurst is a co-founder of Geurst & Schulze, an architectural practice based in The Hague. He also teaches at the Amsterdam Academy of Architecture. He is the author of numerous publications, including Cemeteries of the Great War by Edwin Lutyens.

No comments yet