Horizon Youth Zone has just opened in a refurbished warehouse in Grimsby – one of a flurry of youth centres to have completed in the past three years in disadvantaged areas. As the government promises a £500m investment in youth services, Debika Ray considers the importance of creating civic buildings for young people

“It feels incredible – years of work finally complete,” says Bailey Thomas, a member of Beyond Collective, a group of young people who were instrumental in the development of Horizon Youth Zone in Grimsby, which opened its doors on 14 February. Here is his initial review of this 21st-century youth centre: “It’s full of life and has the perfect balance of calm and entertainment. The colours are beautiful.”

“We have never had anything of this scale purely for young people in Grimsby,” observes Lucy Ottewell-Key, the centre’s chief executive. She is hopeful that its impact will extend beyond its walls and users to the former fishing and industrial town, which has been in economic decline for decades – with low earnings and high crime levels – but with a town centre that is showing green shoots of regeneration.

“It’s on a stretch of the River Freshney that has been derelict for years, so it will give local people pride. It is also bringing more than 60 new jobs to the area.”

The scale and bold positioning is deliberate. “It reflects the ambitious facilities inside, but also means it has a presence,” says its architect John Puttick. ‘We asked ourselves: how do you make sure it feels important and that young people know it is theirs – without mimicking a town hall or patronising them with a wacky design or cheesy colours.”

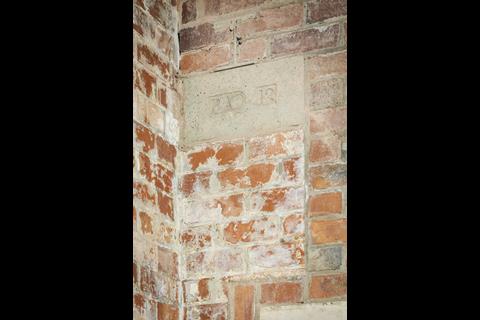

The building sits in the centre of town in a set of refurbished former Victorian warehouses and a 1,115 square metre new-build extension. Arriving via a pedestrian bridge across the water, you are greeted by an L-shaped, brick-clad, slate-roofed building topped with a saw-toothed roof and metal-mesh structure.

Inside is a triple-height atrium, and a range of spaces for activity and mingling – a café, studios for art and craft, a climbing wall, sports hall and performance spaces. Rooms are designed to flow into one another without much guidance and to tempt users to try new things. As well as larger open spaces, there are also intimate ones which cater to a variety of personalities, sensory needs and abilities.

It is one of a series of youth centres that Puttick has worked on with OnSide, the charity that developed the Grimsby facility. In 2019, the studio completed one in Croydon. Later this year, another will open in Preston, as part of the renovation of the city’s iconic brutalist bus station – a bold new entrance with yellow columns and deep overhand announces the presence of the new centre, while also create public spaces to shelter and cluster. Another youth zone in Essex is in the works.

All these have involved extensive engagement with potential users like Thomas – feedback sessions, model-making workshops, and forums where they generate images using AI to debate the suitability of different ideas.

Youth clubs can support young people to become confident, ambitious, interested, try out new things, make friends and have fun – and the architecture needs to enable that

Lucy Ottewell-Key, chief executive, Horizon Youth Zone

It has been a lesson for Puttick too, in designing civic buildings for young people – a task, he says, demands that you leave your architectural predilections at the door. “You have to deliver projects for tight budgets and use robust materials that might not necessarily be your first choice,” he advises other architects. Get it right and such buildings can change lives.

“Youth clubs can support young people to become confident, ambitious, interested, try out new things, make friends and have fun – and the architecture needs to enable that,” says Ottewell-Key.

The Horizon project is among a flurry of youth centres that have cropped up in recent years. Many others have been the result of the previous government’s Youth Investment Fund, which made £300m available to upgrade youth centres in disadvantaged areas of England between 2022 and 2025.

It attracted more than 1,000 applications from local authorities, charities and social enterprises – ranging from ambitious new-builds, to conversions, to off-site prefabricated structures.

“It has been the biggest investment in that youth sector estate for about half a century,” says Nick Temple, chief executive of Social Investment Business, which distributed the funds. “230 projects have completed, reaching more than 45,000 young people.”

Among these are the Swannery in Bristol, converted from a former pub by Barefoot Architects, Lighthouse Project in an old church in Byker, and a scout hut in Sheffield that won a local architecture award.

Many would say this funding was long overdue. Since the Conservative government imposed austerity in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crash, youth services in England and Wales have been decimated.

According to Emma Warren, author of the 2025 book Up the Youth Club, which chronicles the rise and fall of the sector across the UK and Northern Ireland, there were about 11,000 youth clubs across the UK in 2009 and, before 2010, 40% of young Londoners aged 11 to 16 were attending them every week. Since then, youth services have been slashed by 70% and more than two-thirds of council youth centres have closed, compounding the wider social problems created for young people, families and society more broadly by public sector cuts.

Meanwhile, the creeping privatisation of public space – alongside the escalating cost of living and rising youth unemployment – mean young people have been progressively marginalised in the urban realm.

Could things be changing? In December, the Labour government published a new youth strategy which promises a £500m investment in youth services in England, including building or refurbishing 250 youth centres and launching new 50 new ”Young Futures Hubs” in eight areas across the country. These will bring together a range of essential services to support opportunity and wellbeing, and reduce crime.

If we want young people to connect more in person, we need to have a range of spaces they can safely go to outside school or their home

Lisa Nandy, culture secretary

In her forward to the plan, culture secretary Lisa Nandy articulated many of the concerns that have dominated recent debate about the challenges facing young people today, the first generation to be entirely born into a digital world. “The places and spaces that young people have access to have dwindled over a number of years. As a result, many have retreated into their bedrooms and spend much more time online,” she writes.

“If we want young people to connect more in person, we need to have a range of spaces they can safely go to outside school or their home.”

It is easier said than done. ‘You can open a new space, but to get young people to consistently come through the door takes years to build up,” says Lisa der Weduwe, archive project manager at the Museum of Youth Culture, a new institution designed by Caruso St John architects opening in London this spring.

While architecture is not enough – it’s about long-term programming and maintenance too – spaces for young people that are neither home nor school can be empowering, she says. “It’s about creating a safe, informal environment they feel is their own – where they can follow their interests, have conversations, learn new things, but also just hang out without pressure to do anything and without needing to spend money.”

Horizon Youth Zone Grimsby project team

Architect John Puttick Associates

Client Horizon Youth Zone

Conservation architect Seven Architecture

Structural engineer Ramboll and Craddys

M&E consultant Tace

QS Walker Sime

Project manager Walker Sime

Principal designer Jacob Feasey Associates

Approved building inspector Clarke Banks

Fire consultant Clarke Banks

Main contractor Hobson & Porter

Architect Jayden Ali, founder of JA Projects, echoes this. ‘Having a dedicated space, where young people can be free, is an important signifier to know that there is space in the city for them, he says. “You can’t underestimate that from an emotional and a developmental standpoint.”

He recalls his own early experience of youth centres – his mother was a youth worker – as places that incubated culture: “They were spaces where you could bring your personality and lived experience, and be given permission to take up space.”

In 2022, he worked on Rising Green, a youth hub in an old shop front on a high street in north London’s borough of Haringey. “We had previously done some work for the Greater London Authority, in which we found young people felt most welcome on high streets and in parks – they don’t necessarily feel welcome in institutions or clubs.”

It was essential to have screens in the windows so you can show what’s on offer, so people get over the first barrier and come in

Jayden Ali, founder, JA Projects

With Freehaus acting as lead architect, JA Projects focused on the threshold – collaborating with a group of young people to work out how such spaces can be made as approachable as the places they feel comfortable. “We wanted to bring a bit of the high street into the youth club, and the youth club to the high street. For example, we talked about how it was essential to have screens in the windows so you can show what’s on offer, so people get over the first barrier and come in.”

In designing the galleries and circulation spaces of the upcoming V&A East, whose primary audience is Gen Z aged 16 to 24, he has continued to take inspiration from high streets and parks – in an effort to create a cultural institution that, unlike so many others, feels welcoming to younger people.

The threshold was also a central focus for architect O’DonnellBrown when transforming a tired 1970s community centre into a new home for performing arts and youth development charity Take A Bow in Kilmarnock, East Ayrshire. “We had to change how this building was perceived,” says director Michael Dougall. “We wanted it to be unrecognisable to young people when they came back.’

Their £2.4m refurbishment – funded by a patchwork of public grants – involved extensive repair work and the insertion of practical facilities. But extensive consultation via workshops and social media with local young people, established a real need for more than that if young people were actually going to be inspired to use the space.

This was achieved primarily by opening up the building’s frontage and reimagining it as an outdoor stage flanked by timber colonnades and enhanced by graphic signage, bright colours and lighting. You can now see out from the cafe, and in from the plaza created at the front of the building by moving the carpark behind it. Red paving lead up to the building gives the impression of a red carpet.

“We interviewed many users afterwards, and a lot of them said they could not believe it was the same building.”

Architect Guy Hollaway was struck by this sense of awe himself when he revisited the skatepark his practice Hollaway Studio created in 2022 out of an old carpark in Folkestone, financed by a Kent-based philanthropist . ‘The most joyous thing has been young people taking over the building and using it in a way I never would have predicted – it’s taken on a new life.”

The ground floor has a wall full of skateboards featuring artwork designed by users of the centre, and on weekends this space becomes a nightclub. “It was designed for young people in the heart of town where it’s accessible – somewhere with a sense of community, where they can find autonomy and belonging, and test their limits,” Hollaway says.

It has opened up my eyes to how we can engage with young people and put them in a safe place

Bailey Thomas, a member of Beyond Collective

“The best projects are ones where you have got the marriage of architectural expertise and young people inputting their dreams and vision,” Temple says, reflecting on the range of projects he has witnessed coming to fruition.

It remains to be seen what the impact will be of the next wave of youth centres – whether it can go some way towards supporting Britain’s youth to succeed amid the challenges of today. Ultimately, the benefits of having space to be yourself are also intangible and deeply personal – something best summed up by Bailey Thomas’s reflections on the process of planning the Grimsby youth zone.

“It has changed my whole personality – from my confidence to my social skills. It has opened up my eyes to how we can engage with young people and put them in a safe place.” One can only hope that others have similar experiences.

Through ongoing analysis and expert commentary, Regen Connect highlights the policies, funding streams and local priorities that matter most to the construction and development sector.

This coverage will culminate in a special report to be published at our Building the Future Live Conference in London on 7 October.

How you can get involved:

Throughout the year, our team will be gathering insight from across the sector to inform editorial features, debates and events. We welcome contributions from practitioners who want to share experience or shine a light on emerging trends.

Click here for more on the campaign

Be part of the conversation – contact us to contribute or get involved by emailing our deputy editor at dave.rogers@building.co.uk and to find the campaign on social media follow #regenconnect

No comments yet