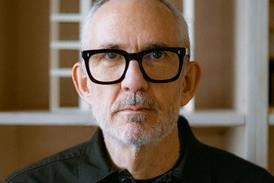

Alex Lynes shares the key questions we need to ask to find out if we’re being greenwashed

Everybody knows that greenwashing is a deadly sin in today’s world, but with every company keen to tell you about how they are going to save us all from climate disaster, how can you spot greenwashing when you see it? We’ve all seen drinks companies advertising plastic bottles that are completely recyclable as if it’s something they’ve just come up with (it’s been their “selling point” for 50 years), yet we still see piles of them in landfills and polluting ecosystems all over the world.

The greenwashed secrets are twofold: firstly, plastic is notoriously difficult to recycle because it is easily contaminated and there are just so many different types to separate. Secondly, it’s all well and good to make something recyclable but if it is not also made from recycled plastic then you’re just pushing the problem on to someone else. If there are limited uses for the recycled plastic, then nobody will bother doing it!

Does it actually add up as a good thing?

As engineers who are often accused of getting bogged down in numbers too easily, we have three simple questions that we ask when presented with a new wonder-product:

- Is what they’re doing just one small part of their business, or a systemwide change?

- Is it actually a change in what they are doing or are they just telling people about it?

- Does it actually add up as a good thing?

Combined, these questions help us not to become over-excited, but the first question is a great initial filter: it’s all well and good to offer a sustainable product, but if it is a tiny part of the business offer or has limited impact, then we have to question whether it’s really going to make a difference.

…lots of companies have realised their product is actually pretty good and started talking very loudly about it

There may be good reasons for this - maybe it’s new or still in development - but aggressively showing it off is misleading. Low-carbon concretes are a great example of this.

Most large concrete companies have a ground-breaking low or zero carbon concrete mix that they promote as proof that you can just keep specifying concrete and rest easy. However, should you try to actually specify this concrete you’ll quickly realise it’s not yet available for purchase or relies heavily on imported steel blast furnace slag (a by-product of a very carbon-intensive industry).

Passing the first question is a great signifier that you’re onto something interesting, but is it actually new? With the rising importance of showing that you’re sustainable or low carbon (not the same thing), lots of companies have realised their product is actually pretty good and started talking very loudly about it. Mineral wool insulation falls into this category – it’s always been a non-combustible “natural” (but heavily processed) product, but those characteristics are suddenly much more important!

Often marketing claims make comparisons to the worst alternative possible or ignore the wider impacts

Even the carbon credentials of mineral wool don’t quite add up. You actually need more mineral wool than higher performing expanded plastic insulation boards – overall it is still better but it’s not the automatic win it claims to be.

Oat milk (and other milk alternatives) are another good example: when did they start proudly boasting they were 70% less carbon? Were they initially targeting that and are they trying to reduce it further? Even if something fails the initial questions here, it’s still very revealing to ask the others.

The third question, ‘does it actually add up as a good thing?’ is the most complex, because it involves actually looking at the numbers: if they’re confusing or not even available, that’s a red flag. Ideally there will be an Environmental Product Declaration to allow for comparison to alternative products or solutions. Often marketing claims make comparisons to the worst alternative possible or ignore the wider impacts.

But what about the other inevitable impacts?

If we consider the current trend for planting trees on the upper floors or façades of buildings, it seems to be a big and positive step that will help to sequester carbon as the trees grow. Standalone it looks like a big win, right?

But what about the other inevitable impacts? Putting trees on buildings requires supporting a large weight high up, which means more support structure and more structure means more embodied carbon.

The regular irrigation requirements also mean larger increased water usage and energy intensive pumping infrastructure. Again, more operational, and embodied carbon.

Life is all about choosing what matters the most to you and checking it’s not doing too much harm to others

When judging the carbon benefits, it’s critical to think holistically about the costs, both financial and environmental. It may be that the ecological benefits of adding biodiverse planting as part of your scheme are most important, and so you minimise the carbon impacts and maximise the different types of plants that can grow as efficiently as possible.

Life is all about choosing what matters the most to you and checking it’s not doing too much harm to others. This last question may be the most tedious to answer but, unfortunately, it’s also the most important.

The power of these questions is their simplicity – they help us avoid wasted time investigating or talking about things that don’t really matter and allow us to spot the obvious marketing ploys with the endless bombardment of ‘disrupting’, ‘breakthrough’, ‘net zero’ claims.

They also force us to think a bit more rationally and get a better understanding of what’s actually being proposed. And if you can’t understand it, it’s probably all just carbon-filled smoke and arrays of mirrors in the desert.

Postscript

Alex Lynes is an associate director at Webb Yates Engineers

4 Readers' comments