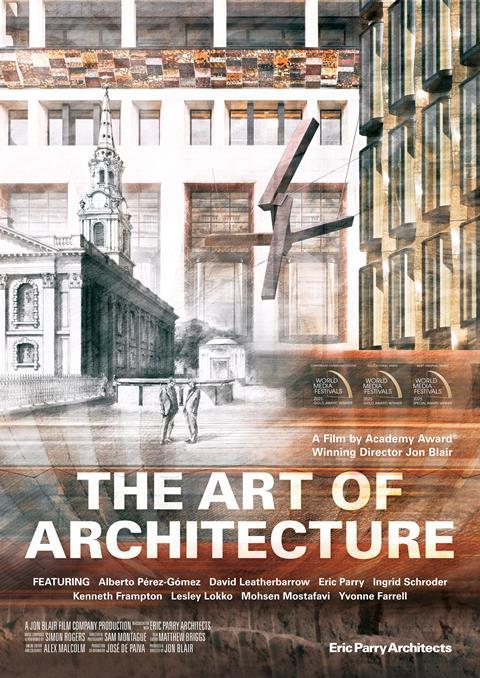

Nicholas de Klerk reflects on The Art of Architecture, a new film by Academy Award-winning director Jon Blair, which explores Eric Parry’s work and provokes questions about how architecture is judged over time

The opening question in Jon Blair’s film about Eric Parry’s practice and work is a broad one, and one which stumped most of the architectural luminaries that he posed it to: ‘What is Architecture?’

I confess that on arriving at the premiere, hosted at BAFTA’s storied premises located on London’s Piccadilly, I had a couple of slightly more focused ones: ‘Why a film about architecture and why now?’

I don’t think I came away from the film with clear answers to either of those questions, but I did gain a few entry points into a wider field of enquiry prompted by the more philosophical concerns that underpin Parry’s work. Blair himself noted that he didn’t know who the film would be for, so decided to make it for himself, going on to say that he thought that asking questions was more important than providing answers.

The question of architects on film, or indeed films about architecture, is a curious one, and a film about the life or work of a living architect is not without precedent. Sydney Pollack’s final film in 2006 took the form of a documentary which considered the life and work of Frank Gehry, and in doing so, interviewed a cast of cultural and architectural figureheads alongside Gehry himself.

Tomas Koolhaas’ 2016 documentary about his father Rem is more intimate, elegiac even, with an unexpected sequence spent considering a life and practice without the architect himself. To its credit, the film also spent a significant amount of time interviewing people who actually use the buildings featured in the documentary, something which sets it apart from the others.

Blair’s film is different from these precedents. In the main, it’s not even really about Parry himself, even as he features in much of the film. It is, as the opening sequence makes plain, about architecture explored through Parry’s design process.

It is not, however, about mere building, which some of the interlocutors were at pains to point out early in the film, a lazy distinction that I have long found inadequate. In this respect, Parry’s work is perhaps the exception that (dis)proves the rule, a series of highly successful, commercially viable buildings that are also considered Architecture.

The film features two of the practice’s current projects: Salisbury Square, currently under construction on Fleet Street in the City of London, and the development of a new mental health hospital, medical research centre, and graduate college at Warneford Park in Oxford, which has recently been submitted for planning and listed building consent.

Time is a lens through which to understand both projects; at Salisbury Square, the design life of the development is 125 years. This is perhaps unsurprising as a public building commissioned by the City itself which accommodates new law courts and premises for the City of London Police.

In this, however, it replaces and consolidates former properties including the purpose-built McMorran and Whitby designed Grade II* Listed Wood Street Police Station, which is itself only 60 years old and has been standing empty for near on a decade.

The reason why this is relevant is the clear anxiety which comes across in the film about the level of demolition, of perhaps unremarkable but nonetheless serviceable office buildings, and the associated carbon cost required to create this new urban quarter, which includes the buildings that Parry and his team have designed.

Parry’s approach has been to contextualise the development around views of the nearby St Bride’s church, itself rebuilt following significant wartime damage, which, along with the design life, suggests a desire to invest the new development with a deep sense of its place in the ongoing development of the City of London. What the development shows, paradoxically, is how temporary this can in fact be for a building, whatever the cause of its destruction.

There is an irony in the self-effacing manner in which the documentary approaches its subject, reflecting Parry’s own modesty, even as he becomes the focus of the film

This preoccupation shapes the approach to the redevelopment of Warneford Park in Oxford in different ways. The Grade II listed building, purpose-built as an asylum between 1821 and 1826 and extended twice later in the 19th century, will be converted to accommodation, teaching facilities and management space, while a new low-rise hospital and research facility will be built within its curtilage.

Here, though, the existing (admittedly listed) buildings will be retained and repurposed and the new extensions carefully integrated in a campus-style masterplan which respects the heritage of the site and the long views to and from the historic centre of Oxford.

There is an irony in the self-effacing manner in which the documentary approaches its subject, reflecting Parry’s own modesty, even as he becomes the focus of the film. This may provide some insight into a documentary which relishes the opportunity to discuss an obviously important subject, while also seeming slightly embarrassed by the attention.

The proverbial notion of time as a great leveller is helpful here. It is the thing that reveals the relative importance of any given site or building, something that no practitioner can claim for themselves or their work, and something which the film acknowledges by resolutely avoiding judgement on Parry’s work.

It also exposes the frailty of the architectural endeavour: however serious the intentions with which you set out, as an architect you do not get to decide how others will view or value your contribution in generations to come, or indeed how long it will endure.

Postscript

Directed by Jon Blair, The Art of Architecture premiered at BAFTA 195 Piccadilly on 17 July, with further screenings planned for the autumn.

Nicholas de Klerk is an associate partner and head of hospitality at Purcell Architecture.

1 Readers' comment