William Butterfield’s designs, from All Saints, Margaret Street to village churches in the Aire Valley, are explored by Nicholas Olsberg in a richly illustrated study. Andy Foster examines how the book broadens our view of an architect admired as much by Brutalists as by his Victorian contemporaries

William Butterfield (1814-1900) was one of the greatest of High Victorian church architects. He’s also been much appreciated by later practising architects: the postwar Brutalists, like Peter and Alison Smithson, made him one of their heroes. He was an unusual, difficult man. He lived alone, had friends but not many, was remote from the assistants in his office. He walked every day to the Athenaeum for a ‘dish of tea’. He took few pupils (but they included Henry Woodyer and Halsey Ricardo). He would have nothing to do with competitions. He refused to take W.R. Lethaby as a pupil because Lethaby mentioned in his interview that he had had something to do with a competition. He wrote boiling reactionary letters to the High Church newspaper, the Guardian, and pasted them into a book. A friend who was allowed to borrow some drawings and kept them a few days too long received an angry letter.

Yet he was a very great architect. His use of constructional polychromy – patterns of red, blue, and cream bricks – is famous and for some off-putting, so perhaps it’s best to start a judgement elsewhere. All Saints Margaret Street, built as a model contemporary church by the Ecclesiological Society, has convincing proportions and plan quite different from mediaeval Gothic: very tall arcades with wide bays, and short chancel, so the congregation can see the priest.

At St. Matthias Stoke Newington, and then Milton in Oxfordshire, he created a powerful church type with a tower over the west part of the chancel, very influential in the later Victorian and Edwardian periods: Norman Shaw’s churches at Leek and Swanscombe, and local architects like W.H. Brierley at Goathland, Yorkshire, and Philip Chatwin at Witton, Birmingham. His chapel at Balliol College, Oxford, had external wall arcading which was an inspiration to George Gilbert Scott junior (“Middle Scott”) and others.

In domestic architecture, his houses at Baldersby in Yorkshire have proportions which could only come from long study of Gothic design, but are so simple that they could almost be misdated by fifty years as Arts and Crafts work of around 1900.

Lethaby divided Gothic revival architects into ‘Softs’ and ‘Hards’. The Softs “turn to imitation, style ‘effects’, paper designs and exhibition”, the Hards were founded on “building, on materials and ways of workmanship, and [proceed] by experiment.” Butterfield was his greatest “Hard”, a “builder-architect”. “His London works are… the most possible buildings erected in the name of revived Gothic … A study of Butterfield’s work would be really instructive.”

There have been several. Compared to his equally great contemporary G.E. Street, he has been well appreciated. Street had only a valuable pamphlet by H.S. Goodhart-Rendel before Geoff Brandwood’s fine but quite short book published posthumously (with much help from Peter Howell) in 2024. Butterfield has a celebrated study by Sir John Summerson of 1945, “William Butterfield or the Glory of Ugliness”; Paul Thompson’s full-length monograph of 1971; and a Victorian Society symposium, “Butterfield Revisited”, of 2017, edited by Peter Howell and Andrew Saint: stalwart fans of Butterfield’s work for many years.

This book is rather different. Nicholas Olsberg went to Rugby school, with its important Butterfield buildings, and became Head of Archives for History of Art at the Getty Center, buying many Butterfield contract drawings in 1985. So this is not a biography, where Thompson’s book is still the standard work. It’s a series of studies of groups of buildings in their social context.

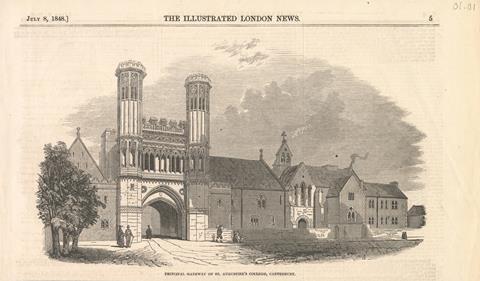

It starts with Butterfield’s first major Anglican commission, St. Augustine’s College in Canterbury, and goes roughly chronologically through his career. This nicely complements Thompson’s approach, which analyses the work – it’s tempting to say, deconstructs it – into its treatment of wall, roof, mass, line. Olsberg emphasises Butterfield’s building approach to architecture. Oddly, though, Lethaby is never mentioned.

There’s plenty about Butterfield’s clients, Tractarian landowners like William Dawnay, 7th Viscount Downe, who rebuilt parish churches and built mission churches in Rutland and Yorkshire; and George Boyle, the 6th Earl of Glasgow, who effectively bankrupted himself building the College of the Holy Spirit on Great Cumbrae; and heroic priests like Edward Penny of Great Mongeham and Charles Holthouse of Hellidon.

After St. Augustine’s, Olsberg turns mainly to schools, cottages and parsonages

Olsberg, perhaps with his schooling in mind, is clearly concerned to broaden the traditional view of Butterfield, as the architect of big urban churches from All Saints, Margaret Street, to St. Augustine’s South Kensington. He starts, rightly, with St. Augustine’s College in Canterbury, Butterfield’s first major religious work, which made his reputation. So we learn about the group of influential Tractarian clergy and laity called the Engagement. Butterfield was recruited into this in the 1840s, and it turned him from a minor young architect into the chosen designer of the Ecclesiological Society and one of the greatest architects of his time.

After St. Augustine’s, Olsberg turns mainly to schools, cottages and parsonages, and Butterfield’s smaller mission and village churches, for which he clearly has a great affection. One of his loveliest descriptions is of the little Oxfordshire church at Horton-cum-Studley (a favourite of mine too, I should say) with its “bright palate of yellow, scarlet, and blue bricks that stands out like a haystack strewn with poppies and cornflowers in the meadows of Otmoor”.

He dwells on the trio of modest but totally original brick mission churches in the dour Aire Valley at East Cowick, Hensall and Pollington, in land “like absolutely nowhere else in its emptiness in the British Isles.” This ordering brings some problems. Olsberg is concerned, correctly, to point out the “unprecedented” design of St. Matthias, Stoke Newington; but its later country cousin at Milton comes first here.

The great buildings are treated at length, some way into the book. There are good descriptions of All Saints Margaret Street and St. Alban Holborn, but again, the ordering means they come after the much later restoration of Ardleigh, Essex.

The account of All Saints begins rightly with “the extraordinary and unexpected effect of the great height of the nave and the groin-vaulted chancel… then the open rhythm of the great nave arcades” – structure comes first – and only then describes Butterfield’s polychrome decoration. Olsberg’s treatment of this can’t be bettered, starting at the font, and stressing the repetition of simple figures which integrate the design and how “Butterfield’s ingrained structuralism works to contain this potential for excess by confining the most exuberant ornament to points at which it can be seen to grow out of the constructive form…”.

This leads naturally, at St. Alban, Holborn, to E.W. Godwin’s criticism of Butterfield as ugly. It is good that Olsberg reminds us that this attack was made on Butterfield by his contemporaries, and not minor ones. Sir John Summerson has been blamed for it frequently. His essay was the first modern re-assessment of Butterfield, not an attack on him.

The other problem is that Olsberg’s kind of detailed social history requires a commanding knowledge of Victorian society, and particularly with Butterfield, the Victorian church. Here anyone can go wrong

Olsberg can slip into hype. There are places quite as empty as the Aire Valley. Alvechurch rectory is a good and significant building, but Olsberg says “To the architectural community it was a revelation.” Was it? It wasn’t, for example, illustrated in The Builder, which drew All Saints Margaret Street, and St. Alban, Holborn.

The stone screen at Great Cumbrae isn’t “a work of complete originality”. It’s a creative re-working, a very fine one, of the Essex screens at Great Bardfield and Stebbing (which was, interestingly, restored by Butterfield’s pupil Henry Woodyer). It has to be said that even Butterfield is not always successful. Exeter Grammar School is a bleak range of buildings which could almost be a barracks, which you won’t realise from Olsberg’s description of “force, harmony and beauty”. He talks of its struggles to maintain numbers, but they were because it supplemented an established grammar school, Hele’s.

He can also get rather close to Pseud’s Corner. His language is lyrical but accurate at Horton-cum-Studley and Margaret Street, but we do get: “Butterfield develops a specific aesthetic grammar for the country school, inscribing into the rural landscape little poems to civility and aspiration.”

And St. Augustine, Queen’s Gate (South Kensington); “Like the masterpieces of Ravenna and the Venice lagoon, the power of the design came from concordance, from the field of animation and not its components. It is inside and out composed of so many incidents so scrupulously resonant of one another and so ingrained in the fabric as a whole that it was effectively without incident at all.”

I think that means that all Butterfield’s original detailing is integrated into, and subservient to, the whole design: the same point well made about Margaret Street. It might have been better to say that.

The other problem is that Olsberg’s kind of detailed social history requires a commanding knowledge of Victorian society, and particularly with Butterfield, the Victorian church. Here anyone can go wrong. John Keble was not inhibited by his bishop (though his curate was refused ordination). Except for a short passage about St. Alban, Holborn, there’s little sense of the background of Tractarianism changing into Anglo-Catholicism, where Butterfield would not follow, though several of his churches did.

Father Mackonochie at St. Alban’s wasn’t attacked because of “Radical and socialist causes” but because of his liturgical practices. “The parade of town halls, insurance offices, banks and law courts” is a confusion of public works, mostly after the later Victorian creation of local authorities, and commercial enterprise. There is no “hegemony of money interests and civic order”. They were distinct, and libraries belong with town halls.

There is so much good here, in describing Butterfield’s building, discussing his clients, and fitting them into their social background

It can be carping, I admit, to list small mistakes, but there are quite a few. Pugin’s convent in Birmingham is anything but “domineering”; it’s modest and domestic. Butterfield did not design the school at Elerch; it’s by G.E. Street (and now sadly turned into a house). Lord Downe’s succession to an Irish peerage didn’t stop him from sitting in the House of Commons. St. Mary de Castro, Dover isn’t “the oldest surviving site of a church in Britain”. It’s a Saxon church attached to a Roman lighthouse. If the phrase means churches still in use, it’s almost certainly St. Martin’s, Canterbury.

The illustrations are a large part of this book, and they are unusual. There are many good reproductions of the contract drawings at Getty. The book is almost worth it for these alone. There are contemporary photographs and, interestingly, several postcards. These are complemented by photographs taken for the book by the celebrated James Morris.

Many are, deliberately, of parts of buildings rather than the whole. They have a very definite style, pale, washed-out, the exteriors under unvarying grey or white skies, with Butterfield’s colouring muted. You feel it has just stopped drizzling, and may start again. A foggy morning is clearly welcome. There is a great view of St. Alban, Holborn, taken from the top of a building to reveal nearly all of the west front. But it’s pale, over-exposed in fact, and with the west front in light shadow. Butterfield, as visitors to Margaret Street and Keble will know, liked his colours bright.

Only the extraordinary decoration above the chancel arch at All Saints, Harrow Weald, where for a moment you think it’s postwar Modernism, is bright here. All Saints, Margaret Street, only has Morris photographs of the exterior. The interiors are just the perspective from The Builder and an early photograph, and one longs for a good modern colour view. As Olsberg says, photography has improved since Thompson’s biography.

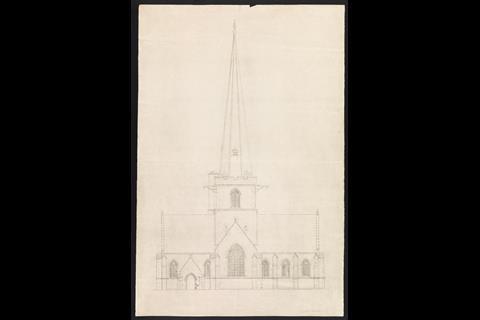

Morris’ approach does work for, say, the mission churches in the Aire Valley. But elsewhere his pictures can miss the point. The early village church at Sessay is a simple aisled nave and chancel, with west tower and spire. It is before Butterfield’s discovery of colour.

Its originality is in the massing, where the nave roof changes to a shallower pitch for the catslide aisle roofs – commonplace later, new then – and the fenestration, where nothing is conventional. The south aisle has a single four-light south window and a circular east window with complex tracery. The chancel has lancet and two-light windows at different levels. It all works, because Butterfield has placed them perfectly in large areas of grey local stone, rather like the carefully placed windows in some Modernist house. But Morris’ moody and atmospheric photographs show nothing of this.

There is so much good here, in describing Butterfield’s building, discussing his clients, and fitting them into their social background, and his original drawings, that it far outweighs the book’s drawbacks, which niggle, but do not damage. It’s a major contribution to Victorian architectural history and if you have any interest in that, it should, along with Thompson’s biography, be on your bookshelf.

Postscript

The Master Builder: William Butterfield and His Times, by Nicholas Olsberg, is published by Lund Humphries.

Andy Foster is an architectural historian and author of the Birmingham Pevsner City Guide and the Pevsner Buildings of England architectural guide to Birmingham and the Black Country.

2 Readers' comments