Sarah Simpkin reviews Concéntrico: Urban Innovation Laboratory, a new book celebrating a decade of inventive public-space interventions that have transformed the Spanish city of Logroño into a living laboratory for urban experimentation

What was the last project you saw in the press that really caught your imagination? Not for a tidy bit of joinery, but an idea that stopped you in your tracks for its inventiveness. Maybe one you went so far as to tell people about.

Well, as you ask, for me it was an installation this summer in the Spanish city of Logroño for Concéntrico, the architecture and design festival. Leopold Banchini Architects enclosed an underwhelming fountain on a traffic island with timber walls to create a temporary public bath house.

With simple means, it sheltered an exposed spot on the Gran Vía to allow a new use. And an old one – a reminder that the function of early fountains was to provide water to drink and wash with. It’s interesting to imagine similar potential in London’s roundabouts. Perhaps a bath house for the Marble Arch pools?

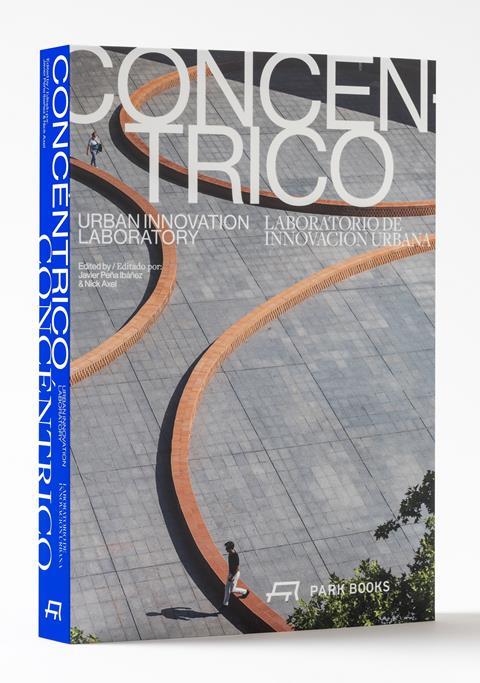

Leopold Banchini’s Round About Baths doesn’t actually appear in the new Concéntrico: Urban Innovation Laboratory (Park Books, 2025), as likely the most recent installations came too late for publication. But there are plenty of other projects to inspire. The book surveys the first decade of the festival, which has transformed Logroño and the surrounding countryside of La Rioja with over 150 public space interventions by local and international artists and designers.

Audience participation

The book’s launch at the Instituto Cervantes opened with some Almodóvar-worthy technical mishaps. Everyone chipped in with their opinions as amateur sound engineers, breaking down any barriers there might have been with the audience, just as these urban installations aim to do. Concéntrico’s founder, Javier Peña Ibáñez, discussed the book with artist and spatial designer, Sahra Hersi.

They examined the local meaning of projects like Willem de Haan’s Public Monument. In 2024, the Dutch artist built a small brick ‘house’ in place of the pedestal of one of the city’s most famous statues. It had the trappings of domesticity; a chimney, net curtains and ‘for sale’ sign in the window, table and chairs on the terrace, but also a bronze horse carrying former Prime Minister, General Espartero, on the roof.

Ibáñez recalled an elderly man crossing the temporary bridge over the fountain’s basin to sit on a stone sphinx and recreate a photo from his childhood, taken before the monument was surrounded by water. “These are the encounters that make the festival,” he said.

Obviously, these kinds of pieces comment on rather than address the housing crisis, which bites in Spain as it does here, worsened by short-term tourist lets, new build deficits and rent increases far outpacing earnings. But in successful, convivial neighbourhoods, life isn’t only lived in the home. Visit almost any Spanish town, village or city in the early evening to be reminded of that.

‘Bored of Biennales’

That same London Design Festival week, appropriately, I went to ‘Bored of Biennales’, a Turncoats debate questioning the value of such festivals. Every criticism levelled at their opaque financing, exclusivity, public irrelevance or carbon cost was fair, but didn’t seem to apply to the projects in Logroño.

Concéntrico doesn’t platform an industry talking to itself; public participants matter as much, probably more, than the media. Its success rests on trust between communities, institutions and local government – relationships built by Ibáñez and greatly helped by having lived in the city.

Someone asked him if he thought it could work in London. “No,” he said, “too big. But maybe at a neighbourhood scale.”

“After ten years,” said Ibáñez, “we are trying to think how we can be more than a festival, because as great as it is, festivals do have certain constraints and restrictions.”

Plans include permanent installations and school programmes. Already, the team has collaborated with a secondary school and architects Recetas Urbanas on a project, Rebellion of the Crazy Army, ‘breaching’ their campus fence with steps, a gangplank and a bright yellow stage to connect it with neighbouring streets.

Some projects in the book are modest. At ESDIR, La Rioja’s school of design, alumni trio Clara Alonso, Marta Basterra and Mikel Aguerrea used the well of a broken lift to create an intimate nook below pavement level for an open-air library and reading room. Elsewhere, artist Benedetto Bufalino reclaimed space taken up by private storage by building a wooden deck over three parked cars.

Others are simple ideas writ large. Puerta Extra-Ordinaria by Associates Architecture completes a section of the old city walls with a dramatic wooden gateway.

In an early edition of the festival, The Centipede by Picado de Blas spanned a church square with a serpentine communal table. It took its name from the fable of the centipede and spider: “the spider asks the centipede how they walk with so many legs and the centipede never walks again.”

The point, I think, is not to overthink instinctive action, and it applies to all these interventions – an obstacle interrupts the routine, forces a negotiation and, in doing so, opens up unexpected routes through familiar ground. This is best expressed by the book’s cover project by Lanza Atelier. Three brick circles alter the flow of people through the plaza at the heart of Rafael Moneo’s Logroño city hall.

The bricks are stacked at seat height, not fixed, so that they can be easily disassembled and reused. The architects liken them to people, as “pieces that meet in an instant and then move away from each other, like citizens at a demonstration.”

A London roundabout bath house?

But back to Leopold Banchini’s Round About Baths. Could we try that here, do you think – a public fountain bath house? It happens in Basel. Visiting this summer, I was surprised to find Swiss fountains bathing actively encouraged, in contrast to the UK, where the water and our relationship with it feels increasingly murky.

I consulted architect and author, Chris Romer-Lee, co-founder of Swimmable Cities, a group that campaigns for access to urban water. “I can’t see it happening soon,” he said. Working with artist, Amy Sharrocks, he once proposed a project called Open Water that aimed to open fountains and hidden swim spots for one day a year.

The idea was shut down by the council over health and safety concerns and, he adds, “perhaps fears it disrespected London’s heritage.” Not a problem in Logroño for General Espartero on his horse on a house.

“Opening up bodies of water for citizens to cool down is going to become increasingly essential. Opening fountains seems a no-brainer. If that still concerns the authorities, let’s make developers build ‘blue’ spaces in our cities, in the same way they are required to do ‘green’ spaces.” Yeah!

Sometimes, our self-imposed Brexile can feel like watching good initiatives in Europe through a window we’ve slammed shut on ourselves. Still, a book like this – and yes, biennales too, at their best – remind us of the value of looking outward.

And at a point when, for some, urban intervention seems to mean painting a roundabout, Concéntrico suggests how simple, imaginative acts could create common ground. We need more centipede tables and brick benches. More space for encounters that can bring us together and start conversations at the scale that matters, the neighbourhood.

Postscript

Concéntrico: Urban Innovation Laboratory is published by Park Books, 2025.

Sarah Simpkin is a writer and communications consultant.

No comments yet