Charles Holland enjoys the latest volume in the series on Lutyens’ key works

Few architects have been as lavishly published as Edwin Lutyens. Despite the essentially nostalgic nature of his buildings, Lutyens was a very modern architect when it came to marketing, a canny self-publicist acutely aware of the power of books and magazines in establishing his reputation.

Country Life magazine played an integral role in this, offering a perfect forum for Lutyens’ evocative re-workings of rustic and classical buildings. The magazine’s readers provided Lutyens’ early client base and he was adept at employing architectural imagery that spoke directly to their dreams and aspirations.

The magazine’s beautiful, black and white images of Lutyens’ just-completed projects still remain the best-known representations of his work. In addition, he was personally commissioned three times by the magazine’s owner, Edward Hudson. After Lutyens’ death in 1944, Hudson and his editor Christopher Hussey collected together their archive of photographs along with drawings from his office, and published them in three memorial volumes, edited by the architect and critic ASG Butler.

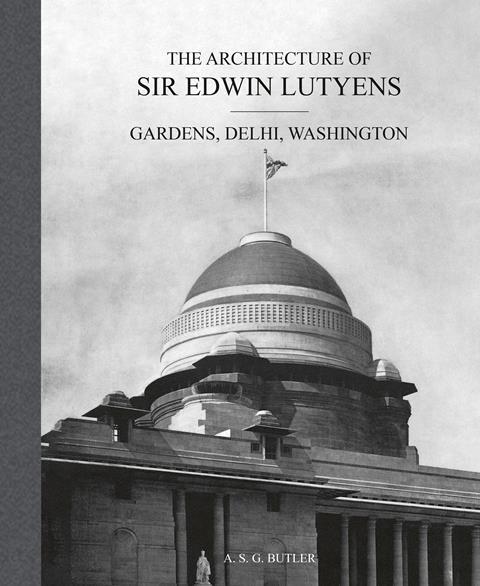

These volumes are now being re-issued by ACC Art Books. Volume 1 (Country Houses) and Volume 2 (Gardens plus New Delhi and Washington) are already available with Volume 3 (Public Buildings) due to be published in April. Together they represent the most comprehensive collection of Lutyens’ work and therefore an opportunity to re-appraise that work today.

The country houses in Volume 1 represent Lutyens’ best known and arguably most admired projects. Here we see his familiar career trajectory from the early reworkings of historic Surrey houses like Crooksbury – completed in 1889 - to the vast, classical compositions of his later years such as Gledstone Hall in Yorkshire, built in 1927. This progression from informal vernacular to formal neo-Georgianism is not entirely linear, however. Lutyens’ work contained hints of classicism from the off and he revisited his more playful, vernacular work in later years. Sometimes he even reversed the sequence.

A good example of this is Folly Farm, originally designed by Lutyens in1905. Here, he took a small, 17th century cottage and added a perfectly symmetrical, h-plan house in his ‘Wrennaisence’ manner: purple bricks, white-painted sash windows and classical proportions. Nothing with Lutyens is entirely what it seems though. The carefully co-ordinated symmetry of Folly Farm was disrupted by a deeply peculiar entrance sequence starting not in the centre of the composition as one might expect, but at one end where the front door was mischievously hidden from view. Once located, the front door led to an elliptical entrance hall which squeezed visitors – like toothpaste from a tube – into an unexpectedly grand hall that took up the entire volume of the house.

Lutyens extended Folly Farm in 1911, this time employing a version of his earlier, neo-vernacular mode. In effect he added a pseudo-medieval barn to a faux-William and Mary-style house which was itself appended to a genuine 17th century farm. None of this can be considered straightforward or even particularly ‘real’ in any clear sense. Instead, what we see is a series of fantasies and illusions conjuring multiple periods and styles, all placed in artistic tension with each other.

Lutyens was not alone in this approach. Many of his contemporaries were happy to combine vernacular exterior forms with classical interiors. The idea of the zeitgeist, or a clear, contemporary style as we might understand it now made little sense to them. Neither did a concept of architectural history as a linear progression from one style to the next. Instead, they were engaged in an exploration of various historical styles often employed in happy contradiction with each other.

Lutyens was simply more extreme and more imaginative at this game than other architects. He also had a firmer grasp of geometry and the formal possibilities of architecture. So, the move towards an ever more severe and disciplined classicism – referred to by Lutyens as ‘the high game’ – was also inevitable. Heathcote in Yorkshire – completed in 1905 – is a particularly flamboyant, relatively early example: an essay in late-Renaissance, Italian mannerism bizarrely at odds with its setting on the outskirts of Ilkley.

Lutyens’ formal predilections are just as evident in his garden layouts featured in Volume 2. Here, he corralled domestic landscapes into elaborate geometric configurations. Circular and semi-circular steps, pools and pergolas predominate, forming the equivalent of external rooms held in tight compositional relationship via axial grids. Lutyens frequently collaborated on these designs with Gertrude Jekyll, a brilliant garden designer whose picturesque planting worked as a foil to the formality of the spatial layouts. Jekyll was also an important early champion: she commissioned Lutyens to design her house at Munstead Wood in 1896 and nurtured his early career. Deanery Gardens in Sonning – completed in 1901 - represents the high point of their collaboration, a brilliant, highly geometric composition that nevertheless abounds in richly sensuous planting.

Volume 2 is dominated though by Lutyens’ work in India on the Government Buildings of New Delhi. This opulent, imperial confection was a collaboration with his contemporary and one-time friend Herbert Baker. It resulted in an irrevocable split between the two when it transpired that Baker had adjusted the site levels in order to diminish the impact of Lutyens’ Viceroy’s Palace, which appears oddly low and almost lost at the end of its imperial vista. This was Lutyens’ version of events at least, and he embarked on a vicious campaign of negative PR against Baker in retaliation.

Nonetheless, the Viceroy’s Palace remains an extraordinary achievement, a fusion of Edwardian pomp, traditional Indian symbolism and Lutyens’ endlessly inventive way with classical forms. Against the Indian sun, Lutyens designed razor-sharp mouldings that project powerful shadows across the façades. The pretty, pink stone, carvings of elephants and the use of small, aedicular-like elements help to offset the scale of the edifice, and the interior abounds in rich spaces and dramatic illusion. Most striking of all perhaps is the central staircase where a huge, curved cornice holds up nothing but the sky.

The third volume of this trilogy will feature many of Lutyens’ institutional buildings including his work for the Midland Bank and the Imperial War Graves commission. These later works continue the invention of his earlier buildings but combined with a monumentalism that would ultimately culminate in his largely-unbuilt plans for Liverpool Cathedral, an epic project sadly abandoned after his death.

Although the principal attraction of these three volumes is the wealth of photographs and the exacting details produced by Lutyens’ office, Butler can be an astute critic. He is not shy of calling Lutyens up short where necessary. Describing Witwood, a relatively small early domestic work, Butler writes of the “disastrous effect” on the internal planning of Lutyens’ striving for symmetry. He is critical of the over-elaboration of many of the gardens and the technical problems that resulted from Lutyens’ inventiveness. He also recognises that Lutyens could be loftily dismissive of his client’s wishes.

When it comes to masterpieces such as Little Thakeham – a classical ruin lurking inside an Elizabethan manor house or Deanery Gardens – an architectural dream world as powerful as Alice through the Looking Glass – Butler writes with generous and lavish praise. Rightly so, because these houses represent an orchestration of space, materials and form that is truly of the highest level. Lutyens was hugely lauded during his lifetime and honoured on his death by this vast compendium of his work. But, as they say, he was worth it.

> Also read: The Architecture of Sir Edwin Lutyens – Volume 1: Country Houses

Postscript

The Architecture of Sir Edwin Lutyens – Volume 2: Gardens, Delhi, Washington, by A.S.G. Butler, with George Stewart and Christopher Hussey, is published by ACC Art Books.

Charles Holland is director of Charles Holland Architects and a professor of architecture at the University for the Creative Arts.

1 Readers' comment