Amin Taha dissects the latest edition of Five Critical Essays, weighing the value of intellectual dissent against the blind spots of culture-war rhetoric

For those of you who don’t know Austin Williams, here’s why you should: He’s that rare thing – an architect, teacher, journalist, author and activist – who, for decades, has relentlessly questioned and tested us, often with contrarian arguments.

Future Cities is one such vehicle, alongside Bookshop Barnies, the Academy of Ideas, and mantownhuman. The latter’s 2005 manifesto unashamedly prioritised people, the Enlightenment, internationalism, and our collective progress, a stance that prefigured later critiques of the emerging degrowth discourse.

It was launched not in a quiet bookshop corner but with a loud party in a disused transformer station. Austin and his co-protagonists were each spot-lit for long enough to shout out one part of their 43-point plan, showering us with polemic and bold red mecha-font pamphlets.

Was it a happening? A Russian Constructivist or Bauhaus political klaxon come to life? Whatever it was, it was theatre, intended to rouse attendees to debate. Which they did, though possibly more on the choreography of the performance than the message.

As a schoolboy, he might have been seen as restless or rebellious, quick to disrupt but quicker still to question. His behaviour in class, though, would have come not from mischief, but from boredom and frustration with received wisdom, spoon-fed without critical balance. His gang, Alastair Donald, Tim Abrahams and now Dame Clare Fox, continue to organise annual debates at the Battle of Ideas and support publications such as Machine Books, still wanting to, in their own words, “shake things up”.

If Austin’s co-provocateur Patrik Schumacher thumps the lectern and keyboard, demanding that a laissez-faire economy allows Hyde Park to become a Manhattan of micro-flats to solve the housing crisis, it’s not because he necessarily believes it. Rather, he appreciates how even flawed polemics, with attention-grabbing rhetoric, can concentrate the mind on more credible alternatives.

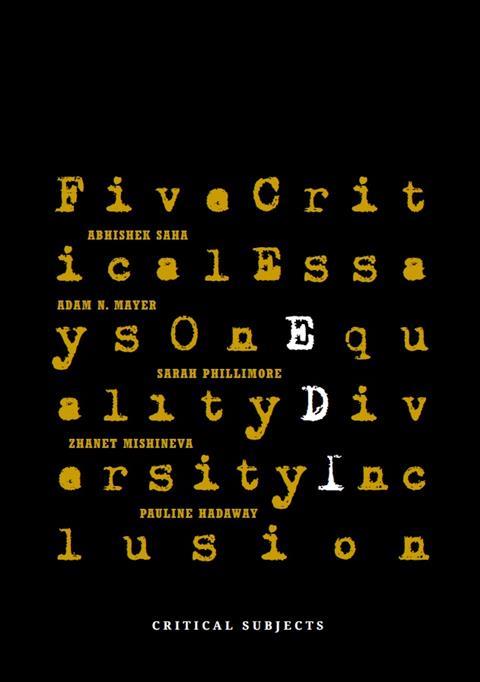

In that context, the sixth edition of Five Critical Essays has Austin kicking the equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) football via US vice-president JD Vance and Elon Musk’s department of government efficiency (DOGE) before passing to Abhishek Saha for the first essay. Are you ready to play?

Saha, professor of mathematics at Queen Mary University of London, persuasively outlines how postwar anti-discrimination laws have evolved from tackling actual discrimination to inferred bias, and now to unconscious bias and the need for safe spaces. He argues that this has led to the rise of institutional structures, most notably in higher education, that waste resources and distort academic agendas while causing the institutions themselves to lose sight of their original intellectual foundations.

To ignore or fall foul of this system, he suggests, is now an existential threat to intellectual freedom.

It is hard to imagine a more counterproductive example for a case about restoring ‘merit and intellectual diversity free from ideological tests’

Saha cites Nathan Cofnas, who was dismissed from Emmanuel College, Cambridge in 2024, as one such example of the risks posed to intellectual freedom. Cofnas, who describes himself as a “race realist”, has argued that different races have “innate psychological traits” and that racial disparities in academic achievement reflect biological difference rather than structural inequality.

That Saha chooses to invoke Cofnas as a victim of ideological censorship is curious, not least because Cofnas’ views – far from being defensible academic heterodoxy – are widely regarded as pseudoscientific and racist. It is hard to imagine a more counterproductive example for a case about restoring “merit and intellectual diversity free from ideological tests”, the solution Saha proposes.

Both Saha and Cofnas were born outside the UK and may not have experienced the country during periods when violent and overt racism was more common than today. While such incidents have not disappeared, many under 30 would struggle to imagine the level of hostility that was previously widespread.

The colour of your skin or wearing religious dress could see you spat at in the street, refused service or attacked. Children could be bullied daily at school, and adults faced exclusion from jobs or housing. If you resisted, you were often blamed and sometimes criminalised. This is the social reality that racial equality legislation sought to address, and any discussion of ideological bias in anti-discrimination policy should begin with that historical context.

In the second essay, the classically-influenced American architect Adam N Mayer picks up the EDI football and goes for a full-body barge into the American Institute of Architects for promoting EDI over Vitruvius’s “strength, utility and beauty”. Why has this happened? Because Modernism’s failed tabula rasa, Mayer argues, let in a cynical postmodernism and deconstructivism that rejects the proletariat through relativism.

Architects, he says, have further distanced themselves from public concerns with, for instance, “gender studies in architecture” and Harvard architecture students voting to divest investments related to the subjugation of Palestinians.

>> Also read: Why architects must confront the changing political landscape

>> Also read: Architecture and the ethics of harm: design, responsibility, and the cost of inaction

Donald Trump’s presidential order that all federal buildings should “respect regional, traditional and classical architectural heritage” is seen by Mayer as a corrective: a way to reconnect architects with an appreciative public. This logical journey is not new and already well countered.

The shortcut to its flaw lies in our forgetfulness. All historical periods include mass building stock, whose visual style is too easily conflated with the politics of the time by a succeeding generation, instead of being seen for what it often is: cheap, expedient and ultimately replaceable.

I empathise with Mayer, as I dare say his thoughts are as redundant as mine when I lecture students on “style wars”. The generation succeeding ours, thankfully, has only academic or ironic interest in styles as dogma.

Unlike Mayer, they see past Trump’s interest in architectural styles. They are instead repulsed by his arm and voice contortions imitating a disabled journalist who had the temerity to criticise him. Ethics, with a respect for all, is integral to their learning and practice. That foundation was laid, in large part, by the EDI policies Mayer criticises.

The ball is then dribbled to Sarah Phillimore, a barrister and co-founder of Fair Cop, which campaigns against “police attempts to criminalise people for expressing opinions that don’t contravene any laws”. She picks up the pace, rewriting EDI as “evasive discriminatory imposition”. She celebrates Trump’s election and, presumably, Musk’s DOGE for bursting the $23.4bn cost we are told stems from postmodernism and queer theory.

Badenoch’s populist stance functions as a dog whistle, suggesting either political naivety or a calculated cynicism

If that hasn’t told us where we are on this pitch, Phillimore explains how what she sees as the subversive goal of pro-EDI activists consists of three parts: “corroding the rule of law”, “rage, rage” and “end compelled speech”. Trump is then given a rest and replaced with Kemi Badenoch, who claims that “positive discrimination harms UK businesses”.

Badenoch’s populist stance functions as a dog whistle, suggesting either political naivety or a calculated cynicism aimed at winning back voters lost to Reform.

Called to the Bar one year before the Disability Discrimination Act became law in the UK, and five years after the equivalent Americans with Disabilities Act in the US, Phillimore may have missed the years of sometimes violent protest and arrest that led to these pieces of legislation. She apparently also missed the debates at the time suggesting that the country would be bankrupted by the introduction of dropped kerbs, ramps and lifts everywhere. It wasn’t.

Nor did listed buildings and whole streets get despoiled by kilometres of ramps. A whole section of the population can now travel further than their front doors, visibly become part of the wider community, join the workforce, and use the same transport, shops, cinemas and theatres.

Some people from “non-white” backgrounds may share Phillimore’s frustration with what she calls “compelled speech”, particularly when well-meaning institutional policies rely on rigid or overgeneralised categories. For example, diversity surveys often expand to include more ethnic subgroups, especially for those of mixed heritage, but still fail to reflect the full complexity of individual identity. There will never be a tick box for “of North-west Middle-East and East-African parentage”.

Phillimore, however, misses the point. The issue is not the intent behind these efforts but their lack of precision. A better approach would be colour-blind tracking of social mobility that still accounts for ethnicity, offering a more accurate picture of both class and racial disadvantage.

And yet, despite these risks, over a century of evolving laws and directives has brought meaningful progress for women, ethnic minorities, disabled people and sexually diverse communities

The fourth essay, by architect Zhanet Mishineva, kicks and stumbles into Mayer’s “style” conundrum, unintentionally concluding the first paragraph with the words now famous as an “X” meme: “Why don’t we have craftsmen that can build like that anymore?”

Her answer: too many new building regulations and codes. And, of course, EDI, which has apparently led them to down tools and give up their highly trained means of living.

The remainder of Mishineva’s essay continues where Phillimore left off, arguing that the taxonomising of social groups can have unintended consequences. By assigning fixed labels, she argues, institutions risk reinforcing narrow, self-limiting definitions of identity which promote conformity to expected cultural norms and create space for pseudoscientific ideas like “innate race trait distribution” to re-emerge.

And yet, despite these risks, over a century of evolving laws and directives has brought meaningful progress for women, ethnic minorities, disabled people and sexually diverse communities. However, progress on socio-economic inequality has been far slower, regardless of ethnicity. And one factor still largely missing from the conversation is age.

Pauline Hadaway, a writer and co-founder of the Liverpool Salon, contributes the fifth and final essay, which offers a more measured but pointed critique of how arts policy has evolved under pressure from both technocratic governance and identity-based inclusion agendas. She traces what she sees as the pendulum swings from postwar universalist ideals, through decades of austerity and managerialism, to a present where institutions struggle with both relevance and reach.

Hadaway focuses on Arts Council England’s EDI strategy, particularly its goal of broadening participation and diversifying leadership by targeting historically under-represented groups. While acknowledging the good intentions behind these policies, she questions whether they are delivering meaningful change.

Drawing on the Arts Council’s own data, she notes that progress has been modest and uneven, particularly in leadership roles, and argues that the emphasis on identity categories may in fact be reinforcing structural inequalities rather than dismantling them.

If you have money, it confirms your status, shields you from most forms of discrimination, and gives you opportunities you can afford to risk

People from affluent middle-class backgrounds still outnumber those from disadvantaged backgrounds in the arts by roughly three to one. For Hadaway, this underscores a deeper problem. She suggests that while diversity policies may change the optics of representation, they too often do little to challenge the social and economic systems that continue to favour the well-connected and well-resourced.

She sees this shift from class-based equity to identity-based inclusion as symptomatic of a broader political realignment that has moved the arts away from their postwar mission of universal access. The result is a sector increasingly out of touch with the working-class communities it claims to serve, reliant on business-style management structures and beholden to shifting political agendas.

The inclusion of under-represented identities, she argues, risks becoming symbolic if it is not matched by efforts to address the entrenched economic inequalities that underpin exclusion in the first place.

Hadaway is sceptical that either the so-called war on woke or more intensive EDI compliance will solve this impasse. Instead, she calls for a deeper rethinking of how public funding is used and for a renewed commitment to the arts as a civic good, rather than a tool of governance or identity management.

And there is the crux. If you have money, it confirms your status, shields you from most forms of discrimination, and gives you opportunities you can afford to risk. The principle of equal rights, intended to enable the full inclusion of society’s diverse spectrum, has always faced resistance, primarily on economic and at times on moral grounds. That resistance only deepens when growing economic inequality is combined with declining social mobility.

This is the condition foreseen by Michael Young in The Rise of the Meritocracy (1958), where an old aristocracy is replaced by a new, self-justifying merit-reward class. This class cannot allow its children to slip down the social ladder and so expends its social and financial capital to secure their position.

It fosters a trickle-down protectionism of privilege, one that resists any intervention perceived as state-sponsored mobility for selectively defined communities, distinguished by skin colour, disability or sexuality, rather than by class.

If we don’t have the clarity to recognise these as socioeconomic problems and problems of opportunity, we cannot change the structure but will find ourselves distracted by dog whistles. Hats off to Williams for taking on a current political lightning rod by including a diverse spectrum of writers and giving each equal space on his platform for us to agree, disagree and develop the argument further.

>> Also read: Inclusion Emergency: ‘An emergency that we can no longer afford to ignore’

>> Also read: Why building inclusion should be seen as a professional obligation

Postscript

Five Critical Essays is published by TRG Publishing.

No comments yet